It is in that inch that we all live

Jamie Hanton writes on the collegiate art collections of Canterbury.

Ria Bancroft and Pat Mulcahy Energetic Forms 1965–66. Collection of Macmillan Brown Library and University of Canterbury. Reproduced with the permission of Peb Simmons and courtesy of the Macmillan Brown Library and University of Canterbury. Photograph Laura Dunham

‘People do get attached to works of art; perhaps even unreasonably attached.' 1 When Dr Peter Gough began at the University of Canterbury as Lecturer in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering in 1980 he may not have predicted that thirteen years later he would be called on to assuage an inter- departmental stoush—Chemistry vs. History—over a hotly contested Peter Ransom drawing.

Graham Bennett Oversight 2012. Collection of Lincoln University. Reproduced courtesy of Lincoln University

As Chairperson of the Art Purchases Committee there is no doubt that Dr Gough's use of the phrase 'unreasonably attached' was not delivered flippantly, but in a knowing manner that acknowledged the strong feelings that works of art can provoke in their audiences. The problem of such territorial ownership—if the overwhelming desire of two different parties to be close to an artwork could be called a problem (most curators, gallery directors, and fundraisers would say not) is quite distinct to university collections.

The three largest tertiary institutions in the Canterbury region: the University of Canterbury (UC), Lincoln University, and Christchurch Polytechnic Institute of Technology (CPIT) all hold significant art collections which provide their audiences with daily art encounters. CPIT has just under 400 items, Lincoln's collection has 280; and prior to its amalgamation with the University of Canterbury, the Christchurch College of Education held its own significant collection of art, which is now administered by UC whose total collection numbers close to 5,000 works. While each of these tertiary art collections has a unique history, they are united by the fact that they are not museum collections. They do not have a dedicated space for display or exhibition and they are not required to act as the public record of the day as public galleries and museums are. This lack of expectation creates a certain freedom, but with this freedom comes a longing and searching for a recognisable identity and purpose.

The artworks in the University of Canterbury Art Collection, like most university and college art collections, were not acquired with a clearly focused collecting strategy but were rather accumulated over the years in a somewhat arbitrary manner by various departments, individuals, and by purchase and gift. Departmental collections reflected specific aesthetic and research interests. The consolidation of the university's 13 sub-collections under a single administrative unit is a relatively recent phenomenon, which occurred with the establishment of a Collections Registrar in 2004. 2

In James Hamilton's influential article, 'The Role of the University Curator in the 1990s', the author proposes that the four most common roles performed by university collections are ceremonial, commemorative, decorative, and didactic. 3 Until the formation of the University of Canterbury Art Purchases Committee (APC) in 1988, the great majority of art purchasing within UC was commemorative, via the commissioning of portraits of distinguished professors and Vice-Chancellors. Hamilton goes on to say, 'It is the existence of the final didactic category that pays the University Curator's salary . . . it is the management of the evolving balance between the decorative and the didactic that will keep the various collections in the curator's charge active and relevant. There may only be an inch between the 'decorative' and the 'didactic', but it is in that inch that we all live.' 4

If we use Hamilton's language, we could say that the Art Purchases Committee was addressing the inch between decorative and the didactic, when in the original terms of reference for the group they state: 'The function and responsibility of the committee will be to see that the university appropriately and adequately fulfils its role of providing a cultural and intellectual education for all its students especially with respect to the visual arts by the judicious purchasing and display of work to improve the cultural and physical environment of the University with the best, and most challenging and inventive examples of recent developments in the arts.' 5

The language used above, and in other contemporaneous documentation, is indicative of the era towards the end of peak art education in primary, secondary, and tertiary institutions—where the dominant discourse centred around the provision of a widespread and inclusive visual literacy. The cultural landscape—nationally and internationally— underwent a shift in the 1990s as neo-liberal financial doctrines and output and result-based policies became entrenched. At UC at least, this was not felt financially. The Art Purchases Committee saw over a decade of year-on-year budget increases for acquisitions. This was due in large part to the strength of the personalities operating at the time—including Julie King and Riduan Tomkins—and campus-wide buy-in for the programme. New acquisitions were displayed at the end of each year, and departments were able to bid via votes for the work they most desired. There were however pushes to extend the use of the collection beyond its primarily furnishing nature. Jonathan Mane-Wheoki—nominated buyer for the APC for half of the decade—argued against the additional demands on the collection and its voluntary committee in favour of adhering to the committee's stated purpose as purchasers of art rather than curators. An avid supporter of artists and their ongoing development, Mane-Wheoki was responsible for some of the most prescient purchases completed by the committee, buying early Shane Cotton and Séraphine Pick pieces. He also sought to expand the APC's remit from easy-to-hang framed works on paper to larger, more ambitious pieces in a range of media including a suspended Neil Dawson sculpture and a pair of mirror-tile-encased wall-hung Richard Reddaway figures, as well ensuring the collection represented Māori practitioners working in traditional Toi Māori.

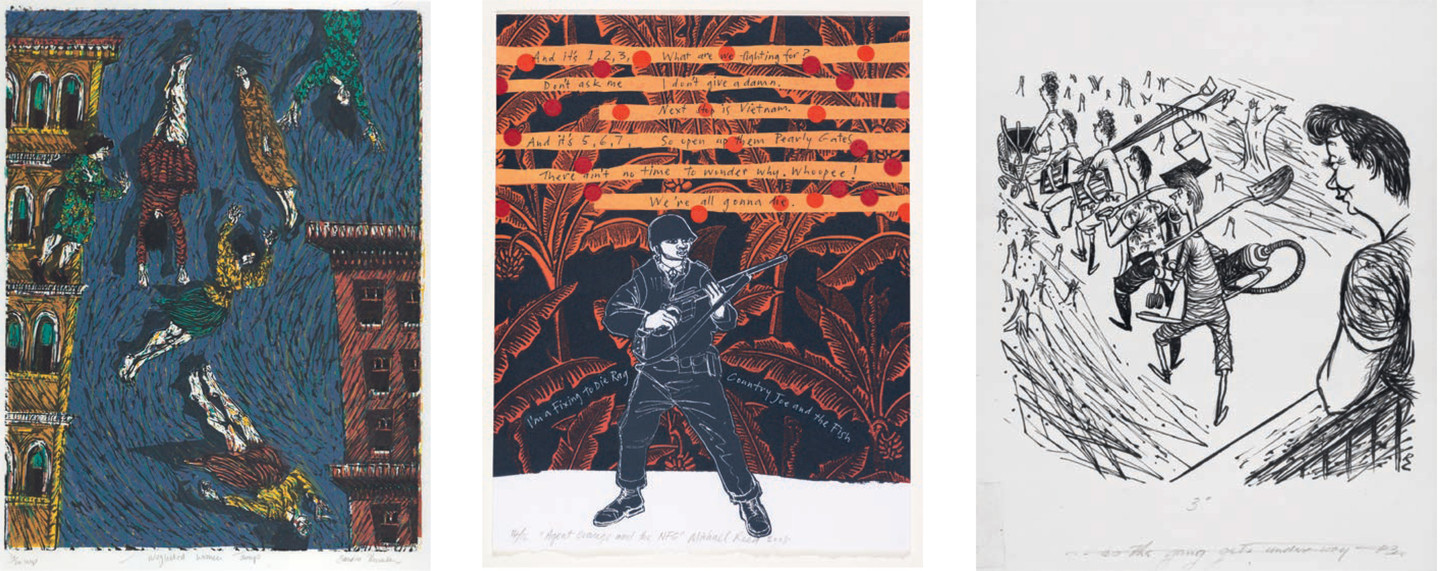

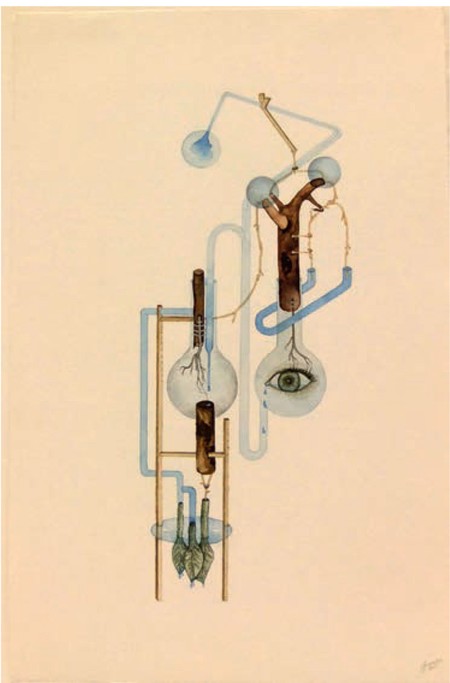

However, as the collection grew, its support structures, both human and physical were stretched. This process of organic growth 'parallel to the core business of research and teaching' 6 is a common feature of tertiary collections, and arguing for further resources including increased storage and professional care often means re-aligning the collection towards more measurable outcomes. This potential re-alignment taken to its logical conclusion raises a number of important questions: when does the purchasing of art become over indebted to pedagogical directives rather than providing broader campus benefits? How should the teaching aims of the various departments be balanced? Current methods of using existing collection items across a range of disciplines at CPIT, Lincoln and UC prove that a balance between the decorative and the didactic can be achieved. These approaches draw on diverse subject matters to achieve a variety of pedagogical objectives. At CPIT a number of artworks are used in the teaching of social work; Sandra Thomson's Neglected Women Jump and Michael Reed's exploration of the issues surrounding the Vietnam war and nuclear testing are used to demonstrate the way in which art has historically been used to advocate for social change. At UC Russell Clark's collection of illustrations for the New Zealand Listener of quotidian Kiwi life and Juliet Peter's depiction of land girls working in a rural setting are regularly used in teaching New Zealand history. In Fine Arts, Zina Swanson's intricate watercolours are used in classes relating to expanded drawing techniques, and in Art History and Theory Nathan Pohio's experimental cinematic photographs are used alongside Liyen Chong's embroidered hair work in the examination of medium and materiality. At Lincoln University artworks from the collection are utilised in the teaching of Cultural Landscape in the disciplines of landscape architecture and design. Bill Sutton's Plantation Series XVIII provides a strong example of the way falling light and topography combine to create a powerful landscape, whereas Graham Bennett's recent sculpture Oversight created as Sculptor-in-Residence is a more direct lesson in physicality and scale.

Sandra Thomson Neglected Women Jump 1988. Linocut. Collection of CPIT. Reproduced courtesy of CPIT Artwork Collection and the artist

Michael Reed Agent Orange and the NFG 2008. Screenprint. Collection of CPIT. Reproduced courtesy of CPIT Artwork Collection and the artist

Russell Clark As the gang gets under way 1955. Indian ink on paper. Collection of Macmillan Brown Library and University of Canterbury. Reproduced with the permission of Rosalie Archer and courtesy of the Macmillan Brown Library and University of Canterbury

Zina Swanson Untitled No.1 2010. Watercolour. Collection of Macmillan Brown Library and University of Canterbury. Reproduced with permission of Zina Swanson and courtesy of the Macmillan Brown Library and University of Canterbury

One of the more contentious issues around the development of tertiary collections is the place of student artworks. Arguments against collecting student work often cite the preservation of the overall level of quality and prestige of the collection as key factors; that in purchasing student works it is difficult to discern a future pedigree of artist at such an early stage. There is, however, a precedent dating back to the Canterbury College School of Art of student work being integrated into the collection for display and future use as exemplary models via examinations, scholarships, and awards. Changing modes of teaching at the School of Fine Arts along with changing disciplines and an ongoing increase in students meant that collecting student work became impractical. In 2009, the Art Purchases Committee at the University of Canterbury agreed to dedicate a certain amount of its annual acquisitions budget to purchase outstanding work completed by graduating students through an annual competition and exhibition, SELECT. In 2013, in an EyeContact review of the SELECT exhibition, Keir Leslie argued that selecting for 'the best, the most stimulating, and the most inventive' unfairly privileged certain kinds of practice over others.' 7 In the academic arena, where objective merit is arguably the highest value held, a competition like SELECT is bound to be problematic, as would any competition which relies on the subjectivity of an external judge. Some of the arguments above can be countered by the fact that the beauty of a university collection is its ability to reveal other histories, rather than solely create and perpetuate an art historical canon based on individuals. The School of Fine Arts sub-collection, from the late 19th century to the middle of the 20th century captures the historical shifts in studio disciplines through its active collecting of staff and student artist models. These works from Arts and Crafts embroidery and printmaking, silversmithing, and calligraphy are now invaluable and reference a social and political heritage, as well as an artistic lineage.

This transportive potential lives in the hallways and public spaces across campus and provides daily encounters that, at one end of the spectrum can provide a moment of brightness, and at the other end can change the way one looks at the world. A simple one-page unsigned report written about the Christchurch College of Education Art Collection on the occasion of the latest acquisition in 1966, a Doreen Blumhardt pot, perhaps captures this William Morris-esque belief best. 'These works help to make the precincts of the college more interesting and provide a starting point for stimulating discussion. Students are encouraged to develop discrimination and good taste concerning the aesthetic aspects of their environment so that when they leave college they are able to hold informed opinions on the many aspects of design in the community at large.'

These sentiments are brought into even sharper focus given the current environment in Christchurch, where much of what was held dear has gone and we are now left to decide how to proceed. The Ria Bancroft and Pat Mulcahy collaboration, Energetic Forms once located in the Science Lecture Theatre Building at the University of Canterbury becomes poignantly emblematic of this; its heroic presence emphasised by its absence. If there ever was a time to become 'unreasonably attached' to a work of art, it is now.

Jamie Hanton Art Collections Curator, University of Canterbury

Sincere thanks to Julie Humby of CPIT, Dr Jacky Bowring of Lincoln University, and Max Podstolski from the University of Canterbury.