Edwards + Johann Blind Date With a Happy Ending 1 + 2 (detail) 2010. Diptych, pigment print on Hanemuehle Photo Rag. Held in both public and private collections

Thieves in the attic

Sally Blundell talks to Edwards + Johann about collaboration, play and process

An unlikely domesticity pervades the small city studio. Drawings and photographed collages are bulldogclipped and hung against the wall. Odd-shaped articles are crammed into stacks of Dole banana boxes. Large cardboard cartons, colour-coded in capital letters – 'BLACK COSTUMES'; 'RED' – are piled up near the ceiling. The props, costumes, photographs and books, the disparate resources that feed into the free-ranging eclecticism that defines the playful, performative and exhaustively explorative collaborations of Edwards + Johann, are boxed up and put away.

Today, I am told, is talking day.

'It's like a dance', says Edwards, 'of research and the making. You are curious, you go off and explore and that feeds back.'

In 2007 artists Ina Johann, born and trained in Germany, and New Zealander Victoria Edwards decided to work on a joint project. The result, Fishing in a Bathtub: Tormenting Luxury (2007–8), is a four-part video, a highly stylised performance piece set largely in an abandoned military outpost on Godley Head, Banks Peninsula. It is eerie and episodic, a series of tableaux and enactments staged by the newly formed Edwards + Johann within a dreamscape of elaborate costumes, minimal props and percussive sounds. Adrift from the usual anchors of story, place and character, it is a mytho-ritualistic performance; arcane, Delphic in its suggested symbolism.

That project, they say, has never stopped.

While they continued to present work as individual artists, they increasingly pooled their years of experience and traditional art school training into a concentrated, methodical, studio-based process of research, debate (more talking days), dress-up (down come the colour-coded boxes) and role play.

'Role play is a big part of our collaboration,' says Edwards. 'That theatrical nature of our process and our work will always come through.'

Over coffee they construct a discursive commentary – agreeing, disagreeing, extrapolating, interrupting – describing, almost enacting, an art-making practice based on a dynamic process of investigation and re-creation.

'It's like a dance', says Edwards, 'of research and the making. You are curious, you go off and explore and that feeds back.'

From every point, agrees Johann 'you venture off again, knowing only that you don't know where it will go.'

Edwards + Johann at Perth Museum and Art Gallery, Scotland 2010. Courtesy of the artists

These extensive periods of experimentation and uninhibited excavation of the art historical, literary and philosophical canons are honed into a careful construction of imaginary landscapes, abstract collages and fictional identities. The result, while still indicative of the formalist parameters of their shared background in printmaking (a process that privileges layering and the controlled interplay of light and dark) is a disparate and free-ranging art practice encompassing video, installation, performance, drawing, frottage, large photographs and tiny, portal-like collages. From this multi-disciplinary practice comes a cavalcade of dislocated figures, disguised characters, strange conjunctions and stranger disjunctions.

As Charles Green, senior lecturer in contemporary art at the University of Melbourne, writes in his discussion on collaborative art, such artists operate as 'thieves in the attic': 'They far from innocently try out different, sometimes almost forgotten identities in the chaotically organized attic of history, rummaging in dusty, dark rooms where variations of authorial identity are stored away from view.'1

On the wall of Edwards + Johann's studio hangs a large photographic portrait of a knight, stiff-backed and cavalier, from the Seven Days and Seven Knights series (2013). A masculine persona, it is complicated by the pink feathery bloom on the shoulder, the op-shop attire in the tradition of objets trouvé, the cut-out hand attached to the body with red string and the pervasive and enigmatic blackness of the background. While alluding to the nineteenth-century tradition of portraiture and the Romantic ideal of the solitary hero, the ambiguous identity of this mock-heroic collation of form and costume – its uncertain gender, its very disconnection from the tradition it emulates – serves as a teasing contradiction to the art historical canon.

Edwards + Johann The Map is Not the Territory—Magenta meets Green 2013. Unique

C-type photographs, partially hand coloured, line drawing. Courtesy of the artists and Nadene Milne Gallery

On another wall a single large photographed rock – grey, pockmarked and detailed – floats on a dense field of orange. One of the seven-strong The Accidental Rebels series (2013), it combines a sense of hurtling force and becalmed expansiveness; a whimsical reading of the strictures of portraiture and a strangely beguiling examination of a common and elemental material.

More usually, however, images of Edwards + Johann, or their fictional identities, are woven into the works. In photographs, drawings, collages and video work they appear as cut outs, flashes of movement, unconventional (and indistinguishable) portraits defined by the hand-fashioned eclecticism of their masquerade. In Self-Portraits: Ausschnitte... I only saw parts of it (2008) and Itching to Futterwack (2009) characters concocted from the Edwards + Johann box of invented personae are defined by the very act of art-making: photographed within or peering over a frame, intruding into or out of cut-out portraits.

Surrealism, wrote André Breton in his Manifesto of Surrealism in 1924, operates 'in the absence of any control exercised by reason, exempt from any aesthetic or moral concern'.2 Edwards + Johann frame this anarchic assault on rationality within a series of disconcerting juxtapositions based on the elaborate artifice of character – often masked, always in costume – that defines oriental theatre, commedia dell'arte and the unruly spontaneity of the carnival.

The results are often unnerving, like a hall of mirrors cracked and warped, or characters from a Fellini film let loose in the world beyond the cinematic set. Photographs of animal-masked figures hang within a staged interior of lamps, rugs and hat stands, their functionality skewed by the displacement of bulbs and outlandishly hand-crafted lightshades. In Skurrile Welten – Strange Worlds (2008) the whimsy of the German phrase is applied to a series of small drawings/ collages – fragments of figuration manipulated and cut into a quixotic world of surreal fairytale, nonsense rhymes, the flashcards of dreams, excavating the line between abstraction and narrative, humour and menace.

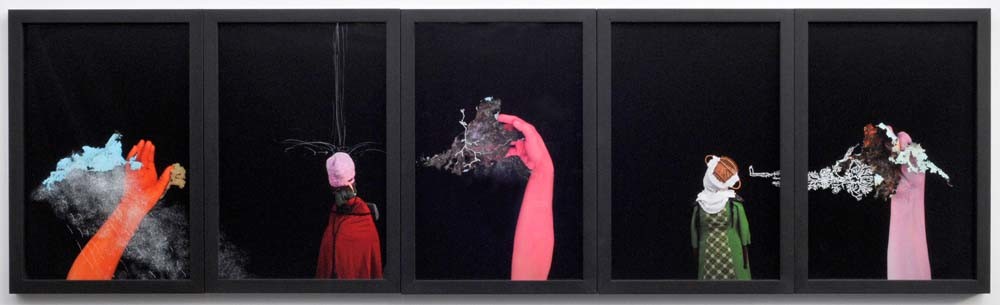

Edwards + Johann On the Seam of Things – Sure to Spill #1–5 2012. C-type photograph, drawing on glass, unique work in five parts. Collection of James Wallace Arts Trust

The connections and collisions that typify these works can be likened to the celebration of chance, accident and improvisation that define the Dada movement, with its rebellious use of collage, assemblage and photomontage. But where Dada emerged as a dynamic response to, and disgust for, the assumed rationality and strategies of civilisation that led to – or at least did not prevent – the atrocities of the First World War, Edwards + Johann present a more art-centric practice: extravagant, self-reflexive and playful.

In the photographic series I'll be your mirror – one of us cannot be wrong (2009) the duo, in outlandish headwear and make-up, occupy a wild, apparently uninhabited and largely unidentifiable coastal landscape. The title perplexes – who is the mirror of whom? Or are the implied reflections to be found in the romantic juxtaposition of character and landscape? And to what extent do we rely on the validation of such reflections to ensure we are 'right'? Such deliberate acts of image-creation, with their surreal, subversive exploration of role and affect, bring to mind the photographic work of Cindy Sherman, in which the camera plays fidelity only to the seamlessly fabricated role play of the artist. Identity is irrelevant; the self deliberately, hermetically, sealed off from the viewer.

At other times such distortions are more subtle. Their video diptych, Revealed by detective work – in search of the possible (2010), the result of Edwards + Johann's residency at the Perth Museum and Art Gallery in Scotland, tracks the flight of a lone gull, its wing tip close to touching its reflection on the surface of a lake, to the beautiful, haunting sound of a Scottish ballad. Or is the reflection bowing its wing to the apparent surface of the water? Which way is up? And how does not knowing impact on the viewer's experience?

This is the realm of ludic play – exploratory, improvisatory, engaging with the social world but operating in a separate, less stable realm of creative misrule; irrational, divorced from concept and theme. In discussing the work of Edwards + Johann, gallerist Robyn Pickens quotes artist Allen Bukoff's description of the DIY aesthetic of the Fluxus movement: 'unfettered play in search of uncharted insights'.

'Play gets to the heart of Edwards + Johann's practice', she writes: 'It is the foundational ground and conceptual space; an enabler, generative. From this act springs a privileging of process and experimentation over any predetermined or finished and final product and opens up their practice to include a performative aspect, theatre, drawing, photography, the body, moving image and installation.'3

Edwards + Johann On the Seam of Things – Days and Knights 3 and 4 2013. Painting and drawing on glass over mixed media work on paper, unique diptych. Courtesy of the artists and Nadene Milne Gallery

For Edwards + Johann the one consistent feature of this space, the one enduring medium, is the process of collaboration itself. Consider the studio as a think tank, says Johann, a research laboratory: 'Someone locks the door and we are in that space together and we come up with what we come up with and we push and pull and something will come out of that.'

While collaboration has long been understood in terms of film, theatre, music and dance, the idea of the artist, the reclusive and self-sufficient genius finding inspiration from a singular private source, has persisted. It is, of course, a flawed image. There is a long tradition of artists' workshops and studios in which art was produced, albeit under the name of a single master. There were, too, the intense social environs of the Montmartre cafés (the Impressionists) and Greenwich Village (the Abstract Expressionists). Avant-garde practice in Futurism and Dada drew on models of collaboration from music, theatre and dance, but within the visual arts the expectation of a single origin of innovation persisted. When the notion of collaboration did appear it quickly became associated with the collective activities of participatory art, in line with Nicolas Bourriaud's definition of relational aesthetics – interactional, socially engaging projects that blur, or make redundant, the very idea of authorship and the individualistic aspirations of so-called 'gallery art'.

From the early 1970s, however, a number of art collaborations, double acts often involving siblingsor partners, began to appear: Pierre et Gilles, Gilbertand George, Eva and Adele, McDermott & McGough,Elmgreen and Dragset, robbinschilds. Most pertinent to Edwards + Johann, perhaps, is the work of Swiss duo David Weiss and the late Peter Fischli (Fischli/Weiss) whose work – a curious, captivating and incongruous practice encompassing film, photography, books, sculptures and multimedia installations – straddles the sublime and the ridiculous, the fantastical and the quotidian.

Such collaborations, writes Green, involve 'a deliberately chosen alteration of artistic identity from individual to composite subjectivity. One expects new understandings of artistic authorship to appear in artistic collaborations, understandings that may or may not be consistent with the artists' solo productions before they take up collaborative projects.'4

As enacted by collaborative duo Marina Abramović and Ulay (performance artists working together between 1976 and 1988) this combined authorship, writes Green, results in a 'third hand', an artist or persona with no real existence outside of these shared endeavours.

Edwards + Johann Looking At – The View 2009. Diptych, pigment print on Hahnemühle Photo Rag, 308gsm. Courtesy of the artists and Nadene Milne Gallery

Sally Blundell is a Christchurch-based freelance journalist.

Rather than presenting a composite of the work of Victoria Edwards and Ina Johann, the Edwards + Johann practice involves the construct of such a new hand, an 'energy field', says Edwards, existing above and beyond the two artists, an alliance in which the surreal nature of the work and the process of art-making form a new working space, literally and figuratively, where the whole is more than – and separate from – the sum of the parts.

'Each of us is an individual,' says Johann. 'But then there is that new space where we can do things we couldn't do as individuals. We can push each other and nudge each other into this new space.'

People are puzzled by it, she concedes.

'It flies in the face of the idea of the one genius artist with one voice and building a reputation based on that. But this isn't about ownership and authorship, it's not about us individually, it's not about controlling, it's not about the ego. That sort of me-ness gets in the way.'

'It's about process,' says Edwards. 'We are two individuals but there is this third hybrid space where things form.'