A Gathering Gravity

Anticipating Grant Lingard: Needs and Desires

Grant Lingard Mummy’s Boy—Smells Like Team Spirit c. 1995. Soap. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, gift of the estates of Grant Lingard and Peter Lanini, 2001

My encounters with Grant Lingard’s works have been few and fleeting. My information derives largely from the archive. The show has yet to open and I know only the title. But I am deep in speculation about what it will bring.

Grant Lingard Swan Song 1995–96. White enamel-coated laundry drying racks, sheets, pillowcase and towels. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, gift of Trevor Fry, 2013

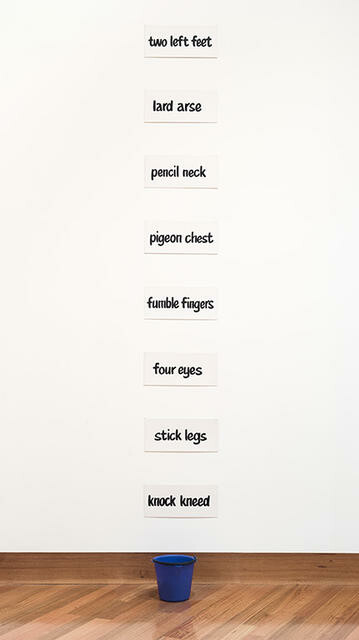

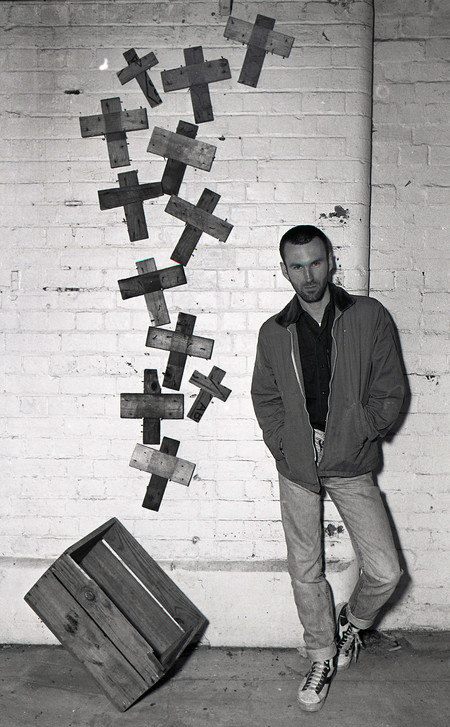

I envision multiplicity. Bewitching constructions of salvaged wood – things bashed together from things previously smashed apart. Effigies cloned using stencils and stamps, recalling branded boxes, home-made stationery, punk tattoos. Parades of hospital-white linen, the antithesis of dirty laundry. I anticipate sensitivity. Poetic reflections on the group and the self, on gender expression and sexuality, and on the ways these things flutter their wings and metamorphose. Whimsy and pathos in potent balance. A wit that traverses materials and words, trading in pure sensation.

What is certain is that Needs and Desires carries a weight of expectation. Its subject, Grant Lingard (1961–1995), was born and raised on the West Coast of Te Waipounamu and spent his adult life in Ōtautahi and Sydney. The last major retrospective of his work, Desire and Derision (1996), took place at the Jonathan Smart Gallery over a quarter of a century ago.1 The gap is not entirely surprising. As Jeremiah Boniface – one of the artist’s keenest champions, and an important contributor to the body of research on his work – has observed, Lingard faces special challenges when it comes to renewed attention.2 Many of his pieces are fragile, and the question of remaking them is fraught, since both the artist and his partner, Peter Lanini, have passed away. Yet a retrospective now feels necessary, as well as desirable.

Interest in Lingard has been gathering of late. April 2021 saw the Ilam Campus Gallery present the group exhibition TRUE LOVE: A Tribute to Grant Lingard, which emphasised his lingering artistic and personal impact on the art communities of Aotearoa in general and Ōtautahi in particular. Shortly thereafter, an important installation, Swan Song (1995–96), appeared in Crossings (a group show about intimacies and distances) at the Adam Art Gallery Te Pataka Toi. Lingard is increasingly recognised as a seminal gay artist – that is, an artist who publicly identified as gay and addressed gay issues in his work. To make a show about him is to make a show about a queer ancestor, and one whose importance only grows as New Zealand moves further in the direction of acceptance and seeks to celebrate queer heritages and histories.

Lingard’s status as a trailblazer is undeniable. His Box of Birds (1987) – with its connotations of the bravely chipper and insidiously squawky – was perhaps the earliest work by a local artist to respond to HIV/AIDS.3 Indeed, as David Herkt has remarked, it was in the vanguard internationally, being contemporaneous with the first pieces on the subject by Americans Felix Gonzalez-Torres and Keith Haring.4 Lingard was the driving force behind the landmark show Homosexual.5 This was held at the CSA Gallery in 1988, and comprised works by Trevor Fry, Paul Johns, Paul Rayner and Lingard himself. According to Boniface, the exhibition was the first at a public gallery in Aotearoa to expressly centre homosexuality.6 A Lingard solo of the same year, Incident in the Park, was likewise unabashed in its queerness, taking as its subject gay romance and the practice of cruising.

Grant Lingard Flag 1994. Mixed media. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1996

Having been born in the 1980s, I had my first meeting with Lingard’s work only relatively recently, when I visited Sleeping Arrangements (2018) at the Dowse Art Museum. The exhibition was curated by the 2017 Blumhardt Foundation/Creative New Zealand curatorial intern, Simon Gennard, and included a single, grand piece by Lingard, Flag (1994). Composed of a network of white Y-front Jockey underpants, the work is one of the artist’s best-known. It was widely shown as soon as it was made: as part of his solo Coop (1994) at the Jonathan Jensen Gallery; Tales Untold (1994), a multi-site public art exhibition organised by South Island Art Projects; and Art Now (1994), curated by Christina Barton, at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.7

Flag is an instance of Lingard working in a mode that is maximally bold, provocative, and – to use a rather freighted term – proud. White flags are, of course, associated with surrender; however, as Gennard has observed, Lingard described the work as “a small Up Yours, victory for me the artist.”8 Writing in 1996, Brent Skerten referred to it as a “neo-Nazi flag”, suggesting that Lingard was teasingly condemning the white supremacist element within Christchurch by producing a holey, all-white flag made of underpants.9 Moreover, Lingard linked white Y-fronts with gay fetish and sex, bending popular conceptions of the garment, a staple of blokes everywhere, and of the Jockey brand, which was plugged by rugby players in the past, just as it is today.

During Tales Untold, Flag flew outside the ur-institution of the Canterbury Museum. In the basement of the nearby Robert McDougall Art Annex, Lingard painted the walls a sticky-looking black, creating a space reminiscent of a crypt, sacristy, and sex dungeon – and perhaps, too, echoing works from Coop featuring tar and feathers. A bed and table adorned with cloths made of Y-fronts were installed. In the catalogue, Vivienne Stone and Giovanni Intra drew a connection with the ‘old boys’ network’ of Christchurch. No doubt, Lingard was also poking fun at the condemnation of non-heterosexual relationships by many within the Christian Church, and getting at the ritual and spiritual dimensions that can attend sex practices that outsiders might fear or abhor. The cloths were clean, but soiling – by sweat or other excretions – was obviously implicit.10

Grant Lingard Hutch and Lure (detail). Cotton, soap. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, gift of the estates of Grant Lingard and Peter Lanini, 1998

Art Now as a whole ruffled feathers, attracting sarcastic commentary. A writer for the Evening Post griped about the prevalence of everyday objects and insinuated that the show was pretentious.11 Lingard’s Hutch and Lure (1993) proved especially divisive. It comprised ten white Y-fronts arranged in a circle on the floor. In the crotch of each was nestled a piece of fruit made of soap, a direct reference to the homosexual slur ‘fruit’. One visitor apparently grumbled, “My five-year-old grandson can do that.”12 Another filed a complaint, claiming that her children had been “putting fruit down their underpants and running around with it”.13 Perhaps the work was behaving as intended, tapping into common processes of experimentation and self-exploration, including the recreation of genitals and breasts using everyday entities.

Like much of Lingard’s later work, Hutch and Lure is outwardly simple but rich in associations. One might think of a messy bedroom or school locker into which gruds and old pieces of fruit have been tossed. One might think of the good-enough-to-eat scent of fruity soaps and the smell of bodies, washed or otherwise. The work was first exhibited as part of a Sydney Mardi Gras group show, Crush (1993), and later as part of an important solo, Smells Like Team Spirit (1993), at the Jonathan Jensen Gallery. In both contexts, Lingard placed an emphasis on the game of rugby, which has long been a focus of masculinist culture in Australia and New Zealand, marked by homophobia and – paradoxically – a site of discovery for gay boys via the changing room, field, billboard and screen.

The title Smells Like Team Spirit, which was also applied to Lingard’s overall contribution to Art Now, points to an important aspect of his practice: the use of puns. It alludes to the well-known Nirvana song Smells Like Teen Spirit (1991). By changing ‘teen’ to ‘team’, Lingard at once drew attention to teenage life – with all its foul and heady smells, self-reflection and self-loathing – and emphasised the question of belonging. Other works created about the same time likewise get at the sense of being part of, or ostracised by, a group. Sin Bin (1993), a bench covered with rugby boot sprigs that featured in Crush, evokes rejection of the ‘sinful’ by religious groups, as well as those relegated to a bench during a match for misconduct.14 Conversely, it might also be understood to suggest acceptance within bondage or punk circles.

Grant Lingard Flower Bed For Sweet William (detail) 1990. Mixed media. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetu, gift of the estates of Grant Lingard and Peter Lanini, 1998

Grant Lingard with Box of Birds. From The Press, 22 October 1987. Photograph courtesy of Stuff Limited

The Collector of Beauty, I–IV (1991) employs word play and visual puns, and invokes further images of youth. Butterflies in jars – exquisite creatures quite literally collected – are presented alongside panels that mimic minimal abstract paintings but are in fact pigmented using cosmetics. I suspect that there are personal stories at play. Certainly, Lingard was an inveterate collector, including of magazines and records. The butterflies are toy-like fakes of enamelled tin. This enhances the tension between artifice and authenticity. There is a sense, too, of the beautiful and seemingly vulnerable constrained and under scrutiny. Those who make themselves up might seek liberation, through performance, or through the creation of outsides that better reflect insides. They also, very often, become trapped within suffocating structures of judgement.

Such structures can be seen to underlie Somewhere Between Heaven and Earth Here and Now in the New Age Cosmos (1988), which was originally included in the inaugural exhibition at the Robert McDougall Art Annex, Here and Now: Twelve Young Canterbury Artists (1988).15 The work is, to my mind, typical of Lingard’s practice, being pared back and textured, incisive and poignant. It features two identical white towels resting on flimsy rails. These are mounted beneath twin framed copies in silhouette of the forearms of Adam and God as depicted by Michelangelo on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. The limbs peek through milky surrounds that recall clouds or steamed-up glass. The compact installation resembles other 1980s works by Lingard, which play with replication to suggest homosexuality but also conformity, or the expectation of the same.

As with pieces like Mummy’s Boy – Smells Like Team Spirit (c. 1995) – a pair of footy boots made of Sunlight soap – and Hutch and Lure, there is an apparent emphasis on cleanliness. In Somewhere Between Heaven and Earth Here and Now in the New Age Cosmos, though, the logical context is not the washhouse. There is no soap to scrub clothing clean, or to wash out a filthy mouth. The work instead connects with the bathroom, or the toilet, and evokes moral purity. I think of images of the Virgin at her washbasin, immaculate, without sin. The implied opposite is the ‘unclean’ gay man, who finds Adonises in heaven, who imagines any pair of men as lovers, who lingers in the cheap motel, the sauna or the public convenience.

The picture frames within the work carry neat plaques. Etched with the expressions ‘running hot’ and ‘running cold’, they echo nameplates of the sort that nurses might wear, or labels found on paintings from centuries past. The phrases call to mind inconstant showers, emotions alternating between warmth and coldness, fluctuating body temperature, and, therefore, a person fighting disease. Perhaps because Lingard ultimately died from AIDS-related illness, I tend to focus on associations with HIV/AIDS, reading the installation as a reflection on the effects of the epidemic on queer people, and the phenomenon of attaching to the illness a moral judgement with ungodly consequences. Modest as it is, the work has become for me a powerful emblem of its moment and, indeed, of the queer art history of this part of the world.

The ‘here and now’ of Aotearoa in 2022 is the product of significant changes. Medications enable many who live with HIV to do so indefinitely, and support the curbing of transmission. All manner of stigmas pertaining to queer people have diminished. Lingard’s works bear witness to a past that was often dark, and they helped to pave the way for a present that is in some ways brighter. At the same time, embracing sensuality and wit as they do, they stand as reminders not to overplay the gloom. The recent past was populated by capable, wise, exquisitely complex experimenters. Some, like Judy Darragh and Paul Johns, are with us still. Others, like Lingard and Julian Dashper are now cosmonauts. Yet their art and their influence endure. Their gravity pulls at us, and, as new audiences experience their works, the force gathers. It will only ever gather.