B.

Time, memory, photography

Behind the scenes

As part of the recent Word Christchurch Writers and Readers Festival, Christchurch Art Gallery was a partner in the presentation of 'Remembering Anzac', a session which paired photographic artist Laurence Aberhart with historian Jock Phillips.

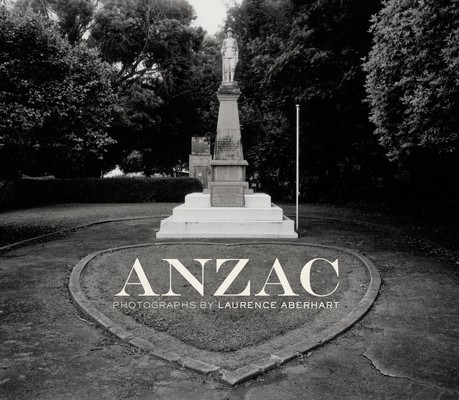

The session was chaired by Christchurch Art Gallery director Jenny Harper. The catalyst for the conversation was Aberhart's book Anzac, which collects together seventy of his photographs of public memorials to those killed in the Great War of 1914–18. Anzac was recently published by Victoria University Press and Dunedin Public Art Gallery, and features a foreword by Phillips.

'Remembering Anzac' was a rare opportunity to hear Aberhart speak in public about his work. He began by observing that he usually objects to subject matter being the topic of conversations about photography, but added that in the case of the war memorials it's appropriate. The book includes images taken by Aberhart between 1980 and 2013 in New Zealand and Australia. 'My modus is I go out there and take photographs of things. And after three or four decades I realised I'd accumulated a body of images that were subject matter,' he said.

Laurence Aberhart and Jock Phillips: Remembering ANZAC. At WORD Christchurch, Christchurch. Sunday 31 August 2014. Photo by Lisa Stanger. From the collection of Christchurch City Libraries

Aberhart's book, said Jock Phillips, is a record of a time when interest in our war memorials waned. The memorials are frequently obscured by foliage or later building: lonely sentinels stand in windswept long grass or are isolated in the centre of a roundabout. Aberhart described one rural memorial which had literally disappeared inside a giant blackberry bush. 'I used to think,' he said, 'that war memorials were a permanent thing. But those of you who have been through earthquakes know that nothing is permanent.'

The war memorials, said Phillips, initially functioned for family and friends at home 'like a surrogate tomb'. The soldiers who fell in battle were all buried overseas, and the memorials provided a place to mourn specific people. Gradually, however, the deaths they commemorated passed beyond living memory.

Phillips pointed out that the typical memorial image of the lone soldier was at odds with the culture of WWI, where the essence of the New Zealand experience was mateship. I was fascinated to learn that many of the soldier figures in small New Zealand towns were ordered from Italian stone masons' catalogues: there were only four or five New Zealand sculptors commissioned to produce these representations.

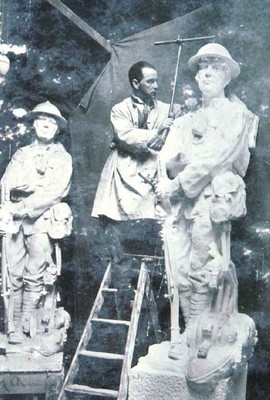

Among these local artists was the Christchurch sculptor William Trethewey (1892-1956), who carved the Kaiapoi Memorial using a local returned serviceman as a model. Less idealised than many of the heroic-type memorial figures, Trethewey's statue depicts the soldier at rest after a charge, festooned with battle gear and weary but resolute. (Trethewey was also the sculptor of the Citizens' War Memorial in Cathedral Square, the marble statue of James Cook in Victoria Square, and the bronze sculpture depicting Kupe on the Wellington waterfront.)

Using a pantograph (the rods are visible around the head of the marble figure at right) William Trethewey copies details from the smaller plaster model to the larger sculpture. Photograph: Canterbury Museum

While the memorials of WWI were community-funded, the post-WWII New Zealand government offered a subsidy for war memorials with a practical community focus. This resulted in a substantial building programme for memorial halls and swimming pools in small towns throughout the country, many of which are still in use as community facilities. Aberhart's work documents the changing relationship between communities and their memorials: it depicts memory as a fluid thing constantly in a process of being reinterpreted rather than as something fixed in time. 'History,' commented Jenny Harper, 'is always being reworked by different generations.'

In answer to a question from the floor about why he uses black and white photography, Aberhart commented that silver nitrate on good-quality paper will last more than 160 years. 'This is proven. Any other [photographic] process is unproven and may not last. I want to make something that will last.'