Foreigners Everywhere

Fred Graham at Te Uru

Queen Elizabeth II and the Duke of Edinburgh survey the Karāpiro reservoir from the top of the dam, which flooded Fred Graham’s ancestral papa kainga at Horahora, “UK Royal Family Tour 1953-54”. Auckland War Memorial Museum, neg. S1344. Stuff Limited / Auckland Star Collection

Stranieri Ovunque - Foreigners Everywhere is the title and theme of the International Exhibition curated by Adriano Pedrosa for the sixtieth Venice Biennale. As a necessary condition of such projects, the theme works as a signal, provocation and rationale for the amassing of globally disparate works of art and sets the tone of this highly politicised event. Foreigners Everywhere is a particularly intriguing premise for drawing the work of eight Māori artists into the urgent political concerns currently playing out at the Biennale. While much is being made of this unprecedented situation – and rightly so – the celebrations at home have yet to turn to a critical examination of how the work of these artists operates in that context.

Toi Whakaata/Reflections: Fred Graham at Te Uru Waitākere Contemporary Gallery (08 June – 18 August 2024) seems a world away from the Venice Biennale, though connected by the presence of Sir Fred Graham’s work. Rather than attempting to understand Fred’s contribution to the corpus of the International Exhibition, it appears potentially more productive to apply the concept of Foreigners Everywhere to this select gathering of Fred’s sculptures at home. Indeed, as the title image attests, Fred’s life has required him to come to terms with foreigners everywhere, notwithstanding his experiences of being cast as a foreigner – or stranger – in his land, which are central principles of the International Exhibition concept.1 While ‘foreigners everywhere’ characterises aspects of Fred’s lived experience, his art practice has consistently articulated a fixed notion of belonging to place and significantly contributes to the reclaiming and marking of those spaces. In this way, Fred’s work stands in opposition to Pedrosa’s meta-narrative for the exhibition: ‘that no matter where you find yourself, you are always truly, and deep down inside, a foreigner’.2

Fred’s upbringing is a haunting tale of the legacy of war and colonisation and involves a direct experience of land confiscation – all of which he willingly conveys in a strikingly plain and sober fashion. His Ngāti Koroki Kahukura ancestors established themselves on lands between Maungatautari and the Waikato awa, a diverse and abundant landscape populated with numerous kainga. After the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, the Waikato River highway enabled their crops to be easily transported to Auckland and exported abroad to Australia and the Americas, an example of Māori enterprise replicated throughout the country at this time. Simultaneously, Māori leaders grew alarmed at the high levels of British migration and the Crown’s aggressive land-purchasing strategies and proposed the establishment of a pan-tribal political leadership to provide a united Māori response to these issues. Their initiative led to the coronation of the Waikato-Tainui Arikinui, Pōtatau te Wherowhero, as the first Māori King at Ngaruawahia in 1858.

In 1859, disputed land sales in Taranaki became a cause of grave concern for both Māori leaders and the Government. Armed conflict erupted in 1860, signalling the start of the New Zealand Wars. In 1861, Pōtatau, Ngāti Koroki Kahukura leader, Tioriori, and Ngāti Haua leader, Wiremu Tamehana, travelled to the region to restore peace. However, their anti-land selling position alarmed Government officials, who began to formulate plans to invade the Waikato, depose the King and clear the area for European settlement. Under the premise that the King was preparing to attack Auckland, Crown forces invaded the Waikato in 1863. At the siege of Rangiriri on 20 November 1863, Tioriori was arrested along with 180 others and detained without trial on the hulk Marion anchored in the Manukau Harbour. On 8 December 1863, Crown forces took possession of the King’s pā at Ngaruawahia, and the King went into isolation. Ngāti Koroki Kahukura and Ngāti Haua established a defensive post at Maungatautari as part of a chain of fortified pā along the south-eastern boundary of the Kingitanga territory, a boundary that became known as the aukati. After the battle of Orākau at Kihikihi, Crown forces converged at Maungatautari, determined the area to be impenetrable and moved eastward to Tauranga. The area delineated by the aukati became known as The King’s Country, from which Europeans were prohibited.

The Government then launched a new and unprecedented form of attack. In December 1863, the Government passed the New Zealand Settlements Act, which declared that Māori engaged in rebellion against the Crown would be punished through land confiscation. The entire of The King’s Country – 1.2 million acres – was confiscated the following year. While the primary settlements of Ngāti Koroki-Kahukura lay outside the aukati line at Karāpiro, Fred’s ancestors retreated to the bush-clad slopes of Maungatautari cut off from the awa that connected them to the broader region and the gardens and industries that were the basis of their prosperity.

In the following decades, Ngāti Koroki-Kahukura were dispossessed of their lands and livelihoods through a process of systemic deprivation. Lands were surveyed and assigned individual titles through the processes of the Native Land Courts, with further land seized as payment for this imposed process. Unable to use their remaining lands as surety against loans for economic development, Ngāti Koroki-Kahukura were forced to relocate in search of income. There were, however, rare opportunities for Ngāti Koroki Kahukura to remain within their rohe.

Fred was born in 1928 and raised in Horahora, an ancestral papa kainga at the centre of Ngāti Koroki Kahukura territory. His father, Kiwa Graham, was employed at the Horahora hydroelectric power station built in 1914, which harnessed the energy of the rapids to drive the turbines at the station and transmit electricity to the Waihi Mines seventy miles away. In 1919, the New Zealand Government purchased the station to provide electricity to the northern North Island of New Zealand and enable the mechanisation of dairy farming on the alluvial plains of the King Country. Fred was the only Māori child educated at the Horahora Power Station school.

In 1940, the Ministry of Works began the construction of the Karāpiro dam, which would supersede and subsume the Horahora Power Station and surrounding area – Ngāti Koroki-Kahukura were not consulted in any capacity. In 1947, Fred was one of more than 25,000 people who gathered to watch the Waikato River rise behind the dam, flooding the river valleys and plains, ancestral settlement sites, historic landmarks and washed ancestor bones from caves and urupa. The Grahams moved to Hamilton, the main city of ‘The King Country’, and shortly after, Fred enrolled at Ardmore Teachers College, where he was selected for an experimental art education programme where he eventually found himself among a community of like-minded Māori artists.

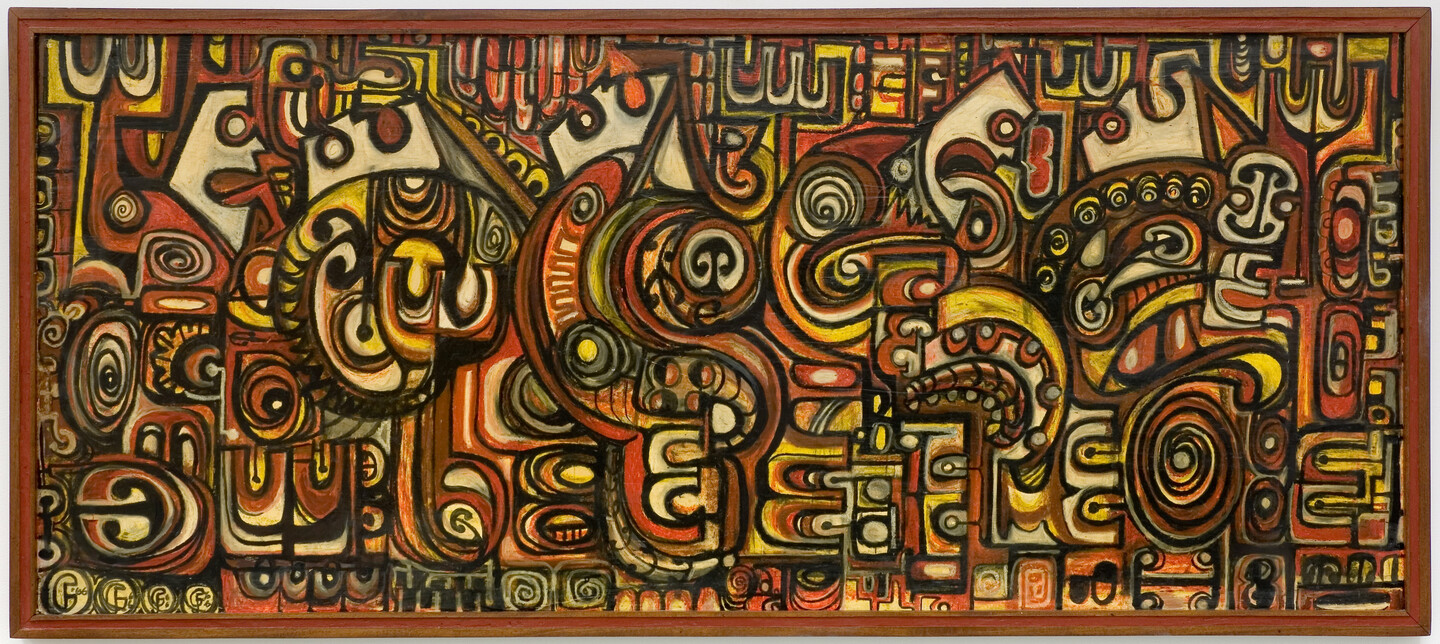

Fred Graham Whiti Te Rā c. 1966. Oil stick on board. Collection of Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, purchased 2008. Exhibited in Toi Whakaata/Reflections

The earliest work in Toi Whakaata dates to 1965, more than a decade after Fred became involved with Hirini Moko Mead, Muru Walters, Ralph Hotere, Arnold and Selwyn Wilson, Para Matchitt, Cliff Whiting, Elizabeth Ellis, Kathryn Harrison and Mere Lodge through his career as an art educator. Fred’s work from this period tells rousing adventure stories drawn from pūrākau (origin stories, mythologies and parables) and historical events as a counterbalance to the Eurocentricism of New Zealand culture. Whiti Te Rā c.1966 is a stunning example of the complex marriage of Māori and European abstraction: a flat field composition, uniformly patterned with no single focal point. A frenzy of motifs – rauru spirals marking buttocks with kape rua limbs terminating in three digits – is a fitting rendering of the famous Ka Mate haka, composed by Te Rauparaha – who was raised by his mother’s people at Maungatautari – and records his exhilaration at escaping a near-death situation. What initially appears as an upraised three-figured hand – a well-known symbol in Māori figurative design and emblematic of a fighting spirit – is a series of faces; two in profile with protruding tongues and three turned skyward, echoing the suffering plea of the figure in the far right of Picasso’s Guernica 1937, who was a major inspiration for these artists at this time.

Fred Graham Māui Steals the Sun 1971. Mahogany. Private collection, exhibited in Stranieri Ovunque - Foreigners Everywhere

The three-fingered motif is an important and recurring symbol in Fred’s oeuvre, which has otherwise been associated with stylised birds as a symbol of his Waikato-Tainui identity.3 After Whiti Te Rā, Fred further developed his figurative representation, as demonstrated by Māui Steals the Sun 1976, where the protagonist is indicated solely through his outstretched arms. The three-fingered motif then became the primary visual code in the wall relief, Kurangaituku and Hatupatu 1976; note how the fingers curl inward in the bottom left corner to create the facial features of Hatupatu hiding from the bird-woman in the rock at Ātiamuri. Eventually, the three-fingered motif – devoid of any facial features--constitutes the entire body to become Fred’s signature figurative style.

Fred Graham Kurangaituku and Hatupatu 1976. Kauri. Private collection, exhibited in Toi Whakaata/Reflections

Fred was not the only Contemporary Māori Artist to foreground the three-fingered motif in his practice. The upraised hand is also present in the work of Arnold Manaaki Wilson (Ngāi Tuhoe, Ngāti Tarāwhai) and Paratene Matchitt (Ngāti Porou, Te Whakatōhea, Te Whānau ā Apanui) and the importance of this motif goes beyond Māori visual traditions. In their work, this motif referenced the peaceful gospel of the nineteenth-century Māori prophetic movements that emerged from the Pai Mārire (or Hauhau) religious practice of Te Ua Haumene, a belief system signalled by an upraised hand.

In 1862, Taranaki religious leader and Kingite Te Ua Haumene began to preach the Pai Mārire faith, which promised deliverance to Māori and the restoration of their lands through the practice of peace. The Pai Mārire movement was actively suppressed in Taranaki by Government forces in concert with missionaries, though not before the teachings of Te Ua had been passed to the second Māori King, Taiāwhio, and has been safeguarded by Waikato-Tainui to the present day. Similarly, after being imprisoned with Pai Mārire followers on Te Wharekuri in the late 1860s, Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Tūruki (Rongowhakaata) developed the teachings of Pai Mārire as Ringatū, ‘ringatū’ meaning upraised hand. Persecuted and hunted by Crown forces, Te Kooti was protected by Tūhoe in Te Urewera, who have safeguarded the Ringatū church to the present day. While the upraised hand signals a commitment to peace in the face of aggression, Wilson, Matchitt, and Graham wield this motif in their work as statements of muscularity, resilience and pride in the morality of their ancestors’ defence of their lands. Indeed, the vigour of their work from the 1970s –and what Fred’s work brings to Foreigners Everywhere – speaks of a biding energy and noble patience for justice to prevail.

From the beginning of British colonisation, Māori have exhaustively sought equality in their relationship with the Crown, appealed for justice through the British legal system and appropriated those systems to create equal platforms for peaceful negotiation. On this point, Waikato-Tainui has been exemplary. After the Crown confiscated the King’s Country, Waikato Tainui pursued every avenue of redress, from direct negotiation with the Government, petitions to Queen Victoria in London and claims through the Native Land and Compensation Courts. For Ngāti Koroki-Kahukura, the local court was established in Cambridge in 1865, a military settlement first established to service the gunships patrolling the Waikato River during the war. The hearings required them to travel into town, camping for weeks near the lake known today as Te Kōutuutu – ‘meaning to scoop up and splash your face with water ... a method for cleansing and regenerating spiritual health’ after insufferable court experiences. 4 For these reasons, Cambridge became known as Te Oko Horoi, the washbowl of sorrow.

In 1881, King Tāwhiao returned to public life, having ruled in isolation after the invasion of his territory in 1863. Arriving unexpectedly at the southern military settlement, Alexandra, Tāwhiao laid his gun at the feet of the area commander. He then travelled through the district, ritually washed his face at Te Oko Horoi and visited his father’s tomb at Ngaruawahia. There, he made the following statement known today as a tongikura (famous saying of the King):

Ko Arekahānara tōku haona kaha

Alexandra (Pirongia) will be a symbol of my strength of character

Ko Kemureti tōku oko horoi

Cambridge a symbol of my wash bowl of sorrow

Ko Ngāruawahina tōku tūrangawaewae

And Ngāruawāhia my footstool5

In 1995, Waikato-Tainui became the second iwi to settle their Treaty of Waitangi claim with the Crown. No doubt, inspired by these flourishing conditions, Fred created the exhibition Ngā Pou o Potatau: The Pillars of Pōtatau at the Waikato Museum Te Whare Taonga o Waikato in 2004. The exhibition comprised 13 wall relief sculptures purchased in their entirety for the Waikato Raupatu Lands Trust at the behest of the Māori Queen, Te Arikinui Dame Te Atairangikaahu.

Fred Graham Washbowl of Sorrow 2004. Stainless steel, kauri, tōtara and custom wood. Waikato Raupatu Lands Trust/Visual Arts, Waikato museum, exhibited in Toi Whakaata/Reflections

Washbowl of Sorrow is a rare moment of mourning in Fred’s practice. The composition involves the three locations identified in the tongikura of King Tāwhiao. At the centre is a golden bowl – Te Oko Horoi – shaped from kauri wood. At left, the tīwhana (forehead moko design) of King Tāwhiao – the ultimate symbol of his strength of character – simulates his act of kōutuutu at Te Oko Horoi, with the marbled grain of the kauri appearing as water, tears or hupe, dripping from the King’s face and pooling at the base of the bowl. The bowl itself is couched in the sturdy stance of a pair of feet, representing Ngaruawahia as the turangawaewae of the Kingitanga. Constructed from stainless steel, this mirrored surface incorporates the viewer’s reflection into the work as though to ask, ‘And where is your home?’ While a shallow relief work, overlapping takarangi spirals fill the background, indicating the breaking of light bringing knowledge and hope into the world as promised by the claim settlement. Beyond its elegiacal tone, Washbowl of Sorrow is a singular work within Fred’s practice for incorporating a literal reference to facial features and foregrounding feet, firmly planted, which stand in marked contrast to the urgency of the outstretched and upraised hands that had dominated his work to this time.

Brett Graham's Wasteland with Fred Graham’s Nga Tamariki o Tangaroa (1970) in the background at left, Stranieri Ovunque - Foreigners Everywhere

At Venice, Fred’s work is placed near Brett Graham’s Wasteland, a settler wagon with outstretched arms is pleading for rescue from a swarm of tuna, a manifestation of the signature Waikato-Tainui whakatauki – “He piko he taniwha, he piko he taniwha, Waikato taniwha rau”, at every bend, is a leader. Wasteland embodies the tenacity demonstrated by the iwi to act as kaitiaki for the Waikato awa and bodies of water within their rohe, such as Te Kōutuutu, polluted through farming. Unto itself, Wasteland consumes the curatorial premise of indigenous people as foreigners in their land, and read together, the work of Fred and Brett Graham utterly disputes any concept of foreignness being part of their indigenous consciousness.

Pedroso admits that Foreigners Everywhere is a speculative concept that invites discoveries along with way, and of course, this theme makes an appeal on behalf of “foreigners, immigrants, expatriates, diasporics, émigrés, exiles and refugees” suffering the land wars of Europe and elsewhere. But as a platform for indigenous artists, Foreigners Everywhere is an elaborate curatorial conceit that needs to be accepted as making false claims for a greater good, though, if left unchallenged, diminishes the sanctity of this work and may serve the anti-indigenous rhetoric of leading voices within our current Government.

This article was first published in Art New Zealand, no. 202, winter 2024, pp. 100-107 and is reproduced online here with permission.