Kā Kaupapa o te Wā

What’s On

Raymond McIntyre: A Modernist View

Dynamic and progressive paintings and woodcuts from one of Aotearoa’s New Zealand foremost modernist artists.

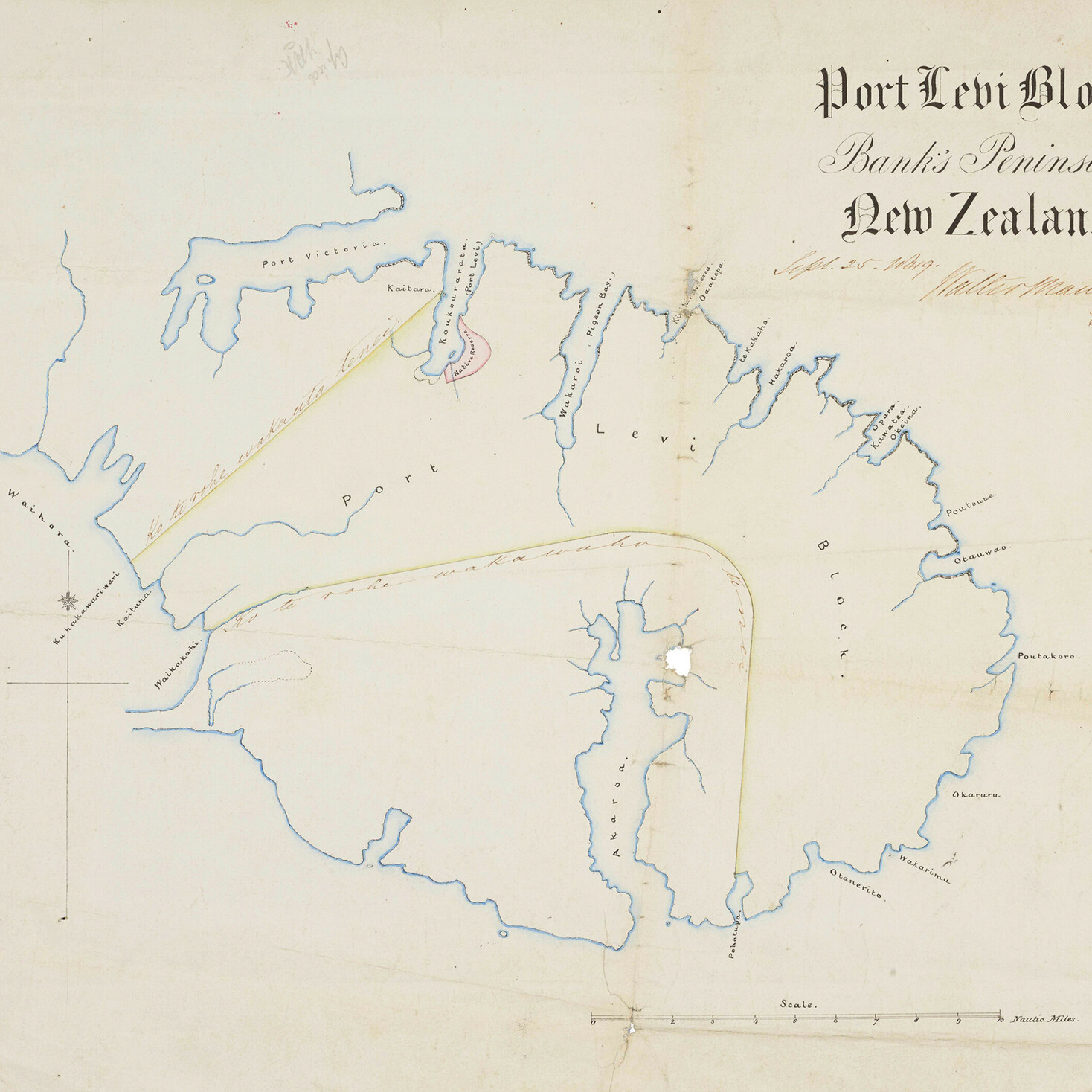

Living Archives

Archives that tell stories about artists and history in Aotearoa

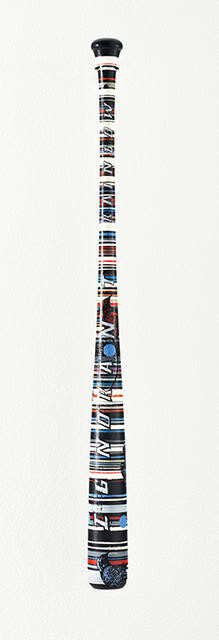

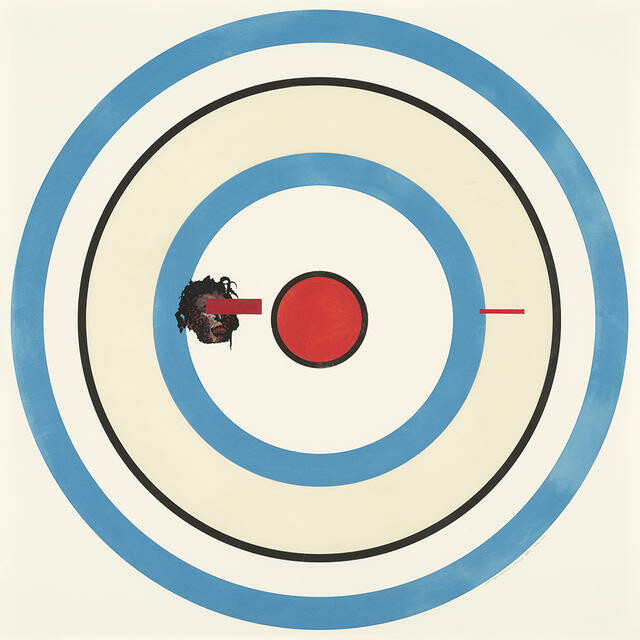

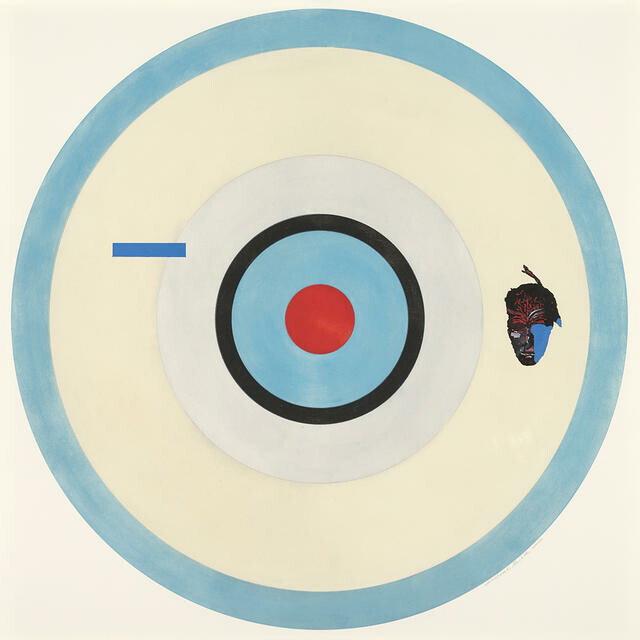

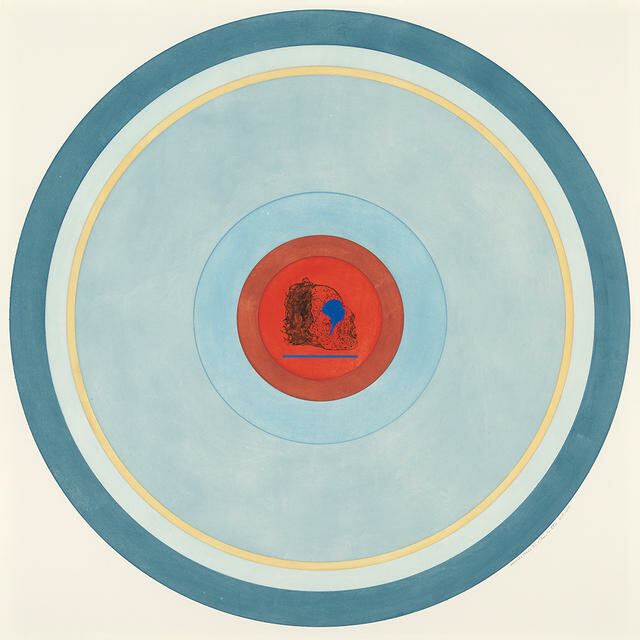

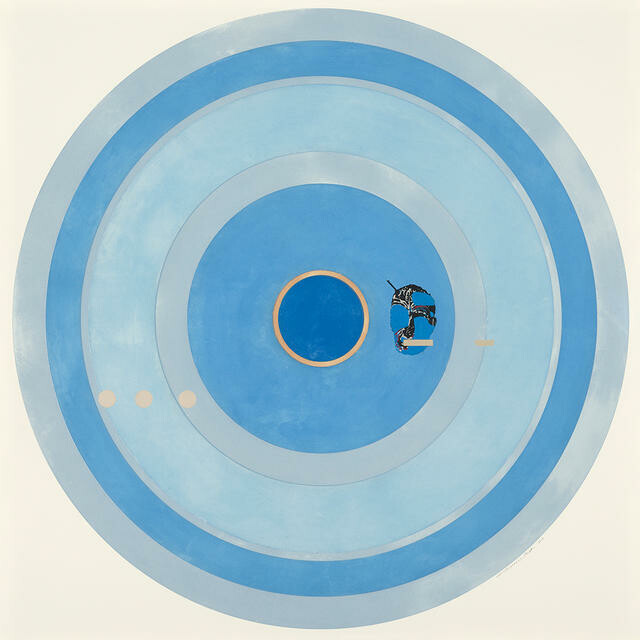

Whāia te Taniwha

Māori artists consider the enduring relevance of taniwha in Aotearoa.

E tuwhera ana te wharetoi i kā rā e 7 o te wiki, 10am - 5pm

Ka tuwhera ki te 9pm i kā pō Wenerei

Open 7 days, 10am - 5pm

Late night Wednesday until 9pm

Uruka utukore, ahokore utukore

Free entry, free wifi