The Arts and Crafts Movement at the End of the World

![Attributed to Samuel Hurst Seager [Homebush Brick, Tile, Terracotta and Pottery Works Glentunnel, Canterbury, New Zealand, 1872–1983] Architectural exterior tiles / patera 1886. Unglazed earthenware (terracotta). Collection of the Pumphouse, Christchurch](/media/cache/a8/cd/a8cd1e1e311113c0adbc7c7a99898d81.jpg)

Attributed to Samuel Hurst Seager [Homebush Brick, Tile, Terracotta and Pottery Works Glentunnel, Canterbury, New Zealand, 1872–1983] Architectural exterior tiles / patera 1886. Unglazed earthenware (terracotta). Collection of the Pumphouse, Christchurch

It is interesting to ponder how makers involved in the Arts and Crafts Movement might respond if they were able to see their works on display in galleries today. While exhibitions on a range of scales were central to the Arts and Crafts, and played a key role in how its ideas and objects reached new audiences and took root across the world, today’s retrospective explorations of the Movement are to some extent testament to the fact that it never revolutionised art and life to the extent that its protagonists had initially hoped.

Upon visiting recent displays of their work then, would they celebrate the close looking that exhibitions enable, and the way in which this might encourage respect for handcraft? Would they welcome seeing craft presented as being on a par with – or perhaps even inseparable from – ‘art’? Or, might they mourn the missed potential for their objects – and for the Arts and Crafts Movement more generally – to have been woven throughout the fabric of everyday life, to have been in use as part of an ethically and aesthetically harmonious domestic environment? How might they feel to see their works off-limits to touching hands, given the centrality of haptic understanding and materials within the Movement? Would they read into museums’ and galleries’ collecting of Arts and Crafts objects yet further confirmation of how deeply the capitalistic compartmentalisations and hierarchies they rejected have permeated today’s world, or would they be encouraged by the care and interest with which institutions and viewers today treat their movement and its objects?

For a movement as pluralistic and sprawling as the Arts and Crafts, all of these responses are conceivable. The Movement spread internationally, lasted for around a hundred years (spanning most of the second half of the nineteenth century and, in Australasia at least, reaching the second half of the twentieth),1 and encompassed such a wide variety of craft skills, people and ideas that boiling it down to unifying tenets is difficult. However, musing on how Arts and Crafts makers would react to exhibitions today, or the contemporary world more generally, sheds light on what they were originally trying to achieve – and also exposes the potential for misunderstandings when looking back on the Movement from the perspective of the now. While many recent commentators have described the aims of the Arts and Crafts Movement as naïve, owing in part to its desire for thoughtfully-crafted (and preferably hand-made) homewares to be available to all, this dismissal overlooks the fact that it was the capitalist system that made these objectives incompatible. Indeed, exactly as Arts and Crafts thinkers feared might happen, so completely has capitalism lodged itself within the way society is imagined today that many have ‘naturalised’ it, losing the ability to see through or past it. However, while today it might be “easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism”, to borrow an oft-quoted idea from Fredric Jameson,2 for nineteenth-century adherents of the Arts and Crafts Movement, capitalism was a much newer and less entrenched system. It was therefore more straightforward to imagine it ending – not necessarily as an apocalyptic scenario, but as a return to something healthy and wholesome after a period of temporary hysteria. While the Arts and Crafts Movement had many failings, its refusal to shape its ideals to align with capitalism is not one of them, as this was the very system it was initially seeking to challenge.

Alice Beatrice (Biddy) Waymouth Silver teapot c. 1908. Silver-plated copper, rosewood. Private collection, Christchurch

In confronting capitalism, material objects were recognised by the Arts and Crafts Movement as playing a key role. While the Arts and Crafts was described by the British book designer and activist Thomas James Cobden-Sanderson as “a movement in the main of ideas and not of objets d’art”,3 in reality the theory and practice were not so neatly separable. Instead, objects were seen as carriers of ideas, and as a means by which both makers and users could be morally uplifted. The Arts and Crafts therefore believed in the capacity of art to change society, rather than merely to reflect it – though perhaps paradoxically, some practitioners also thought that until capitalism was over, crafted objects could never really reach their full potential.

A key way in which art – a term that the Movement hoped would become interchangeable with ‘craft’ – could embody ideals was by containing evidence of the methods and conditions of production. For example, visible hammer marks on the surfaces of metalwork might bear witness to the hand of the maker, and it was believed they indicated that the maker’s working conditions had been sufficiently liberated to enable the choice to work slowly and in traditional ways. Unnecessary striving in processes of making was also to be rejected: imperfections were celebrated, and the forms of objects were to be guided by the properties of the materials used. By extension, media were to be selected carefully in order to facilitate the craft practices involved in the realising of designs. Furthermore, the Arts and Crafts Movement’s emphasis on local materials and motifs was also intended to resist the structures of capitalist supply chains, and to help create objects that were sensitive to their environments.

These ideals, however, left room for contradictions, and were seldom all followed exactingly. Even within a single object then, conflicting ideas could be expressed. Charles Kidson’s peacock plate, for example, reflects Arts and Crafts principles in the choice of the materials used, with the pāua shell deriving from Aotearoa’s coastline, and copper being a malleable metal that was conducive to repoussé techniques. However, the peacock motif is incongruous, since peacocks were neither particularly relevant to the function of a plate, nor endemic to Aotearoa. Indeed, in New Zealand’s Arts and Crafts Movement it was not uncommon to see introduced species featured in designs, despite the fact that their use as motifs ran counter to the Movement’s stated emphasis on drawing from ‘locally appropriate’ examples and ‘nature’ for design inspiration. Arguably, this reflects the cognitive dissonance among British settlers as to where exactly ‘Home’ referred to (the term was frequently used in newspapers of the day to refer to Britain), as well as the extent to which the nineteenth century saw significant accelerations in the importation and exchange of species of flora and fauna. This was especially apparent in colonial contexts. The Arts and Crafts edict to reference ‘nature’ was therefore complicated by the emergence of increasingly hybrid environments.

Charles Kidson Peacock Plate 1903–04. Copper and paua shell. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetu, gift of R. J. Eltoft, 2003

Colonial contexts also highlighted assumptions at the core of the Arts and Crafts, and shaped how the Movement took root in these places. A key Arts and Crafts directive – linked with the emphasis on local materials – was looking to nearby vernacular forms and buildings for inspiration for designs. In Aotearoa, the Movement’s response to Māori art was mixed and problematic: while some, including Samuel Hurst Seager, myopically dismissed Māori architecture as “scarcely suitable as standards on which to found our national taste”,4 others were fascinated by indigenous art, and saw toi Māori as a rich visual tradition from which to draw. However, the way in which Māori work was referenced in the Arts and Crafts objects of Pākehā designers was appropriative and frequently inaccurate, and often lacked the cultural understanding that was central to these artforms and their contexts. The desire of the Arts and Crafts to draw on local vernaculars therefore meant that the Movement could be colonising and destructive, and in Aotearoa as elsewhere this sometimes had the effect of distorting understandings of traditional art.

It is perhaps ironic then that imperial anxiety back in Britain – alongside fears for the environment, mounting evidence of the dangers of extractivism and poorly-regulated mechanised production, and concern for people marginalised by inequitable systems – was part of the context from which the Arts and Crafts originally arose. The homely focus and utopian romanticism of the Movement might indeed be traced to the fact that it was born at the coalface of industrialisation – almost literally, given the role that wealth amassed from mining and other forms of ‘resource’ extraction played in funding so many Arts and Crafts commissions, and the careers of a number of its major protagonists. These included William Morris, recognised by his contemporaries and still today as the Movement’s leading light. However, finding themselves with a front row seat to extractivist capitalism’s worst excesses, Morris and others did not accept this as the status quo, but leveraged their insights to launch the experimental critiques and forms of artisanal resistance that gave rise to the Arts and Crafts Movement. While scholars often mention the Arts and Crafts’ desire to remake a sort of prelapsarian world, before the mechanisation and industrialisation that the Movement saw as having eroded standards of art and production, perhaps the most crucial aspect of this was that it envisioned a world without capitalism. It is then yet another irony of the Arts and Crafts Movement that the beauty and enduring appeal of its designs, combined with its failure to fully transform society in the way it had hoped, has resulted in its objects becoming commodified, and separated by walls and display cases from tactile and everyday interactions with people within their domestic lives.

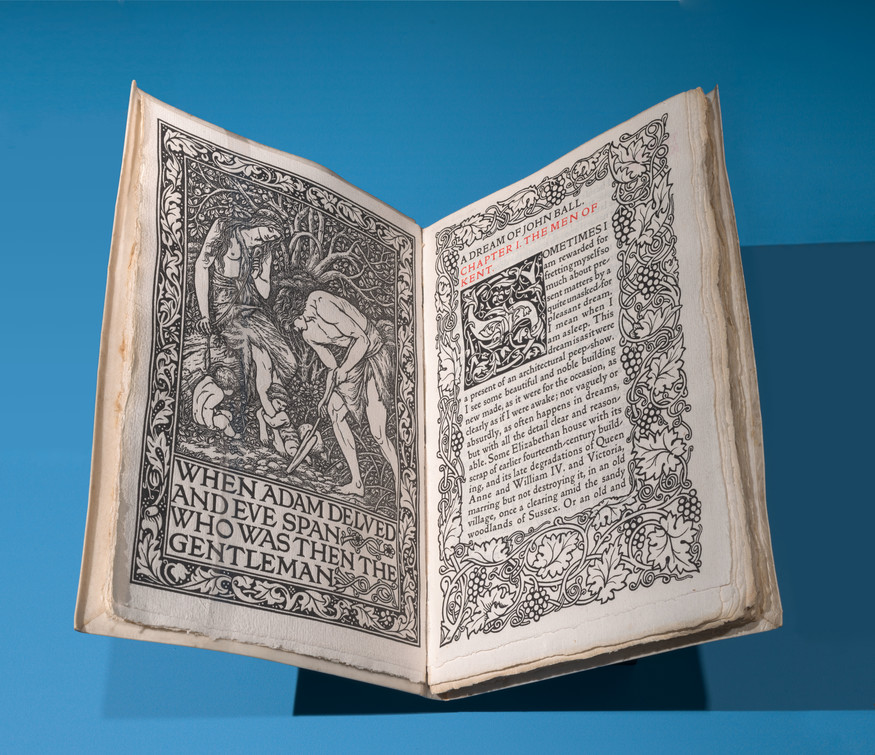

Illustration by Edward Burne-Jones in William Morris A Dream of John Ball 1892. Kelmscott Press. Macmillan Brown Library, University of Canterbury collection