B.

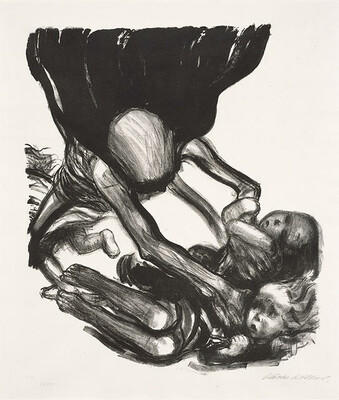

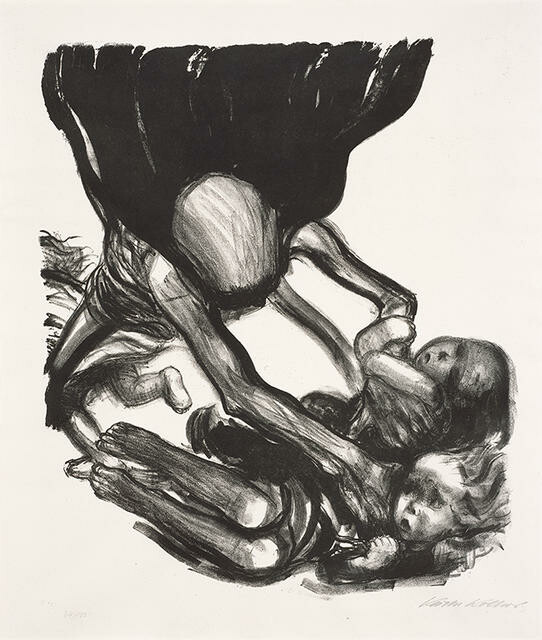

Tod Greift In Kinderschar by Käthe Kollwitz

Collection

This article first appeared as 'A compelling artist-advocate remembered' in The Press, 22 November 2017.

Mothers and children amid poverty and death were German artist Käthe Kollwitz’s constant subjects. Her works demonstrate the powerful capacity for empathy that has led her to be regarded as one of the twentieth century’s most compelling artist-advocates, speaking on behalf of the marginalised and vulnerable. Two world wars—and the devastating social conditions of Germany in the 1920s—gave her ample material.

Kollwitz was born into a middle-class family of nonconformists in Königsberg, Prussia, in 1867. Her parents encouraged her to study art, although German women were not admitted to higher education until 1908. Her early graphic works illustrated revolutionary moments from history and literature. She married a politically committed doctor and moved to Berlin where they lived among his patients. Karl Kollwitz worked for a health insurance company that served the city’s tailors and their families; his medical practice included the densely populated five-storey rental tenements of Prenzlauer Berg, with their dank inner courts and gloomy outlooks. Kollwitz depicted the desperate lives of her husband’s patients in a series of prints concerned with the effects of malnutrition, unemployment and the exploitation of the poor.

Kollwitz’s working-class Berlin is the grim city described in 1939 by Christopher Isherwood in Goodbye to Berlin:

Berlin is a skeleton which aches in the cold: it is my own skeleton aching. I feel in my bones the sharp ache of the frost in the girders of the overhead railway, in the iron-work of balconies, in bridges, tramlines, lamp-standards, latrines. The iron throbs and shrinks, the stone and bricks ache dully, the plaster is numb.

Her own life, though privileged in comparison with the subjects of her work, was marked by tragedy. Her son Peter, who had been the model for studies of the dead child in a well-known early etching, Woman with Dead Child (1903), died on the battlefield in World War I. Her grandson, also named Peter, was killed in action on the Eastern Front in World War II. From the 1920s onwards, her work was increasingly concerned with the dark realities of war, particularly for those left behind on the home front. “I am simply satisfied,” she wrote in 1922, “for my work to have a purpose. I want to be effective in this time in which people are so perplexed and in need of help.”

Christchurch Art Gallery acquired the important print Death Reaches in to a Group of Children in 1988. It’s from Kollwitz’s final lithographic print cycle, in which the personification of death visits the most vulnerable members of society. Sometimes death extends a welcome hand, arriving like an old friend long anticipated; sometimes death comes violently and unexpectedly. The figures are set against blank backgrounds, ungrounded in time or place. With their radical economy of means, her late images speak of a general human condition rather than of specific war histories.

Kollwitz made her Tod (death) series while working among young artists in communal studios in Berlin’s Klosterstrasse. She had been forced to resign from her role as director of graphic arts at the Academy of Arts the previous year when the Nazi Party came to power, after signing a public appeal against fascism. Over the next few years she was prevented from exhibiting her work publicly, and in 1936 was interrogated by the Gestapo and threatened with being sent to a concentration camp. In 1943 she was evacuated to Nordhausen to escape the bombings in Berlin. Her house, and much of her work, including her printing plates, were destroyed in an air raid in November that year. She died aged 77 in 1945, just eight days before Hitler committed suicide in his Berlin bunker. She is commemorated in the names of streets and squares all over Germany.