B.

Untitled (Taylors Mistake) by William Sutton

Collection

This article first appeared on Stuff as 'Modernism by motorbike' on 28 June 2016 and as 'Artist stumbled upon striking scenery on morning motorbike rides' in The Press on 30 June 2016.

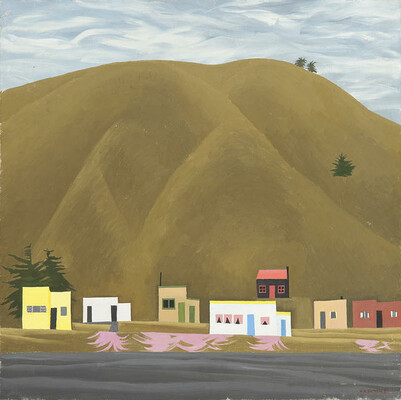

I'm fascinated by Bill Sutton's Untitled (Taylors Mistake). It's a glorious, strange, heart-lifting oddity of a painting that comes from a period of great creative experimentation by the artist (and was held on to by him, though I don't think he ever exhibited it: it came to the Gallery from his estate). The upper half of the work, with a broad ochre sweep of hillside and the swirling grey-blue maelstrom of sky, anticipates Sutton's series of increasingly abstracted Canterbury land- and skyscapes from the 1970s. The lower half of the painting, with its charming frontal depictions of baches at Taylors Mistake, resonates with his country churches painted throughout the 1950s. It's as if the creative preoccupations of two separate decades have been brought together in this work.

When Sutton returned to Christchurch in 1949 after two years studying art in Europe, his work changed markedly. He saw clearly that his own teachers, themselves trained in England, had taught him how to paint the New Zealand landscape in an English manner. He set out to explore a different approach to painting which aimed to capture the underlying structure of the local landscape. Initially he rode a Matchless motorbike up into the Canterbury foothills in search of painting sites; by 1956 he had upgraded to a BSA Golden Flash, which he regularly rode out to Banks Peninsula in the early morning before a day's teaching at the art school. Untitled (Taylors Mistake) is likely to have been conceived on one of these trips: modernism by motorbike.

This part of the coast has long been popular with artists, from Rosa Sawtell to Bill Hammond. It's essentially quite wild, but relatively easy to get to. Sutton painted nearby Boulder Bay in a watercolour in 1945. Twelve years later in Untitled (Taylors Mistake) he turned his back to the ocean and focused his gaze inland, standing at the water's edge with his back to the sea. The upper half of the painting reveals Sutton experimenting with the restricted palette that he would go on to develop in later works. "I've had intimate acquaintance with the Canterbury landscape," he said in an interview in the early 1980s, "and it all comes down to grey and yellow ochre in the long run. We have no other colours." The furrows of dark grey sand at the lower edge of the painting echo the striated clouds at the top: the line of baches, reduced to the simplest of box shapes pierced by doors and windows, stretch across the image in a lively ribbon.

Coming back to Christchurch had been something of a culture shock for Sutton, but his first strong impressions of the New Zealand landscape on his return home ("the smallness and newness of everything") continued to reverberate in his work for the next decade. While later paintings are almost entirely empty of human construction, buildings frequently appear in his works of the 1950s, where their essential provisionality—"wooden and sheet iron Gothic", as Sutton described the country church buildings—is juxtaposed against the harshness of the landscape.

You don’t get an architecture much more provisional than the historic baches at Taylors Mistake. These tiny dwellings caught between the land and the sea have been beset both by the elements and district authorities for more than a century. Sutton's unusual painting speaks of the fragility of our built heritage and the implacable strength of the landscape on which it stands.

![Untitled [Te Onepoto/Taylors Mistake]](/media/cache/31/9e/319e89714e43570f7c3ed8ad96db9557.jpg)