Andrew Barber The Sea 2013. Enamel and acrylic paint. Installation view, A world undone, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki November 2014 – April 2015. Chartwell Collection, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, Auckland, New Zealand

A gymnasium for the mind

Sue Gardiner discusses the Chartwell Collection

Who would have thought New Zealand's first dating game, Computa-Pal, was a fundraising idea to support the visual arts? Ahead of its time, the project demonstrated the kind of creative thinking that eventually led to the development of the Chartwell Collection of contemporary New Zealand and Australian art.

Computa-Pal was a punch card system matching couples, using data collected from questionnaires. It was developed in the early 1970s by my father Robert Gardiner, CNZM, who was then a Hamilton businessman and accountant. As well as being a fundraiser for a newly established Hamilton Art Gallery Trust, it successfully married our family babysitter to her Computa-Pal match.

This Trust was formed to support and raise funds for the development of a new public art gallery for the city. Gardiner recalls: 'I was on the Waikato Society of Arts Acquisitions Committee, became interested in growing the Society's Collection, and later was an inaugural trustee of the Gallery Trust, advocating for a new Hamilton Art Gallery building.'

While the city art community waited for the newly named, purpose-built Waikato Museum of Art and History to be realized, it operated in temporary premises in London Street, Hamilton. About this time, his Computa-Pal match-making days coming to an end, Gardiner established the Chartwell Trust to further assist the visual arts. The first Chartwell Collection acquisitions of contemporary art were made under the auspices of this new independent charitable trust.

Gardiner remembers the early days. 'The Collection was named after the suburb our family lived in and was established as a privately managed public collection on loan to the public gallery sector. It was maybe a new model for its time in New Zealand, and still continues today—41 years later.' Reflecting on the Chartwell Collection's private/public foundation, he recalls that it was conceived to operate well beyond his lifetime, noting: 'From day one all acquisitions went immediately into public gallery care and use, being available for loans. I have maintained a close relationship and empathy with the professional ambitions of public art galleries in New Zealand and I increasingly became interested in their governance and collection activities.'

In writing Chartwell's first acquisition policy, Gardiner says, 'We looked to complement the Waikato Museum's existing public collection, so early acquisitions were closely matched to their focus on prints at the time.' The first Chartwell acquisitions were a group of ten prints and works on paper acquired during a visit in April 1974 to Mildura and Melbourne with Campbell Smith, Director of Fine Arts at the Waikato Museum. These Australian artworks included silk screen-prints by Alun Leach-Jones and John Coburn.

These works were quickly joined by other acquisitions in 1974 and 1975 by key contemporary New Zealand artists: William Sutton, Pat Hanly, Michael Smither, Gordon Walters, Phillip Trusttum, Robert Ellis, Gretchen Albrecht and two artists with strong Waikato connections, Mary McIntyre and Margot Philips. Between April 1974 and December 1981, Chartwell acquired 80 works, including works by Colin McCahon and Ralph Hotere, as well as a number of small works by local artists.

Andrew Barber The Sea 2013. Enamel and acrylic paint. Installation view, A world undone, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki November 2014– April 2015. Chartwell Collection, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, Auckland, New Zealand

'You see the artwork, the work shapes you and you become possessed by it as you try to enter the mind of its maker and the moment of its creation.'

Gardiner takes up the story. 'Around that time, Ken Gorby, then Director of the Waikato Museum, asked me to remove the Collection as there was not enough storage room.' The Chartwell Trust purchased the ex-Hamilton Hotel Buildings at the south end of Victoria Street on the bank of the Waikato River, and converted them into the Hamilton Centre for Contemporary Art (CFCA) and Left Bank Theatre. The CFCA may have been New Zealand's first privately funded public contemporary art gallery and the Chartwell Trust presented 134 contemporary exhibitions in the space over the next 14 years. Many ground-breaking projects with artists from New Zealand and Australia were developed and the Collection was stored in state of the art facilities on site.

Agreements with exhibiting artists provided that any purchase enquires would be referred to the artist's dealer. This encouraged significant private dealer gallery support for the growing Collection, important for a Hamilton-based project, and important relationships with private dealers in distant cities in Australia and New Zealand were developed. Gardiner says, 'The endeavour to understand the nature of art and its benefits was an important and rewarding motivation for me.'

As visitors came to visit the CFCA from far and wide, respect for the project grew. Sue Crockford was a great supporter. She wrote to Gardiner in 1985, saying, 'What you are doing—gathering a major collection—is a very real, positive commitment to New Zealand contemporary art.' After visiting Chartwell Collection Viewing 1985, an annual presentation of works, which included new Australian acquisitions, Crockford noted the excitement of seeing New Zealand work hanging alongside Australian contemporary art—something she hoped would develop more in other institutions in the future. Writing in the exhibition catalogue about the emergence of Australian work in the Collection, Gardiner recognised: 'There is a need to increase New Zealanders' knowledge of Australian art.' That 1985 collection viewing also exhibited sculptures for the first time, reflecting a change in the collecting policy.

In 1987, Chartwell acquired the first of many works by Aboriginal artists, an aspect of the collection policy Gardiner felt strongly about, recognising the opportunity to reveal interests explored by indigenous artists in both countries. Few New Zealand collections were buying art in Australia at the time.

By the 1991 annual Chartwell Collection exhibition, works by major Australian-based artists such as Tony Tuckson, Sidney Nolan, Charlie Tjungurrayi, Davida Allen, Rosalie Gascoigne and Ian Fairweather were being shown alongside those by Richard Killeen, Jacqueline Fraser, Tony Fomison, Milan Mrkusich, Greer Twiss, Billy Apple, Jeffrey Harris and Stephen Bambury. One visitor wrote of his excitement after a visit to Hamilton, saying, ‘I left with adrenalin coursing through my system and a head full of ideas!’ The CFCA was having far reaching consequences for the visual arts and their place in society.

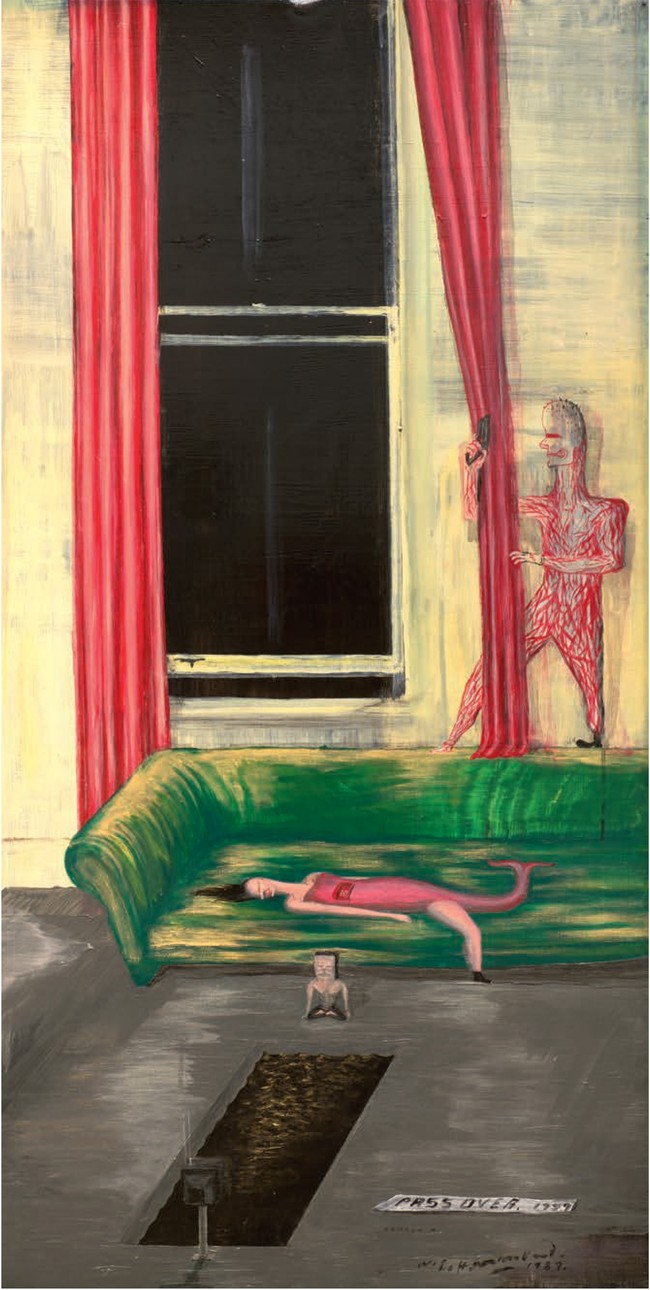

W.D. Hammond Passover 1989. Acrylic and varnish on aluminium, 1200 x 613 mm, Chartwell Collection, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, Auckland, New Zealand

The Collection grew substantially from 1982 to 1994, as Gardiner travelled regularly to view potential acquisitions and undertook sustained reading and study. More than 300 works were added to the Collection. Major acquisitions included works by Julian Dashper, Bill Hammond, Michael Parekowhai, Richard Killeen, Jacqueline Fraser, Don Driver, Peter Peryer, Neil Dawson, Andrew Drummond, John Reynolds and a large group of Australian works by artists such as Judy Watson and Janet Laurence.

The CFCA days were pre-email, so Gardiner's fax machine ran red hot as he corresponded with art professionals the length of the country, while receiving slides and photographs, and loan requests for works to travel beyond Hamilton. Gardiner remembers, 'There was a lot of active thinking and making, exhibiting, meeting artists and gallerists in New Zealand and Australia, analysing ideas, considering creative thinking in art making and the social, historic, cultural and political issues around the visual. Much of this theoretical study contributed to assessments of the cultural value of artworks entering the Collection.'

The new Waikato Museum of Art and History building finally opened in 1987 with Bruce Robinson as Director. With curators Linda Tyler followed by Lara Strongman, he immediately began to work with the Chartwell Collection. By 1993, the Collection had once again become fully integrated into the Museum under a loan agreement, with final Hamilton Centre for Contemporary Art exhibitions held in 1994.

A few years later, in 1997, the Collection was placed on long term loan at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki. In an unpublished interview with Alexa Johnson in 1997, Gardiner talked more about his collecting processes saying, 'All the time I have felt the need to keep an open learning mode in place. You see the artwork, the work shapes you and you become possessed by it as you try to enter the mind of its maker and the moment of its creation. The artist is putting the work out in the world and giving you the opportunity to access the process of its creation as best you can. By keeping on doing that, you are, in your own way, creating something—the cumulative experience of seeking to engage in the creative processes involved.'

The Collection's growing significance at this time was demonstrated by the inclusion of a Chartwell work by Australian artist Emily Kame Kngwarreye at the Australian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 1997. A major Samoan tapa cloth was also acquired that year, and the Collection's first video work, by Yuk King Tan, was acquired in 2001. Recently the Collection's long term commitment to the practice of Australian artist John Nixon was recognised with a generous gift by the artist of more than 45 works, joining other gifts by artists to the Collection.

Now with more than 1500 works and loans to institutions around the world, the Collection has been the subject of several recent exhibitions including As Many Structures As I Can, curated by Emma Bugden at the Dowse in 2013, Made Active, curated by Natasha Conland in 2012 and A world undone, curated by Stephen Cleland at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamāki, in 2014. This exhibition was unusual in that it profiled, for the first time, some of the international acquisitions that have been achieved in recent years, most notably a significant sculpture by Chicago based Jessica Stockholder.

Researching the Collection, Stephen Cleland highlighted Gardiner's unwavering curiosity that has underscored such sustained and focused collecting. In 2001, the then Director of Auckland Art Gallery, Chris Saines, CNZM, wrote about the unique freedoms associated with the Chartwell collecting model. He explains this has created a collection that, 'Positively crackles with points of difference from every other institutional and major private collection in New Zealand . . . Chartwell is simply not and never has been more of the same . . . the collection has become an effective diagnostic of art's prevailing condition.'

Jessica Stockholder A – H 2013. Ladder, number 5 brass, grey plastic toy modules, yard, string, green electrical cord, ochre Plexiglas, rope, acrylic paint, fake fur, cardboard angle, cable ties, TV mount, white hook, yellow tacks, 2146 x 686 x 1245 mm, installation view, A world undone, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, November 2014–April 2015

Gardiner has long viewed the Collection as a collection of ideas. In addition to its cultural functions, each art work demonstrates the practice of creative visual thinking by the artist. 'I have come to believe in the value and potential of contemporary art in developing general creative thinking processes, together with enhanced life experiences. Primarily, there is a belief in the power of the ideation processes involved in both making and viewing art and there is a conviction that the sense-activated imagination needs to be more widely valued.'

Viewing the Collection then as a place where ideas are directly experienced, the works offer opportunity for an engagement, through intuitive sense based thinking, with the creative visual thought processes involved. Gardiner reflects, 'If the domain of art, and of collecting, is an exercise space for the senses and the imagination, then it follows that the public art gallery is a gymnasium for the mind available to all who visit. There, we can access a community's creative capacity within an aesthetic context, and through an understanding of the processes of making by the artist and perception by the viewer, we can enable a deeper understanding of self and the world.'

Earlier this year Gardiner wrote: 'I believed when Chartwell started and still do that there is not enough general political and communal understandings about contemporary art, its nature and role in building a culture with its potential for fulfilment for a nation and its citizens.'

Sue Gardiner is the Co-Director of the Chartwell Collection and a trustee of the Chartwell Trust. The Chartwell Collection is on long term loan at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki.

Collection store — Louise Pether, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, 2010