Powerfully Present

Julia Morison Teaching Aid #1: Appropriate brushes for large flower paintings 2001. String, plaster, resin, galvanised pipe and set of ten wall labels. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2008

In the last issue of Bulletin, to mark the 125th anniversary of women claiming the right to vote in Aotearoa New Zealand, our curators wrote about five significant – yet lesser-known – nineteenth and mid-twentieth-century works from the collection by women.

In this issue we focus on some contemporary works by women artists that assert a powerful presence in the collection – and which variously explore the charged politics of representation.

Teaching Aid #1: Appropriate brushes for large flower paintings

Walking through Victoria Square in the autumn of 2013, I was brought to a standstill by three monstrous, dried-up flowerheads marooned in the shadow of the quake-munted Christchurch Town Hall. It took a long moment to reconcile these desiccated aliens with the cascading splendour of the Ferrier Fountain’s triple sphere de fleur, a sight that held me spellbound as a child and graced countless flashy postcards of the Garden City since 1972. Even in their dehydrated mode, they held a strange, apocalyptic beauty. Recently, visiting the collection galleries in that quiet half hour before the public arrives, I had another unsettling floral encounter. Rounding the corner, I came face-to-face with Julia Morison’s Teaching Aid #1: Appropriate brushes for large flower paintings, a wall’s worth of flowers at human scale. I wasn’t surprised to see them – they’re up as part of We Do This, an exhibition I curated with Lara Strongman – but, even in a room full of attention-grabbing showstoppers, their out-of-place-ness seemed suddenly magnified into an absurd grandeur.

Morison’s ‘brushes’ call attention to the region’s strong flower painting tradition, and also take a gentle swipe at Christchurch’s much-vaunted ‘Garden City’ status. Made when she was working as a painting lecturer at the University of Canterbury, the Teaching Aids were Morison’s tongue-in-cheek ‘how-to’ guide for students, her ironic exposition of the mechanics of painting. A rebuke to the idea that art, or teaching, could, or should, be measured in standardised terms, they are also a demonstration of what Morison enjoyed most about her role; the opportunity to encourage and collaborate with students in acts of serious play.

Alternately blooming and drooping across the gallery wall, Morison’s dark bouquet thrums with subversive symbolism. Size is the first thing you notice. They’re ridiculously big flowers – flaunting the kind of exaggerated dimensions that are used to claim attention, capture the narrative and shake up the usual order of things. So, in part, they’re a work about the politics of scale – that shift in power that comes when you take up space. Now, take another look at that subtitle, ‘Appropriate brushes for large flower paintings’. Read one way, it’s straightforwardly descriptive. As John Hurrell has noted, however, these flower-brushes are also appropriations: objects borrowed from one context and repurposed for another. In this case, floor mops – traditionally associated with housework, especially ‘women’s work’ – have been stiffened and strengthened with fibreglass and plaster to form strange new specimens that reference both the physical and domestic obligations that might suppress women’s creativity and conventional expectations about gender roles. Historically, female artists often suffered from a kind of genre snobbery that dismissed them as mere hobbyists – in an ideal world, ladies quietly amused themselves with delicate flower paintings while real artists wrestled manfully with the landscape outside. The sheer physicality of Morison’s flowers contests the validity of these categorisations, bringing our attention firmly back to the determination and dexterity required to succeed – as Margaret Stoddart and her flower-painting, hill-climbing peers did – in any creative field.

In conventional art symbolism, where tightly budded roses represent chaste, perfect beauty, and dropped petals or aging blooms signal a lack of virtue or desirability, Morison’s blown-out flower heads would be well past their best. Too big to be ignored, they’re now dropping their seeds and passing on their influence to the next generation. The Latin word for flower gave us the term ‘flourish’ in the sense of blossoming or thriving. Later, though, it came to refer to the idea of brandishing – the act of holding something in the hand and waving it about – a weapon perhaps, or even a paintbrush.

Felicity Milburn

Curator

Lisa Reihana Sex Trade, Gift for Banks, Dancing Lovers, Sextant Lesson (18550) (19205) 2017. Pigment print on Hahnemühle paper, mounted on aluminium dibond behind acrylic. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2018

Sex Trade, Gift for Banks, Dancing Lovers, Sextant Lesson (18550) (19205)

The panoramic image of CinemaScope is one of the defining technical achievements of twentieth-century cinema – an accomplishment that marked the medium’s arrival as an independent artform yet had painting and printmaking at its beginning. Artist Lisa Reihana, of Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Hine, Ngai Tu, English and Welsh descent, located her twenty-five metre wide video installation In Pursuit of Venus [infected] (2015–17) in a more Georgian tradition to represent Aotearoa New Zealand at the 57th Venice Biennale in 2017.

In Pursuit of Venus [infected] is a scrolling mise en scène that employs samples from a Georgian wallpaper, Joseph Dufour’s Sauvages De La Mer Pacifique (1804), and composited video of historical narratives and invented tableaux. At 10.8 metres long, Dufour’s original mural spanned a room, looping around as if endless. His depiction of a Tahitian landscape is populated with fifteen representations of the Polynesian and Australasian nations including Māori. All appear Eurocentric. On first seeing the wallpaper at the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra in 2005, Reihana was struck by the cultural conflicts the work raised for her.

… this beautiful but strange object, this wallpaper, and then being told that these were Pacific people. I was completely gobsmacked because I couldn’t see anything that I recognised and I came across the catalogue that Vivienne Webb had written and I suddenly thought, what an amazing idea, to bring a wallpaper back to life!1

The Gallery’s recent acquisition, Sex Trade, Gift for Banks, Dancing Lovers, Sextant Lesson (18550) (19205) (2017) stems from Reihana’s grand work for Venice and reflects a class system directed by males and operating across race and cultures. By representing the historical accounts of specific women as objects for negotiation and trade, Reihana reveals the way in which, regardless of status, they existed within a power structure principally overseen by men.

In responding to Dufour, Reihana provided a cinematic space for Māori, Polynesian and Australasian nations to represent themselves. As a collaborator Reihana was in the background, operating within Barry Barclay’s definition of Fourth Cinema and a Māori philosophy towards filmmaking. With that she demonstrates manaakitanga (kindness), whakawhanaungatanga (connectedness), and rangatiratanga (stewardship).

It could be argued that a tradition of the panoramic exists within te ao Māori arts: some pigment on rock paintings span several metres while the smaller drawings in charcoal often appear in clusters that are reminiscent of Reihana’s various tableaux, and are also part of the landscape.

Kowhaiwhai, another tradition of painting was described by Herbert Williams as being a “painted scroll ornamentation”.2 This is a useful observation for considering Sex Trade, Gift for Banks, Dancing Lovers, Sextant Lesson (18550) (19205) in relation to Reihana’s panoramic moving image. As kowhaiwhai sit within the wharenui, these works might sit within Reihana’s most ambitious project – her digital marae. She continues and expands upon the relationship between Māori arts and architecture from a Māori woman’s perspective.

Nathan Pohio

Assistant curator

Fiona Pardington The Charlotte Jane 2009. C-type photograph. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2009

The Charlotte Jane

Fiona Pardington is a photographer of Kāi Tahu, Kāti Māmoe and Scottish ancestry, a well-travelled artist whose work often opens up paths of discovery for herself and others. While we understand that her finger eventually engages the shutter, we also see regular evidence of her searching for a particular kind of pulse. The work can feel like dreamlike exploration, and the passages taken akin to something like time travel, while also conveying a certain sense of risk. This is The Charlotte Jane.

Farewelling her London home at daybreak on Wednesday 3 September 1850, 27-year-old Mary Ann Bishop gave anguish to paper. “We left Hackney at a quarter to 6 in the morning; to describe my feelings at this painful moment I cannot. I pray that this gigantic speculation of my brothers will not turn to our ruin, and may God give us strength to bear with our tribulations...” At Gravesend three days later, waiting with others of the Bishop family including brothers Frederick, Edward and Charles, she recounted that “we were told to be in readiness as the ships were expected in hourly, and so the moment is coming when I am to bid adieu to England, my friends adieu, may you never know the feeling of an emigrant”. Mary Ann Bishop and others preparing to board the Charlotte Jane were among some 750 people joining the voyage to the ends of the earth on the Canterbury Association’s first four ships; participants in John Robert Godley’s experiment. On Saturday at noon, in Miss Bishop’s words:

I stepped from my native shore, alas, my feelings I cannot describe, better pass over this part as no one on earth can know or fully enter into the conflict and contention of mind I was suffering under, to be thoroughly happy from England I never can as long as memory bears in mind the objection my beloved Parents had to emigration, I thought my heart would break, illness began directly and it was very rough…

The Bishop family, among 154 souls leaving on the Charlotte Jane, were Colonists rather than Settlers, this distinction through their being prosperous enough to be purchase land when in their new situation.3 Along with hopes, all those on board shared some of Miss Bishop’s trepidation and seasickness. Alleviating the boredom and privations of shipboard life, diversions over the next fourteen weeks included natural phenomena such as porpoises, flying fish, spouting whales, albatrosses and storm petrels – sometimes at night sailing through phosphorescence (as Emma Barker recorded three weeks into the journey, “Tonight I have been watching a lovely sight from our clergyman’s stern cabin windows, the sea all in a state of phosphorescence in the run of the ship, resembling a milky way of brilliant morning stars dashing along.”) There were also regular reels and dances and songs; watercolour painting, poetry and sermons; two manuscript weekly magazines (The Cockroach and The Sea-pie); one birth, one marriage, and the deaths of three small children.

A hundred years later, Canterbury’s 1950 centennial year summonsed forth commemorative murals, biographies, postage stamps and exhibitions, along with celebratory film reels and historical re-enactments. Putting his glass blowing skills to a fabulous test, Christchurch man John Rowe’s personal response was to create, in threads of glass, a scale model of the Charlotte Jane, the first of the First Four Ships to berth at Lyttelton; the one that also carried his ancestors. His first completed version is said to have been damaged or lost; his second is now in good care at Canterbury Museum. For Pardington’s eye, John Rowe’s ship was a waiting gift.

Ken Hall

Curator

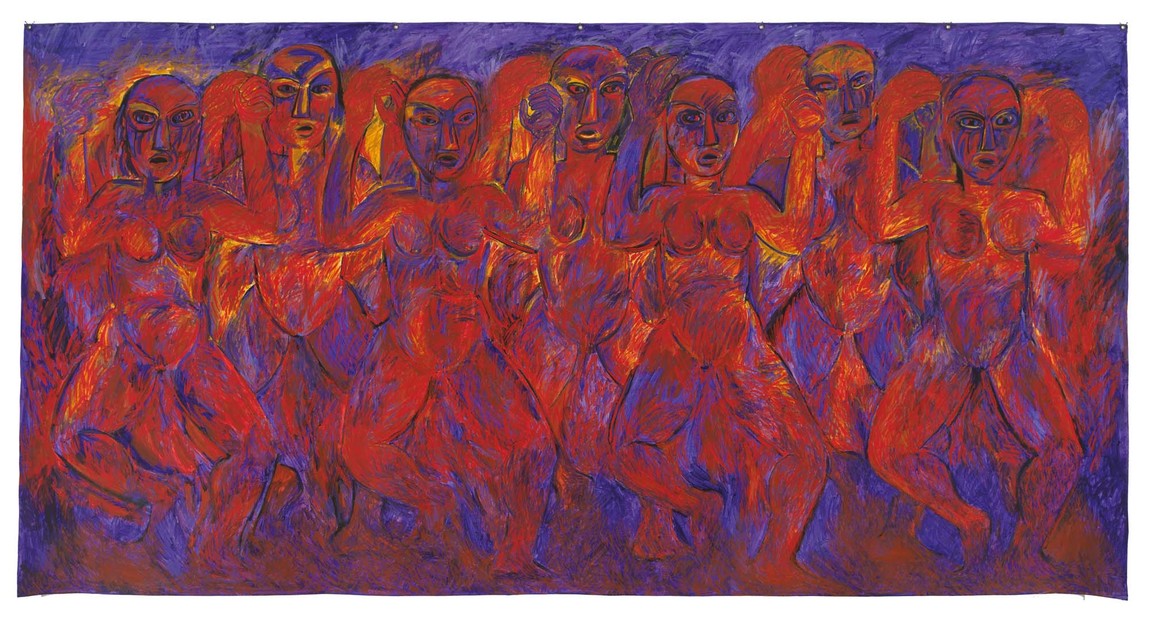

Robyn Kahukiwa Tena I Ruia 1987. Acrylic on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 1989

Tena I Ruia

When I’m thinking about putting together an exhibition, I often look for some kind of anchor point. By that I mean a work that not only asserts its presence in a space but which grounds and challenges my thinking – a place to start from and to return to, again and again. Robyn Kahukiwa’s magisterial Tena I Ruia is exactly that kind of work, a powerful and generative presence in our current contemporary exhibition from the collection, We Do This, which I co-curated with Felicity Milburn. It was one of the first works we confirmed for the exhibition.

Tena I Ruia is a big painting. It’s four metres wide, just over two metres high. It’s on loose canvas, pierced with eyelets, painted in flame red and deep bruised violet with sharp yellow highlights. It’s an assertive physical presence in a room – and that’s before you’ve even got to the subject, which is the depiction of a group of Māori women performing a commanding haka. While most haka are performed by men, some iwi, including Ngāti Porou to which Kahukiwa whakapapas, have significant traditions of female haka. At times, haka have been used by women to articulate their fight for social justice.

We Do This is an exhibition to mark the 125th anniversary of universal suffrage in Aotearoa New Zealand – the moment when women claimed the right to vote. (I always think it’s important to write about it like that, rather than falling into the smug national line that Aotearoa New Zealand was the first country to give women the vote. It took many years of struggle for New Zealand suffragists to prevail in their fight for representation, against trenchant opposition. The right to vote was claimed by women, rather than given to them.)

There’s an extraordinary energy that comes off Kahukiwa’s Tena I Ruia. It’s the energy of seven individual women moving in unison, painted at life size. While the expression and character of the figures are different, each woman has one foot firmly planted on the ground, while the other is raised in the process of stamping vigorously. Their arms are elevated, their mouths are open. They are making sound, taking up space, filling the air, claiming attention. They represent their own message. It’s impossible to ignore them.

Kahukiwa is a hugely significant figure in the expression of mana wahine in the visual arts. She grew up in Australia, and moved to this country as a young woman. Around 1967, noted the late art historian Jonathan Mane-Wheoki, “as a housebound young mother in Greymouth, she succumbed to an impulse to paint.”4 From 1985 she began to draw on traditions of the carved figure in her work, following what she described later as “a significant meeting” with master carver Pine Taiapa’s carved image of her ancestor, Te Aomihia. “My subsequent work,” she said, “has been influenced by the beauty and message of this carving.”FTN5 Tena I Ruia’s figures are derived from the ancestral forms of carving, transformed into two dimensions and metaphorical space through the contemporary medium of paint.

Kahukiwa has stated that Tena I Ruia represents “a form of challenge to Māori and Pakeha to show that we have the drive to self-determination and the affirmation of tangata whenua status.” As a Pakeha woman, I am profoundly grateful for the leadership shown by Kahukiwa and other mana wahine. Her work reaches back into the past and gestures towards the future in which strong women represent themselves. As poet and artist Roma Potiki has said, Kahukiwa’s work offers “a view that helps us reshape the way we look at the formation and importance of identity.”6

Lara Strongman

Senior curator

![Watch 'A conversation with Lisa Reihana [extract]' on YouTube.](/media/cache/99/63/996311ef6e7f2d3da3cbe8f76cb74960.jpg)