Gordon Walters

and the tradition of mark making in Te Waipounamu

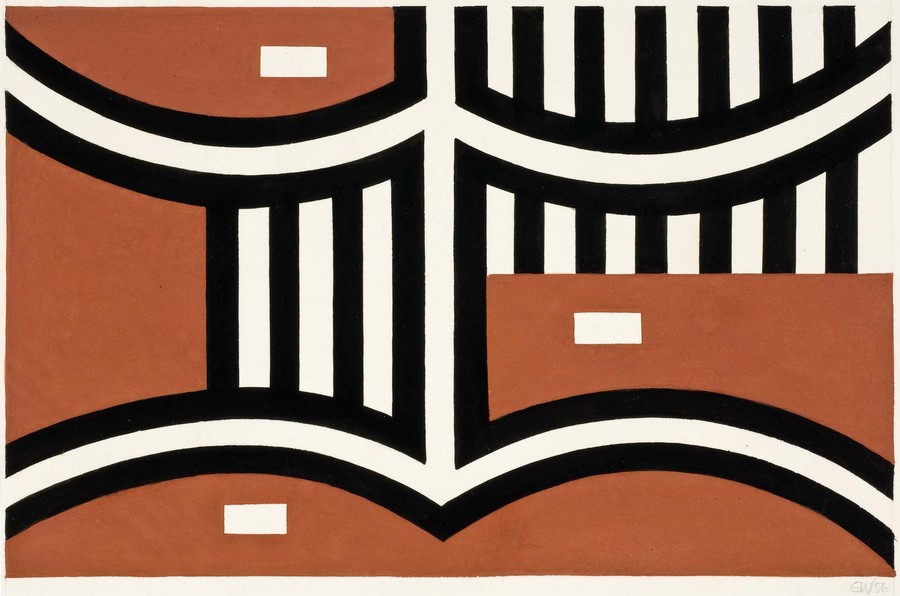

Gordon Walters Untitled 1956. Gouache on paper. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased with the assistance of the W.A. Sutton Trust 2010. Reproduced courtesy of the Gordon Walters Estate

Te Waipounamu the South Island is crisscrossed by hundreds of traditional mahinga kai, or food-gathering, routes. Used by Waitaha, Kāti Mamoe and Kāi Tahu people over centuries, these routes provided access to the best destinations to harvest food, as well as facilitating the transport of pounamu from the Arahura through Nōti Raukura (Browning’s Pass) across Ka Tiritiri o te Moana (the Southern Alps) to Tuahiwi, north of Christchurch.

Along the routes in Canterbury and Otago are limestone shelters and caves that provided ideal spots for respite. The soft, chalky limestone provided a workable surface for carving, drawing in charcoal, or ochre pigment painting, and there are several hundred known sites in which art expresses something of Te Ao Māori (the Māori world), tribal identity and whenua (land). In mid-1946 Gordon Walters visited Theo Schoon as he recorded the art found at sites near the Ōpihi River in the takiwā (district) of Te Rūnanga o Arowhenua. The experience proved deeply significant for both artists.

The sites had been visited and recorded by Europeans like government land purchase agent Walter Mantell as early as 1848, while artist Thomas Shelby Cousins, who made several trips during the 1870s, recognised the taonga as both drawing and painting. Ethnologist Augustus Hamilton photographed a number of well-known sites in 1896. A number of artists of the twentieth century have also engaged with the drawn and painted taonga, and some have created paradoxes over time. Tony Fomison, Bill Sutton, Theo Schoon and Gordon Walters are some who in various capacities ventured into the territory of somehow representing the art of Waitaha, Kāti Mamoe and Kāi Tahu.

Cousins, Sutton and Fomison maintained a distance,1 contextualising the taonga within the landscape or copying for the purpose of conservation. Walters and Schoon drew upon their observations and various recordings as purposeful studies towards their own artistic practice, riffing on the work. As participants in an established modernist approach to art-making, Schoon and Walters have been drawn into the critical discussions around cultural appropriation, as expressed by Ngahuia Te Awekotuku regarding the so-called koru designs of Walters. New Zealand’s art world has struggled to reconcile the complexities of the issue.2

The development of photography and the expansion of the British Empire may not typically be paired together when thinking about modernist painting in Aotearoa New Zealand, but an attempt to contextualise shifts in culture and art can help us consider the art of Gordon Walters.

Joseph-Nicéphore Niépce was the first to fix a permanent photographic image by way of his heliography (sun drawing) process in 1822. His first success was a copy of an engraving superimposed on glass and, by 1826–27, he would famously achieve the first photograph taken from nature, a view of the roofline seen from his upstairs workroom window. Photography quickly began to challenge painting as a mode of representing the world.

At around the same time, William IV was king of Great Britain, Ireland and Hanover. A progressive monarch, William set several acts of reform into effect—the poor law was updated, child labour restricted, slavery was abolished throughout most of the British Empire and the reform of the British Electoral system was begun by the Reform Act of 1832. In New Zealand, on 28 October 1835 the Declaration of Independence was signed between The United Tribes of New Zealand and King William. It declared all sovereign power and authority and other related things within the territories of United Tribes of New Zealand to reside entirely and exclusively with the hereditary chiefs. The King agreed to protect Māori in this capacity and from all attempts upon that independence.

The document offered the potential for Aotearoa New Zealand to begin its history within a truly bicultural framework. However, that promise and protection ended just two years later with the King’s death in 1837, and the New Zealand Company sought to establish a preferable document for the colonial project. This was further supported by the Crown’s adherence to the English version of the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi, while the Māori version maintained the integrity of the 1835 Declaration.

The Treaty opened a space for the Crown to begin land purchases, and between 1844 and 1863 Kāi Tahu sold land to the Crown in a series of nine purchases. Of these, the Canterbury purchase of 1848 was “the largest of all the Crown purchases from Ngāi Tahu and the least carefully transacted”.3

Part of that sale was the provision of ten acres of land per tribal member, the building of schools and hospitals on Māori land, and the protection of the traditional mahinga kai routes. Rather, Kāi Tahu received a total of 6,359 acres from the 13,551,400 acres purchased, no infrastructure and no access to the mahinga kai routes, which effectively drove them out of the developing economy. The Kāi Tahu grievance process was begun officially by rangatira (high ranking) Matiaha Tiramōrehu in 1849 and evidence by some European parties established fault by the Crown as early as 1881, but the process continued until the settlements of the late 1990s.

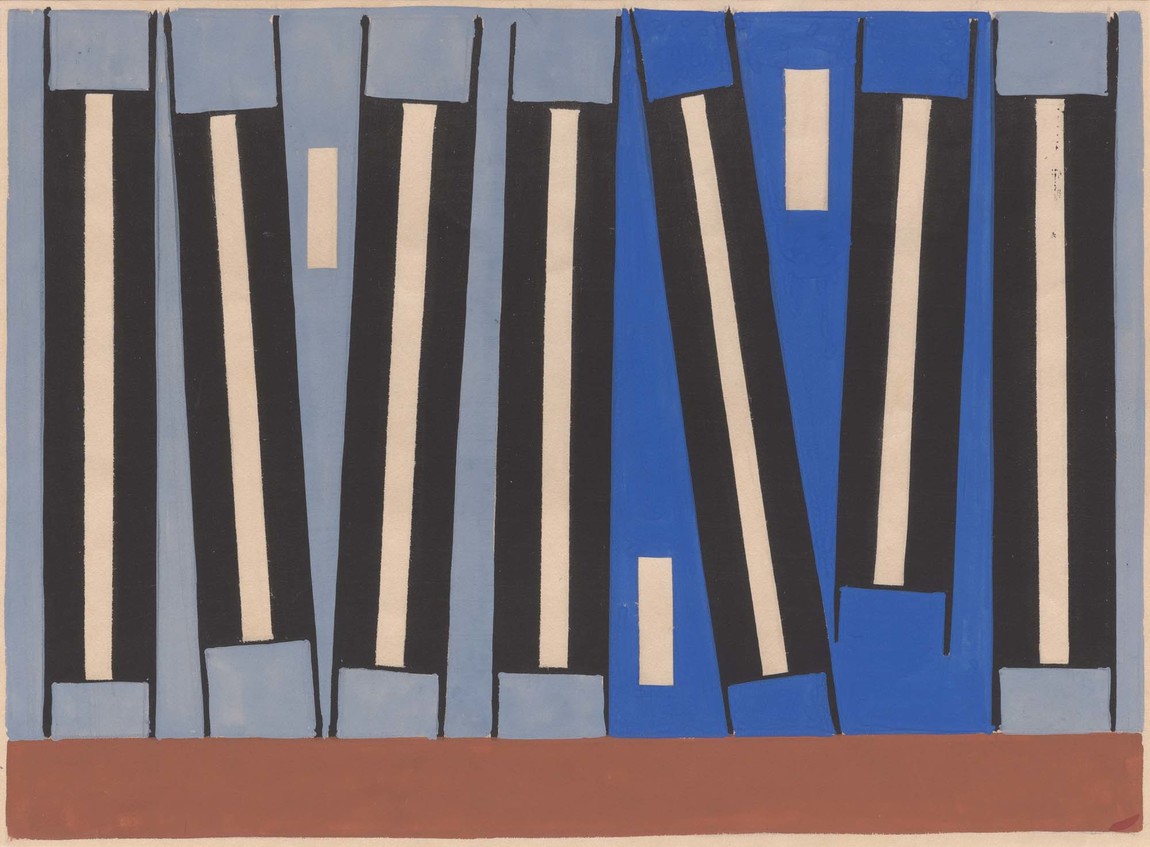

Gordon Walters Te Whiti 1964. Enamel on hardboard. Private collection, Auckland. Reproduced courtesy of the Gordon Walters Estate

The importance of the mahinga kai routes to Kāi Tahu cannot be underestimated, and this is deeply significant when considering the works of Schoon and Walters. The routes ran over most of the island and provided the principal means of connection, communication, harvesting and, along with the pounamu trade, maintaining the economic wealth of the tribe. But the loss of access to these areas through the 1848 purchase also saw that life, economy, and practice of drawing and painting upon the limestone shelters and caves of Te Waipounamu effectively ended.

Kāi Tahu saw their lands disappear, in much the same way as Edmond Becquerel’s 1848 experiments in full-colour photography, which existed for a moment, then due to the colours being so sensitive, faded before the viewer’s eyes.

From Niépce’s early experiments in photography to the 1875 achievements of Edward Muybridge, who photographed a sequence of a horse in motion, came the birth of cinema. All these societal and technological developments towards the turn of the twentieth century inspired the next generation of artists to develop new modern forms of painting to follow Impressionism, and that generation pushed for radical experimentation.

Primitivism was an artistic tendency which can be considered in a number of ways. One view holds that at the dawn of the twentieth century, representation had been triumphed by photography, so painting and sculpture were free to expand. Another view involves a rethinking of the potential found in indigenous art that allowed European artists to reject the dominant realist mode. Regardless, the concern remains that the appropriation of indigenous art found in museums and personal collections aligns with an imperialist positioning by way of the dominant culture’s existing practices. Whether intentional or not, this remains the major flaw of primitivism and modernism with regard to indigenous art. Modernism was not critiquing the Industrial Revolution or colonial imperialism, but rather inherited, seemingly without question, the spoils of the victor from which to attempt to build a utopic world.

The presence of Māori in European art might be first detected in 1916, when principal Dada leader Tristan Tzara recited a Māori-based poem, Toto Vaca, at the first Dada gathering at Cabaret Voltaire.4 Tzara was an Eastern European who immigrated to the “West”; he had a mind for world history and culture and significantly, let himself be “colonised” and “assimilated”. Tzara’s fascination with non-European art progressed from an indiscriminate interest during the World War I period into a politically informed, anti-colonial position by the late 1950s. Gordon Walters was born in Wellington in 1919 and spent a great amount of time in the Dominion Museum studying and drawing the exhibited art of Māori and other Polynesian cultures. He is recorded as finding the manner in which the new National Art Gallery of 1936 kept Māori and European art separate from each other “disturbing”.5 It’s a distinction that reveals something significant of Walters, and a great deal about the official perspective of New Zealand as propagated by the government. Walters would spend his life working in an international idiom with distinctly Pacific forms and motifs.

Walters met the Java-born, Netherlands-educated artist Theo Schoon in 1941, and in 1946 accepted his invitation to visit the mahinga kai routes of Te Waipounamu. Schoon had recognised the drawings and paintings as significant and loaded with artistic potential when considered through the modernist lens and had been recording (and sometimes interfering with) the drawings and paintings. Walters took the experience of visiting the taonga and added this to his previous years of studies, and it can be argued that his integrity towards indigenous art was manifest in his process of working and reworking, refining and drawing-out the essence of the forms to create something new. This is an accepted process of art making, whereby one copies in order to develop something new or unique.

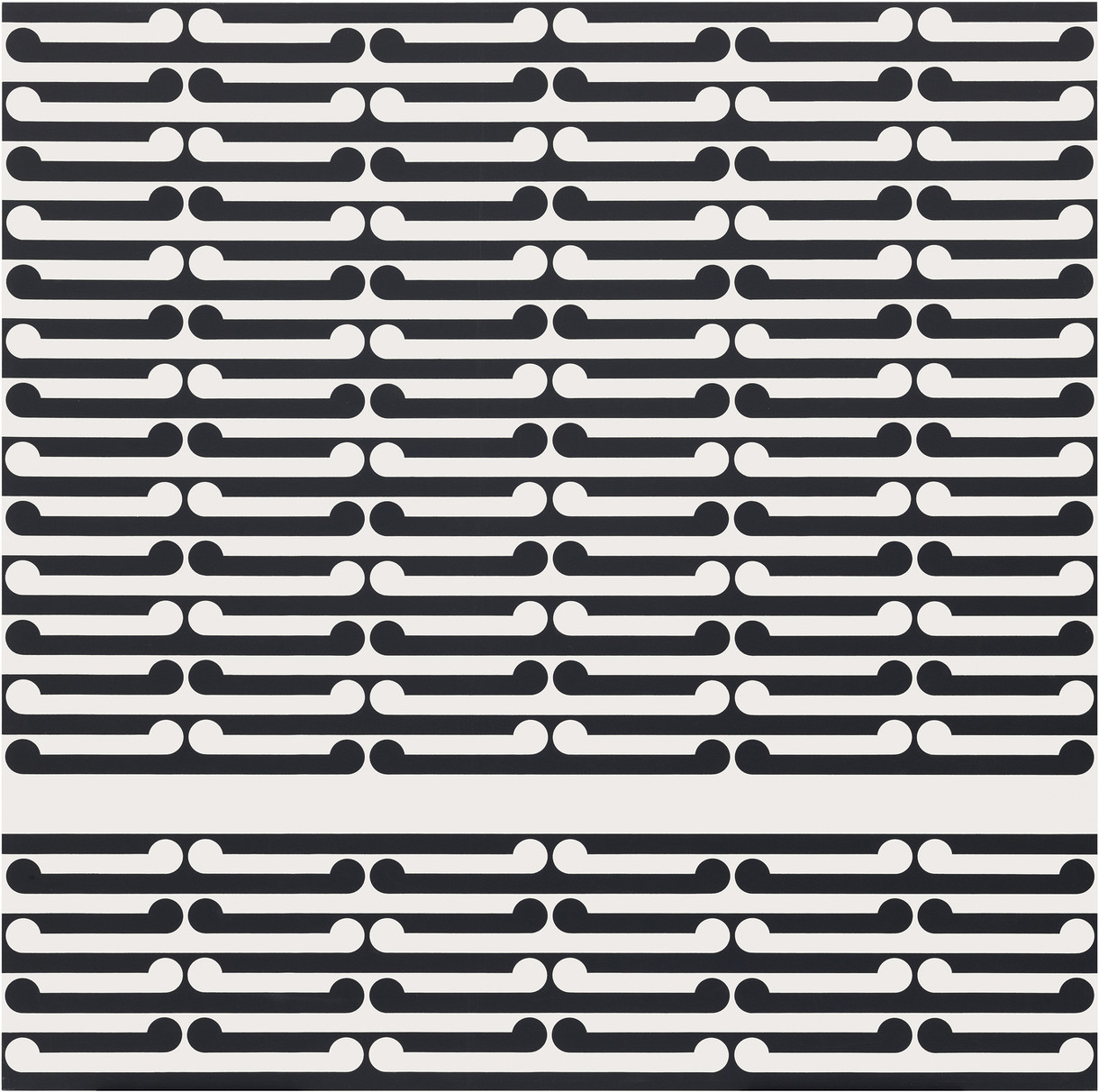

Gordon Walters Untitled 1955. Gouache. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2015. Reproduced courtesy of the Gordon Walters Estate

Walters however, does not seem to reveal an ethical or political position towards the action of working from Māori art as Tzara did (albeit in later life) and it’s this that creates tension around significant aspects of his painting. The resulting works demonstrate high modernist achievement, but what is that when the people who provide the influence are not engaged? How much more fully could we appreciate this aspect of his work if consideration had been given to grounding it in conversation with the Māori world?

Perhaps if the Nation Chiefs’ and King William IV’s idealism had been adhered to we would not have to face such difficult questions. For all it seems he attempted to bring together modernism and Māori painting, Walters will likely always remain problematic as he grew into a world where Māori were considered second-class citizens in their own land. That is certainly not to say Walters himself agreed with that politic—indeed his rejection of that was manifest in the multiple cultural references in his work—but it is how the world he lived in was framed.

His painting ventured into Te Ao Māori and other cultures through dedication and study, propelled by the Western understanding that art was free to take from anywhere for the progress of art. Art produces more art, artists eat artists—the vernacular is a given among artists, and reflects a particular notion as to how art works.6

Primitivism and modernism have in our times become retrospectively accountable for cultural appropriation. Paul Gauguin might be seen as the senior appropriator and in that same sense, when modernism ventured into Te Ao Māori it was on modernism’s terms. When a new generation of Māori artists from the 1950s ventured into modernism, they took Te Ao Māori with them. The spring of Māori Modernism (or modernist Māori art) came into being with the first Māori graduates from Elam School of Fine Arts; Selwyn Wilson in 1952 and Arnold Manaaki Wilson in 1954, the same year of the Northern Māori Project.

The juncture of cultural difference between the Māori and Pākehā worlds needs further discussion, as we are not a culture of one perspective, nor even two, but many, held within an ever-strengthening bicultural political structure that is yet to be fully realised at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Cultural difference remains an important conversation as ‘difference’ needs to be considered, made clear and understood within cultural contexts as a mode of living. Walters’s works contain at their core a sense of longing or striving for these things, yet seem to jump to visual solutions directly, void of cultural contact—that, for me, is what is most visually compelling and culturally problematic within the work.