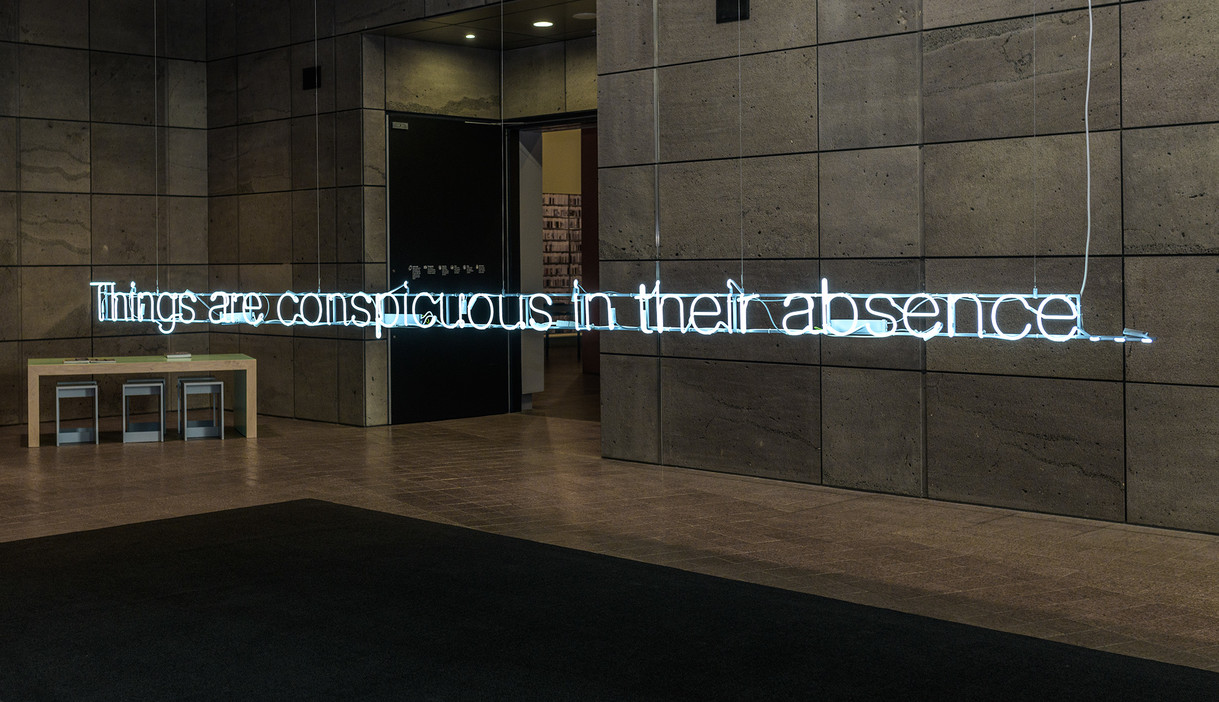

A. Lois White Expulsion c.1939. Oil on board. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2009

Raising the Stakes

On the opening of the Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū Jenny Harper, then at Victoria University Wellington, wrote that the challenge for the newly opened Gallery was ‘to raise the stakes by acknowledging it is no longer the McDougall but is poised to become the force in the New Zealand art scene that Christchurch deserves.’1 When, three years later, she became director of the Gallery, that’s exactly what she set out to achieve on several fronts. One of those was developing the collection.

Harper tells me that, from the outset, she pushed the Gallery’s five curators to look beyond their own portfolios when considering potential acquisitions. She wanted them to think across the collection and about how new acquisitions would speak to existing works, regardless of medium or period.2 This was not a novel idea in art museums here or overseas but for the Gallery it signalled a fresh approach, not only to collecting, but also to exhibition development. Wisely, Harper also proposed to buy fewer but more significant works, a strategy that would take an unexpected turn in years to come.

Another shift, according to senior curator Lara Strongman, has been in the scope of collecting.3 For some time, Strongman notes, collecting by the McDougall and the Gallery had focused predominantly on local artists.4 There are, of course, many notable artists with links to Canterbury but, with other major museums taking a wider purview, this was ultimately a limiting approach and one which Harper and her team sought to address.

Julia Morison Some thing, for example 2011. Metal cage and stand, melted shopping bags, glass, rubber. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, gift of Chartwell Trust 2011

Petrus van der Velden The Leuvehaven, Rotterdam 1867. Oil on canvas. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased with assistance from Gabrielle Tasman in memory of Adriaan and the Olive Stirrat bequest. Purchase supported by Christchurch City Council’s Challenge Grant to Christchurch Art Gallery Trust, 2010

To my mind, this broader approach has been most successful in the area of modern and contemporary art. Major works by New Zealand artists such as Bill Culbert, Fiona Connor, Gregor Kregar, Michael Parekowhai, John Reynolds, Peter Stichbury and Barbara Tuck have been purchased, as have paintings by Frances Hodgkins and A. Lois White. Works by photographers not previously represented – including Gavin Hipkins, Shigeyuki Kihara, Fiona Pardington and Neil Pardington – have been added to the collection along with photographs by younger practitioners. Works by contemporary British artists Susan Collis, Pip Culbert, Sarah Lucas, Tony Oursler and Bridget Riley, and Australians Rebecca Baumann, Callum Morton and Haines & Hinterding have also been acquired.

Close attention is, of course, still being paid to artists with local connections. The N. Barrett Bequest, which is tagged to the purchase of work by Canterbury artists working between 1940 and 1980, has enabled the acquisition of works by Rita Angus, Leo Bensemann, Colin McCahon, Douglas MacDiarmid, Gordon Walters and Albion Wright. Substantial works by senior practitioners and younger artists have been purchased. The Gallery has added to its strong holdings of work by Petrus van der Velden though gift and purchase, most notably the oil painting The Leuvehaven, Rotterdam (1867). Works by moderns Doris Lusk, Juliet Peter and Olivia Spencer Bower have also been acquired. Strongman says she and Harper have been keen to increase the representation of women artists and roughly one third of the artists whose work has been acquired in the last eleven years are women. However, the issue of adequately representing Māori, Pasifika and Asian New Zealand artists is one, I’d suggest, that has yet to be fully addressed.

The Gallery has also received many gifts of works. Such offers need to be carefully considered, balancing alignment to collection policy and priorities with sensitivity towards benefactors. Recent donations suggest the Gallery is an institution that’s responsive to and respected by its community of artists, collectors and art lovers. The most substantial is the Max Gimblett and Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett Gift of almost 200 works on paper and unique artist’s books. There have also been gifts from local artists, including Julia Morison, Pauline Rhodes and Philip Trusttum, as well as the families of Leo Bensemann, John Johns and Carl Sydow.

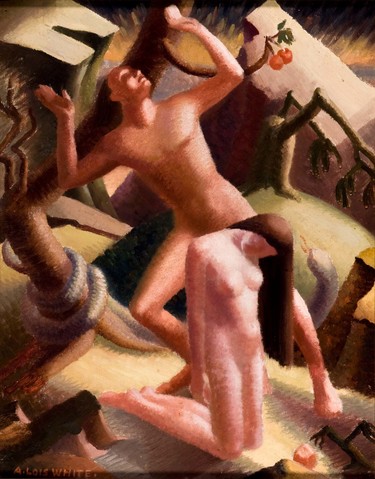

Several gifts were made in response to the earthquakes of 2010 and 2011 and their impact on the Gallery and the city. Most unexpected of all was the contribution by English artist Sarah Lucas, who was installing a show at Auckland’s Two Rooms when the 22 February earthquake struck. She donated the proceeds from sales of her work; Two Rooms and Lucas’s London dealer, Sadie Coles HQ, added their commissions to the gift. This enabled the purchase of works by two young Christchurch artists, while collectors Andrew and Jenny Smith responded by purchasing a work by Lucas for the Gallery collection. A donation from Sheelagh Thompson, to mark her 86th birthday and Harper’s dedication to the Gallery during its closure, resulted in the purchase of works by Fiona Pardington, Shannon Te Ao and Francis van Hout.

Sarah Lucas NUD CYCLADIC 1 2009. Tights, fluff, wire, concrete blocks, MDF. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchase enabled by a gift from Andrew and Jenny Smith, made in response to the generosity of Sarah Lucas, Sadie Coles, London and Two Rooms, Auckland to the people of Christchurch on the occasion of the Canterbury Earthquake, February 2011

Shannon Te Ao Untitled (Malady) 2016. HD digital video file. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, gift of Sheelagh Thompson marking her 86th birthday and honouring director Jenny Harper's dedication to Christchurch Art Gallery during the five years of its closure after the 2010–11 Canterbury earthquakes.

Harper’s resolve to acquire more substantial works for the collection became even more ambitious following the earthquakes. The decision to purchase five high profile works to mark the five years the Gallery building was closed came about almost accidentally following the extraordinary public response to the proposed acquisition of Michael Parekowhai’s Chapman’s Homer. In a restaging of Parekowhai’s 2011 Venice Biennale project his two bronze bulls atop their bronze grand pianos were installed against a background of rubble in central Christchurch. The work was widely perceived as a symbol of strength, determination and the power of the arts to heal and inspire.5 Letters to Christchurch’s Press suggesting the Gallery buy one of the bulls led to a fundraising dinner, a PledgeMe appeal and support from local businesses and individuals. Harper realised that, even with so much else to be mended in their broken city, there were people willing and able to support the purchase of significant works that would be enjoyed for years to come. At the same time, it became clear that the Gallery would be closed for five years in total and so was born the idea of – one might say, defiantly – marking each of those years with a major addition to the collection; as Harper says, ‘collecting is one thing we could carry on doing during that time.’6 Underlying this is the perception that a museum collection signifies permanence, and new acquisitions a belief in the future of the institution and its community – a perception that many in Christchurch must have welcomed.

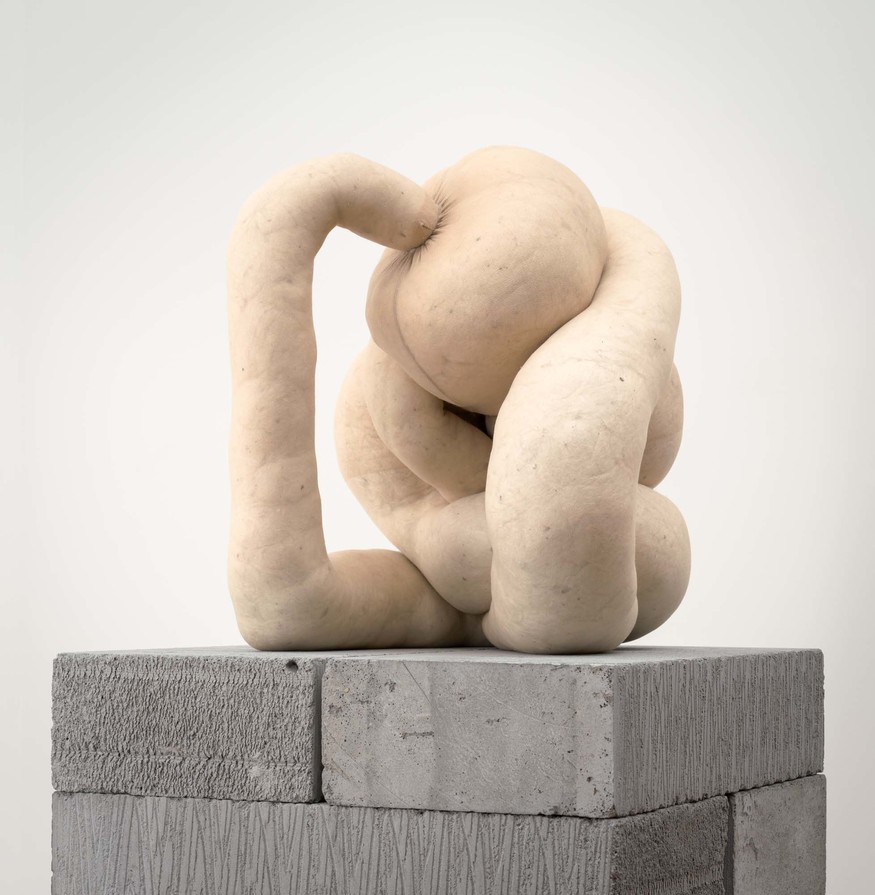

Each of the four other major works has, in its own way, a particular connection with Christchurch. Harper herself has a long relationship with two of the artists and freely admits that the choice of the five icon works was hers, ‘not a committee decision’.7 With its orchestrated jumble of fluorescent tubes and inverted second-hand tables and chairs, Bill Culbert’s Bebop (2013) is a reminder of the turning of so many people’s worlds upside down, here transmuted into a joyful dance of objects and light. Martin Creed’s colourful neon text ‘Everything is going to be alright’ (Work No. 2314, 2015) conveys the hope that one day – although for some that may be a long way off – everything will indeed be all right.

The choice of a work by English artist Bridget Riley was triggered by the purchase of Gordon Walters’s Black on White (1965). At that time Riley was also working in black and white and Harper felt one of those works would create a productive dialogue with the Walters. What transpired, however, was Cosmos, an ordered, tranquil arrangement of soft-hued circles. Cosmos is a wall painting – a collection work that will be on show in its current location for a year or two but can be made anew in future. Like the other three works to date, it occupies its physical territory in a particular way. The Parekowhai now stands proud on the reopened Gallery’s forecourt; the Creed blazes its message from the building’s façade; and Bebop, installed in the foyer, provides a welcome and witty counterpoint to the Gallery’s pompous marble staircase.

The final of the five works will be by Australian artist Ron Mueck, whose eponymous exhibition delighted visitors to the Gallery in the period between the unsettling earthquake of 4 September 2010 and the destruction of 22 February 2011. The intimacy, humanity and compassion of Mueck’s work resonated with the citizens of Christchurch and, for Harper, it seemed fitting to commission a work from him especially for the city. It’s still under wraps…

Colin McCahon There is only one direction 1952. Oil on hardboard. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, N. Barrett Bequest Collection, purchased with the support of Christchurch City Council’s Challenge Grant to the Christchurch Art Gallery Trust 2011. Reproduced courtesy of Colin McCahon Research and Publication Trust

The efforts to raise funds for these and other acquisitions made by Harper, the Gallery Foundation, staff and supporters have been enormous. Many benefactors have been brought into the fold and funds have been raised through gala dinners, auctions and other activities. The Christchurch City Council’s Challenge Grant has for some years matched funding from other sources, up to an annual limit, but – perhaps unsurprisingly in a context with so many financial demands and so much need – the council reduced the Gallery’s core acquisitions fund in 2015. Harper deplored this but, true to form, responded with her own brand of persuasive determination. The shrewd decision to purchase Shane Cotton’s Haymaker series in partnership with the Dunedin Public Art Gallery was another way of stretching acquisition funds. As far as I’m aware, it’s the first such collaboration in Aotearoa and it sets a useful precedent for future collection development.

In her eleven years at the helm of the Gallery, Harper has been clear and increasingly bold in her approach to building the collection. Without the earthquakes and the fortuitous response to Parekowhai’s bulls, would – or could – her ambition have soared so high? It’s hard to say; but she has undoubtedly left Christchurch Art Gallery the better for it.