B.

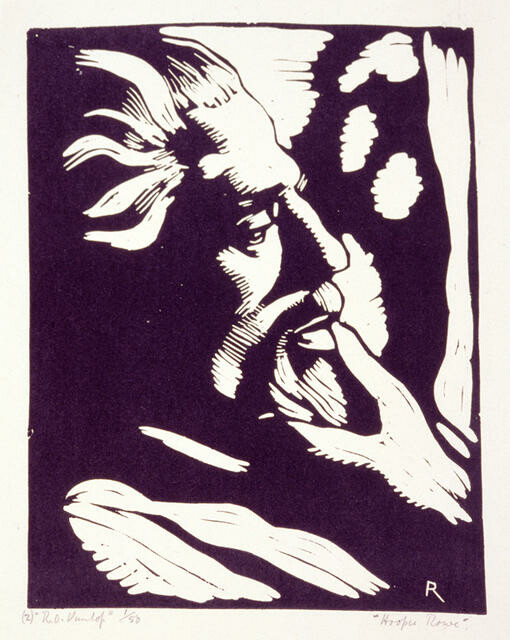

Ronald Ossory Dunlop (left) and Clifford Hooper Rowe (right). Kindly supplied by the Cliff Rowe Estate and reproduced with permission.

Cliff Rowe

Collection

Gallery staff were able to research some of the works in our collection while we were locked down.

Visitor host Alison Brownie, whose face will be familiar on our front desk, looked into the life of Cliff Rowe, artist and lifelong man of the political left. The trail led to his daughter, Anna Sandra Thornberry, who kindly helped us to fill in the gaps in our knowledge of Rowe's biography. Among the treasures made available to us was this photograph of Rowe with Irish artist and author Ronald Ossory Dunlop, the subject of one of the works by Rowe in our collection. Both men exhibited at the Redfern Gallery in London, from which of course our linocut came.

Joe Thornberry from the History Department at Lancaster University is researching Rowe and has written these notes for us:

Cliff Rowe and R O Dunlop first met at Wimbledon College of Art, where they studied under the landscape artist A J Collister. Although a traditionalist, Collister encouraged his students to experiment in their painting, and this formed the basis of the Emotionist Group founded by Rowe and Dunlop in 1923. ‘Emotionism’ was a rather vague philosophy which stressed the primacy of emotion over intellect in the production of art. The Group sought to embrace all forms of art and included, among others, the artist and actor Jean Shepeard, the poet and actor Peggy Ashcroft, and the poet Phillip Henderson. They produced two issues of a magazine called ‘Emotionism’, with Rowe providing a linocut for the cover of the first issue.

In 1927 the Group opened the Hurricane Lamp Gallery in Cheyne Walk in Chelsea (the photograph above of the two cheerfully dishevelled artists was taken shortly after the opening). Among the many members of the London art world who regularly visited the Hurricane Lamp was the director of the Redfern Gallery, Rex Nan Kivell. Through his support Dunlop and his colleagues achieved a wider audience for their work and by 1929 he and Rowe were exhibiting in the Redfern’s Summer Salon alongside the foremost of contemporary British artists. However, the Hurricane Lamp was not financially viable and by 1931 the two artists’ paths had sharply diverged. Dunlop was on his way to becoming an established artist and a Royal Academician. Rowe faced unemployment and poverty, and was eventually to join the British Communist Party.

We are extremely grateful to the family of Cliff Rowe for supplying all this information and helping us to understand a little more about a work in our collection.