B.

If a tree falls in a forest

Behind the scenes

but a conservation minister doesn't hear it fall, does it make a dollar?

New Zealand's native trees have had a hard time of it over the years. From my kitchen window I look out over Banks Peninsula, which is truly beautiful but as barren as a highland Scottish moor.

Between 1860 and 1900 it's estimated that the Banks Peninsula was stripped of up to 98% of its indigenous forest cover. While rimu is now prized a furniture grade timber, at the time it was primarily used as a cheap framing timber. The beautiful totara, which once made up much of the Peninsula's forest cover, was so rot resistant that its greatest value to colonial settlers seems to have been in fence posts and house pilings of all things. And of course, clear land is farmable. Traces still remain of course – walk from Mount Herbert across towards Akaroa and you'll pass through a veritable Somme of skeletal podocarpus totara. But in between the small pockets of regenerating forest in isolated gullies, there is undoubtedly some excellent grazing...

Since recognition of the perilous state of NZ's remaining native forests and the protection of remaining old growth forests, the perceived and actual value of these timbers has increased massively. The high value of that timber makes high cost/low impact extraction methods financially viable, and the logging of rimu is now managed sustainably (although at up to 450 years from seed to saw, that's a long game to play). Of course recently Christchurch's rampant residential demolition has seen huge quantities of these timbers removed from houses, and organisations like Rekindle (and many others) are admirably harnessing the desire to avoid these irreplaceable materials finding their way into our giant piles of quake waste. Rekindle describe it a constructive response as we remember and rebuild.

So this weekend it's been interesting to see the current move to harvest wind-felled trees from the conservation estate downed by Cyclone Ita being painted in the same positive, feel-good light.

I was absent when we did forest management 101 at school, but statements like 'no good purpose is served by leaving it all to rot' seem to me to display an opportunistic disregard for the way principles under which these protected areas were established. Am I naive to think that the 'good purpose' should be the preservation of a natural cycle, albeit one affected by an unusual weather event. Trees fall. They rot, they turn to mulch, they enrich the soil where more trees grow.

That doesn't turn a buck though...

Why is it suddenly acceptable to remove wind-felled trees for sale, when before Ita, it wasn't? Where is the discussion? It's difficult not to see in this the continuation of an extractive economic policy in which somehow it's okay to enter protected land to reap financial reward and financial gain hugely outweighs ecological impact. But for some reason that doesn't seem to make us angry enough.

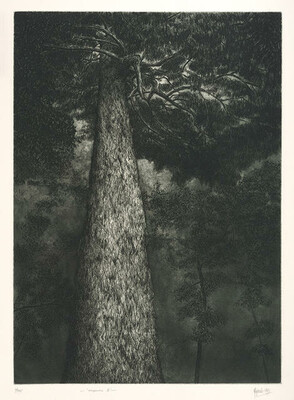

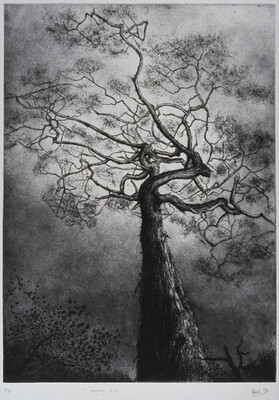

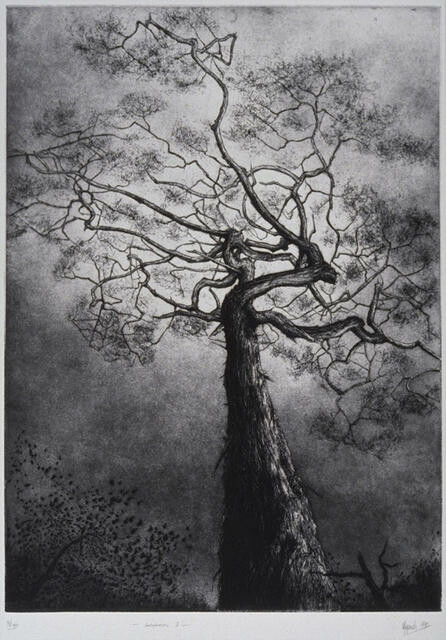

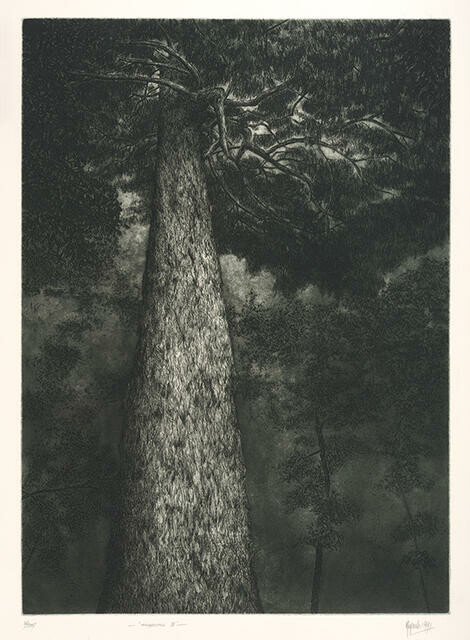

Printmaker Denise Copland has for years used her art to voice her concerns about the destruction of indigenous forests. This series of bleak and imposing etchings from the early 1990s use a move from dark to light to highlight the clearing of New Zealand's irreplaceable forests.

Angry enough to draw? It's a good start.