B.

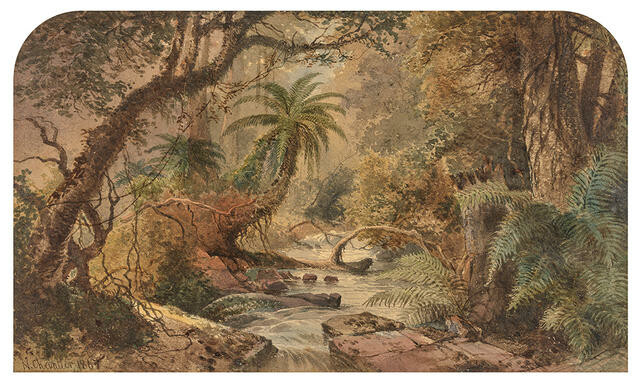

Pigeon Bay Creek, Banks Peninsula, N.Z. by Nicholas Chevalier

Collection

This article first appeared as 'A poignant look at Pigeon Bay's past' in The Press, 14 November 2017.

Nicholas Chevalier’s watercolour of one of the many picturesque bays on Banks Peninsula / Horomaka provides a tantalising glimpse into the past. Painted in 1867, the dense bush we see here that once covered Wakaroa / Pigeon Bay is in stark contrast to the pastoral outlook that confronts visitors today. Pigeon Bay was prized by Māori and Pākehā alike for its safe anchorage, abundance of food and easily accessible timber. It is thought the bay was renamed by whalers for the abundance of kereru in the area.

Having forged a successful career in Melbourne, Chevalier was one of the earliest professional artists to visit Canterbury when he was commissioned in 1865 and 1866 by the Otago and Canterbury Provincial Governments respectively to make sketching tours throughout their regions. Pigeon Bay was a place of respite for Chevalier in between his arduous sketching tours of Otago and Canterbury. He arrived at the Bay in autumn of 1866. His wife, Caroline, was waiting for him, and they stayed with their close friend George Holmes and his wife, whom they had known in Melbourne. Holmes had won the contract to construct the Lyttelton rail tunnel in 1861 and took land at Pigeon Bay as part payment. He was attracted to the bay for its dense forest, the very forest depicted by Chevalier, which he felled and milled for railway sleepers for the tunnel project. Caroline Chevalier kept a diary while at Pigeon Bay. She wrote about “…the immense logs of the majestic totara trees […] Many a fallen giant I counted and measured by my height and six to seven lengths of I suppose 8 feet long and are higher in diameter than I (5ft. 5in.) made the stem of each tree before the branches began. They were magnificent.”

It has been estimated that at one point Banks Peninsula / Horomaka’s native forests were reduced to a mere one per cent of their original coverage as timber was relentlessly felled to make way for pasture. Chevalier’s watercolour is all the more poignant with this in mind, and for me, as well as being a very charming painting of one of my favourite regions, it conjures up an intense sense of loss of the incredible biodiversity that once covered this landscape. Happily, there has been much regeneration over the past three decades most notably the excellent work being done by Hugh Wilson and his volunteers at Hinewai Reserve above Otanerito Bay, a spot that is well worth the visit if you get the chance.