Trouble ahead: Roger Boyce and The Illustrated History of Painting

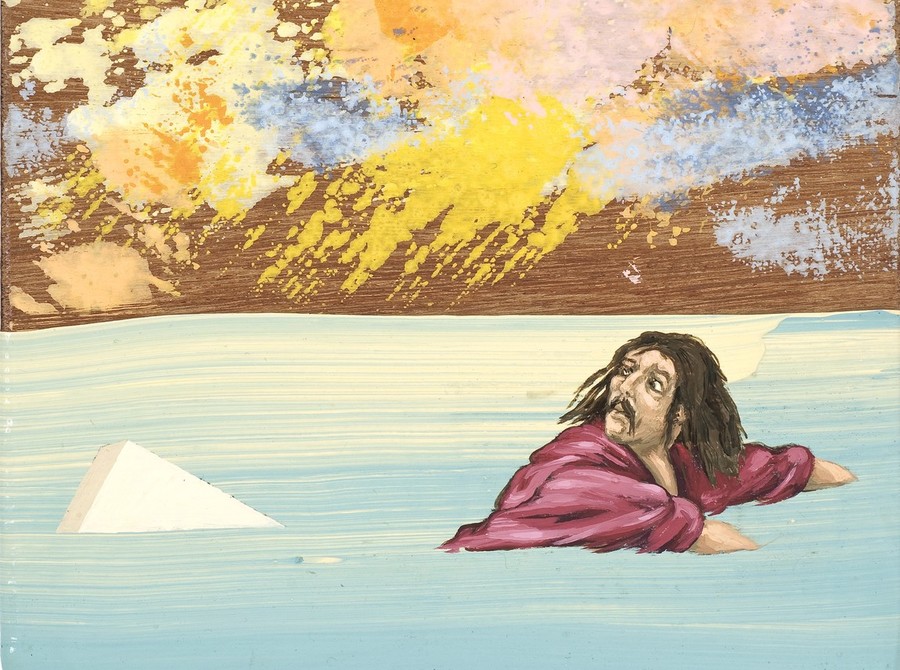

Roger Boyce Great White (detail) 2008–10. Oil and water-based mediums on hardwood ply. Reproduced courtesy of the artist, Brooke Gifford Gallery, Christchurch and Suite, Wellington

If you want to get some perspective on the art of today, a good but grim way of doing so is to imagine it from the future's point of view. When the archaeologists of the year 2195 pick their way across the ruins of the city of Christchurch, what traces of art and culture will they find amongst the rubble? And more to the point, what fragments would we want them to find-if we had the choice?

In the upbeat version of this future fantasy, the archaeologists strike it lucky. Clambering across the remains of the city's one-time centre of learning, the University of Canterbury Library, they discover a dusty recess half-hidden beneath a slab of brutalist concrete. Inside, miraculously preserved from flood and fire, there's a stash of precious art books. Ernst Gombrich's The Story of Art, H.H. Arnasson's History of Modern Art, perhaps even Michael Dunn's New Zealand Painting: A Concise History. Histories of the art we judged great and good, packed with pictures we thought mattered.

If the future's approval is what we're after, then no doubt this discovery is the one to wish for. But I can't help imagining a slightly different discovery – one with funnier and more confusing results. In this alternative scenario, the archaeologists unwittingly begin digging for samples in what was once the University's School of Fine Arts. And there, sealed in a box amidst the wreckage of a lecturer's office, they discover a much stranger account of art-making in our time-namely Christchurch painter Roger Boyce's The Illustrated History of Painting.

I don't mean to dismiss the noble Gombrich and Arnasson, or to make light of the scary fate that many commentators predict for our cities; it's simply fun to imagine the trouble Boyce's Illustrated History might cause for any would-be reconstructor of our historical moment. Most histories of painting play out as a sequence of movements and styles, with one ‘ism' giving way to the next in a soothing and logical rhythm. But Boyce's version is about as soothing as a lawnmower on a suburban Sunday morning. Across a hundred lusciously painted and mischievously detailed panels, Boyce reimagines the history of his medium as a succession of creative mishaps, ludicrous stunts, and preposterous endeavours. Instead of heroically ‘breaking through' and ‘leading the way' as painters are supposed to do, Boyce's painters slam into their own limitations like pratfalling comedians in a knockabout farce.

The cartoon look and low humour of Boyce's Illustrated History may seem out of keeping with his serious-sounding role as senior lecturer in painting at the University of Canterbury School of Fine Arts, but it's significant that Boyce is a teacher. His Illustrated History reminds me of a distinctive teaching aid Boyce brought with him when he came to Christchurch from the States six years ago – nine slide carousels brimming with reproductions of paintings, from prehistoric through to postmodern. With this battery of images, Boyce wasn't out to tell his students a traditional history. Instead the aim was to soak them in the sheer range of possibilities for painting today, and thus raise an unsettling question: in an artworld where anything is possible, where all history is up for grabs and reachable at the click of a mouse, how does one choose what kind of painter to be? How to wade through the length and depth of painting's past and emerge without feeling terminally exhausted or bewildered?

I like to think of the Illustrated History as Boyce's wayward answer to his own question – a gonzo variation on the ‘allegories of painting' created by high-minded academicians in centuries past. From the opening title page right through to the final panel with its blunt conclusion (Ends), the panels offer funny and ever more frenetic propositions about what a painter is. The painter as a high-diver leaping into the whiteness of the canvas below (Yves). Or as a boxer sucker-punched by his own painting (KO). Or as a saint bleeding paint from his wounds (Stigmata). Strivers, doofuses, flame-outs and fools, Boyce's little artist stand-ins struggle to make their mark on art's history, to prove their mastery of the medium. But time after time they find themselves undone by their own ambitions-weighed down by the tools of the trade (Burden of dreams), washed up by waves of art history (Washed up), or stuck in traps of their own creation (White man's burden).

Taken individually, the paintings exude a fierce, almost fatalistic humour, with Boyce running a satirist's skewer through every creative myth and painterly cliché he can see. But the more I see of the series (there are eighteen paintings still to go at the time of writing), the less it feels like a straight-out satire at painting's expense. For a start, you can't miss the care Boyce has lavished on each panel, rendering his scenarios with a devotional intensity that recalls medieval illuminations as much as it does Mad magazine. But even more compelling is the sense of momentum – of sheer freewheeling enjoyment-that accumulates throughout the series, an enjoyment that competes with and increasingly overrides the satirical point of individual paintings. Like the best satirists, Boyce is clearly in love with the very things that vex him, and he goes at the problems of painting with the headlong gusto of a stand-up comic who has at last found a topic large and annoying enough to take all the spleen he can spray at it.

Boyce didn't set out to paint a hundred paintings. The series began in a what-the-hell spirit with the painting of some bright but bleak little scenes on scraps of plywood that had been lying around the studio. Portraying a series of artist suicides-painters ‘offing themselves' (Boyce's phrase) by means of rope, gun, fire and more-these early paintings are intensely, you might even say passionately, negative. Painting is finished, these works seem to say, and the painter is at the end of his rope. But having begun in this bleak and final spirit, it's as if Boyce found himself intrigued and, with each new work, increasingly carried away by the very medium whose death he was preparing to announce. In other words, he found himself in the same position as the little painters he portrays – toiling away inside painting's history with a mixture of hope, desperation, energy and glee.

Even as it lets the air out art's highest hopes and ambitions, The Illustrated History of Painting is a work of serious comic ambition. Let's hope the archaeologists of 2195 see the funny side.

Justin Paton

Senior curator