Ricky Swallow

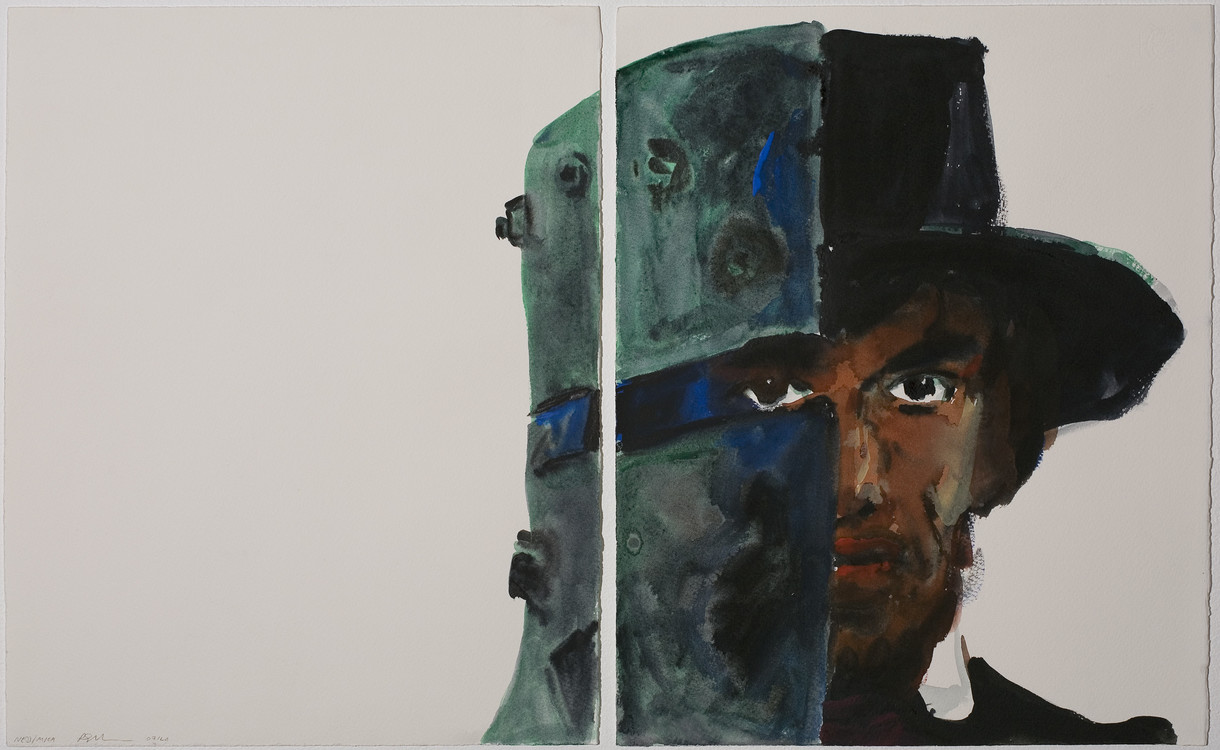

Ricky Swallow Ned/Mick 2007. Watercolour on paper. Proclaim Collection, Melbourne. Reproduced courtesy of the artist, Darren Knight Gallery, Sydney, Stuart Shave/Modern Art, London, Marc Foxx Gallery, Los Angeles, and Hamish McKay Gallery, Wellington

Ricky Swallow is one of Australia's most renowned artists. As a sculptor he represented Australia at the 2005 Venice Biennale, and many of his carved wooden works are currently the subject of a survey exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne. However, works on paper have always been a part of Swallow's art practice, and a new exhibition at Christchurch Art Gallery brings together a broad range of these playful and atmospheric works. Here senior curator Justin Paton considers Swallow's early interest in evolution and science fiction, and delves into the artist's more recent studies of musicians 'on the edge of dissolution'.

The main actors in Ricky Swallow's early watercolours are intelligent and faintly menacing monkeys. They read books, operate laptops, listen through headphones, pilot spaceships towards other worlds, and generally run the show. Swallow records their actions and antics with all the enthusiasm of a field researcher with notebook flipped open: here they are reading books; there they are fondling guns. It's zoology shaded by comedy, a kind of diary of evolutionary downfall.

However, like William Hogarth's many eighteenth-century paintings and engravings featuring preening and puffed-up monkeys, Swallow's watercolours of this type are not about monkeys at all, but rather us humans. They are about our flailing and preposterous attempts to make progress, get ahead, extend ourselves in space and time. Whether they are tinkering with gadgets, steering spacecraft, spraying graffiti on walls or creating fresh versions of themselves in the lab, Swallow's monkeys might all be considered surrogate artists, using whatever is at their disposal to reach beyond themselves. The resulting watercolours are science fictions of a comic and wistful kind, gently dwelling on the absurdity of our efforts to make ourselves known in a limitless universe.

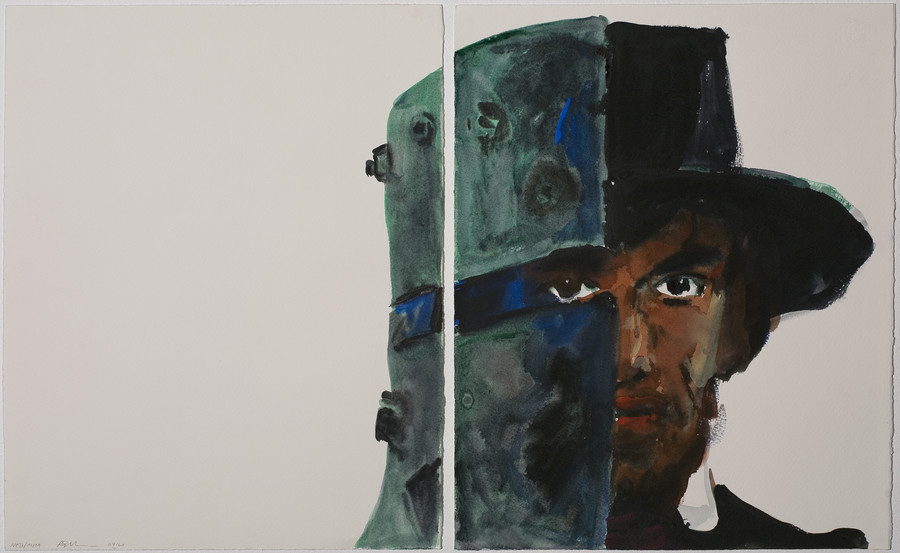

Ricky Swallow When you were gone 2007. Watercolour on paper. Private collection, Melbourne. Reproduced courtesy of the artist, Darren Knight Gallery, Sydney, Stuart Shave/Modern Art, London, Marc Foxx Gallery, Los Angeles, and Hamish McKay Gallery, Wellington

Leaf through Swallow's recent watercolours, however, and the monkeys in their sci-fi settings fade completely from view. In their place come human faces and figures of a much more certain vintage. These watercolours are based on photographs—though 'based' sounds too solid for what happens in them. It is as if each portrait were placed in the opposite of developing fluid, a substance that softens the certainty of the photographic record and takes it to the edge of dissolution. The face seen close up in When you were gone is almost lost in the pooling pigment. The paired faces in False true lovers look at once stunned and accused by our interest in them. The faces of members of the legendary Kelly Gang are rendered in bruised blacks and blues, and look by turns malevolent (Ned), wretched (James Kelly), and too far gone to care (Hanging Joe Byrne). And the same faces receive an unexpected second life in watercolours that portray the outlaw Ned as played by rock star Mick Jagger in the 1970 film Ned Kelly—pop cultural memory bleeding back across colonial history.

Of all the faces Swallow portrays, none haunt his watercolours as persistently as those of musicians. From John Fahey and Nick Drake through to the reedy, melancholy figure of 'Papa John' Phillips, co-writer of California dreamin', musicians form a kind of shadow community within Swallow's art—half-hip and half-haunted, an unlikely aristocracy of shaggy man-boys, wistful skinnies and finger-picking daddy-os.

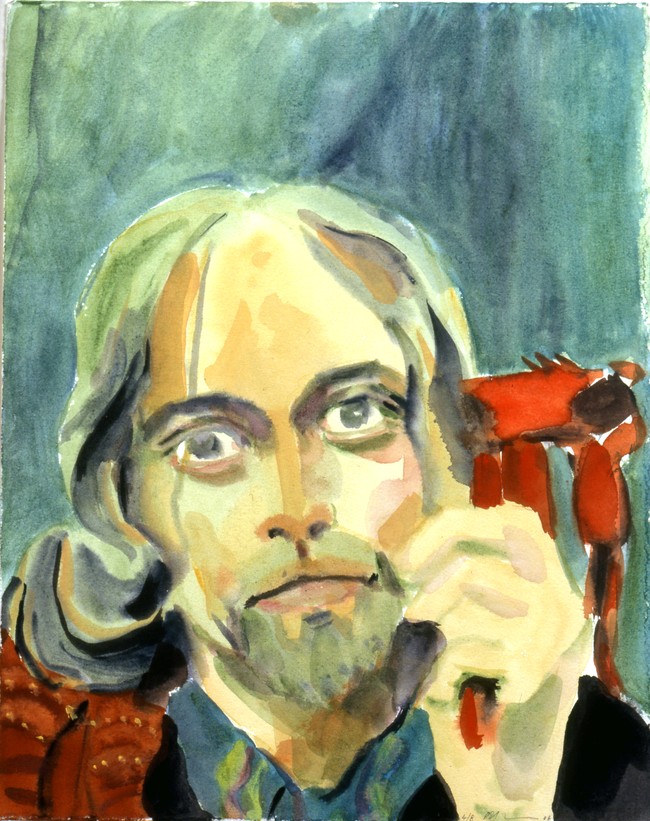

From Ricky Swallow The hangman's beautiful portraits 2006. Watercolour on paper. Burger Collection, Hong Kong. Reproduced courtesy of the artist, Darren Knight Gallery, Sydney, Stuart Shave/Modern Art, London, Marc Foxx Gallery, Los Angeles, and Hamish McKay Gallery, Wellington

Swallow is known to be an obsessive listener, someone whose art is motivated as much by music as by the work of other visual artists. Since moving to Los Angeles he has immersed himself in Californian music of the 1960s and 1970s. On that count, these watercolours might be considered the notes of a fan, Swallow transferring these faces from album covers into the scrapbook of his own enthusiasms. If this is fandom, though, it's fandom of a peculiar kind, tender and yet thoroughly distanced. In the photos that he selects, the musicians adopt the role of reluctant prophets, modern-day troubadours, staring past or through the camera towards some horizon of possibility.

Like Francis Upritchard, Damiano Bertoli and David Noonan, to name just three artists of Swallow's generation who are also reaching into the archive of this period, Swallow seems obscurely attracted to the mixture of hope and melancholy in these images—the way they sit on the fault line between 1960s idealism and the disenchantments of the 1970s. The closer he goes to these faces, the more puzzling their presence becomes. No longer joined together in hippy solidarity, the faces in The hangman's beautiful portraits (based on a photograph of an Incredible String Band album cover) turn solemn, strange and old. The musicians in One nation underground seem to pass from currency before our eyes, presented like fragments peeled from a fan's album, or busts in a museum of antiquities. By turning this period's pop stars into figments and monuments, Swallow does justice to an odd aspect of memory, which is the way faces and events from the recent past often feel further away from us than those from centuries past. We walk through our lives buoyed by the illusion that the crucial details are right there—that we can reach into the filing cabinet of memory and find just what we need. But, as anyone can discover for themselves when rummaging back through old boxes of photos or papers, even your self of five or ten years ago can feel like someone unfamiliar. Thirty-odd years since their heyday, Swallow's musicians waver on the brink of unfamiliarity. They're halfway between going and gone.

So is Swallow farewelling these figures or bringing them back? Reclaiming them or letting them go? In the end I think the watercolours must be counted as acts of commemoration—modest, indistinct and partial, certainly, but commemorative acts nonetheless. The evidence for this lies in the simple fact that he made them in the first place. Having listened to their music and looked at their photos, he set to work with paper and brush. And what led him to do so, I suspect, was not the looking so much as the listening. Songs bring the past vividly into the present because voices are such intimate things. Push play on a recording and the voice of someone long-gone is right there with you all of a sudden. Little wonder that Edison's phonograph recordings were once thought to offer the chance to listen in on the dead.

Justin Paton

Senior curator

This essay is an extract from 'The Weight of Paper', first published in Ricky Swallow: Watercolours, University of Queensland Art Museum, 2009. Ricky Swallow: Watercolours is in Touring Gallery C from 12 December 2009 until 21 February 2010.