Crunchify Object

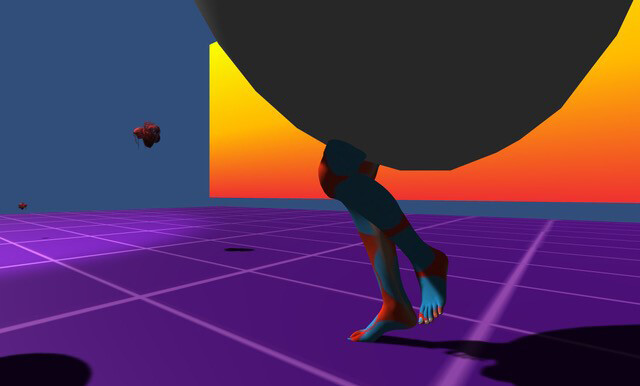

Judy Darragh and Sean Kerr In Kahoots (installation view) 2019. Multimedia installation, sound, projected image, Realtime 3D, LED, mirror wall. Courtesy of the artists and Two Rooms, Auckland. With thanks to The University of Auckland Te Whare Wānanga o Tāmaki Makaurau. Photo: Sam Harnett

}

return a;

}

<crunchifyObject.

G[i,j]= network connectivity matrix.

Culled from the image search “algorithms”, it is unlikely that the unconnected fragments of code above could manifest an output, but I cannot be entirely sure.

What about the following stanza from an untitled poem:

An open space between awaiting speed,

And looking at divine velocity.

A faceless nation under constant need,1

Did a machine trained to recognise and reproduce word patterns through complex algorithmic code write this, or was it a human-nature-digital assemblage?

Where might the divine velocity of computational speed that propels faceless nations to willingly provide Big Tech with oceans of data take us?

Who are we in cahoots with?

What experiences will you have, or have you had, in Judy Darragh and Sean Kerr’s In Kahoots? What did your body trigger when it encountered the sensors that bounced light and data to receptors, coded to create endless variabilities until hardware breaks, electricity ends, or AI algorithms destroy the scenarios (wittingly or unwittingly). Which character or recurring object from Darragh and Kerr’s sculptural lexicon did your shadow interact with? Who were you in cahoots with?

These opening fragments are pointing index fingers (rather than pink inflatable middle fingers) that indicate some of the many layers and interconnected themes operating in Darragh and Kerr’s collaborative work. These index fingers include AI algorithms, machine learning, data mining, extractivism,2 Big Tech, complexity and chaos, and connection and polarisation in our era of surveillance capitalism. These fraught dialectics, which hover in the uncanny valley of utopia and dystopia, may be experienced in the work, but become heightened when considered in the context of Plato’s allegory of the cave – a framework that Darragh and Kerr deploy to compelling effect.

Is the gallery space the allusive cave, or is the cave located in the immersive projections? Is the visitor catapulted into a cave beyond the work through extremely persuasive algorithms? In some ways these questions manifest Plato’s cave, because they flare around the subject of human perception. If Plato posits the supremacy of philosophical reasoning (the sun outside the cave, the development of the intellect) over sensory knowledge or what is visible (shadows and reflections), it is also tempting to speculate whether In Kahoots merges two knowledge systems: the visible and the intelligible. But this is a distant proposition, and for the time being the original dialectic of the cave is an important heuristic for examining the work.

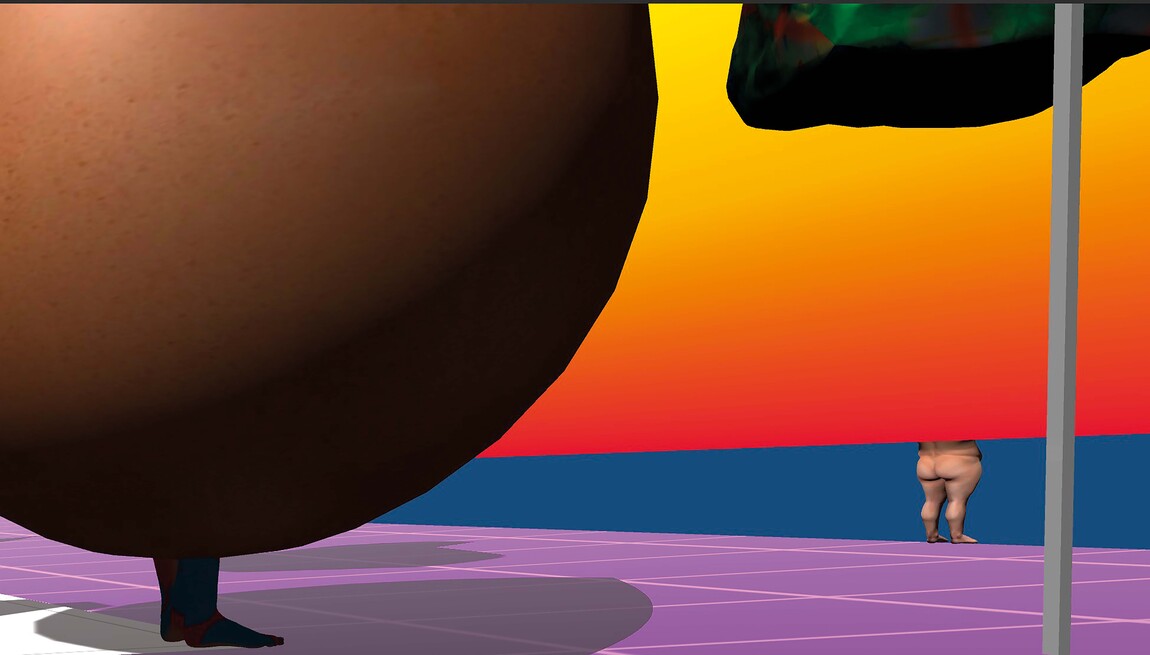

Judy Darragh and Sean Kerr In Kahoots (detail) 2019. Multimedia installation, sound, projected image, Realtime 3D, LED, mirror wall. Courtesy of the artists and Two Rooms, Auckland. With thanks to The University of Auckland Te Whare Wānanga o Tāmaki Makaurau

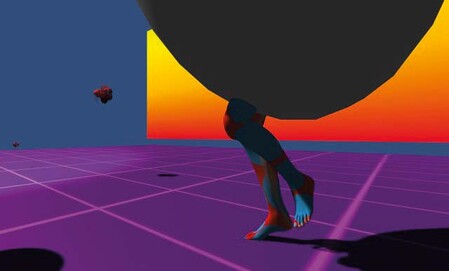

Judy Darragh and Sean Kerr In Kahoots (detail) 2019. Multimedia installation, sound, projected image, Realtime 3D, LED, mirror wall. Courtesy of the artists and Two Rooms, Auckland. With thanks to The University of Auckland Te Whare Wānanga o Tāmaki Makaurau

In Plato’s allegory, this dialectic of sensory knowledge and philosophical reasoning is embodied by shackled cave dwellers who have never been beyond the cave and see only the shadows thrown onto the cave wall (sensory knowledge), and by the artists who walk past a large fire that illuminates the objects they hold above their heads. Those who have escaped the cave and can reflect on what they see and sense around them are considered the Philosopher Kings (reasoning, intellect). As an immersive installation, In Kahoots conjures the reflective properties of Plato’s fire through simulated flames on expansive mirror walls, which makes a case for the gallery space as cave. To complicate this reading however, the 3D projection incorporates a to-scale model of the very gallery space in which it is installed. These various aspects can be regarded as the infrastructural (cave), elemental (fire), and conceptual (perception) apparatuses of Plato’s cave, but things start to get even more interesting when visitors engage with the projections by walking through a beam of light. Is this diffused sunlight that has managed to reach inside the cave? Or does it represent the ascent to sunlight beyond the cave? In either scenario it suggests transformation. But this affirmative potential could be thwarted depending on how the visitor-as-shadow is interpreted. That is, when the visitor crosses the beam of light and activates the sensor, they enter the cave/projection as a shadow. It is as a shadow that the visitor steps into the purple-gridded world, engages with characters, encounters orbs, stelae, monoliths and other lexi-canonical objects from Darragh and Kerr’s back catalogue.

In Plato’s cave, a shadow is what is cast on the cave wall by the artists holding objects in front of the fire. The shadows are simulacra and not the true objects; they represent what is seen or sensed, not what is intellectually known. So what does it mean to be incorporated into this work as a shadow? Perhaps it is an accurate engagement: we enter the work as partially embodied ciphers however flesh-bound our real bodies are. Or perhaps our shadow self is a commentary on the conflicted state of living in the algorithmically generated world of surveillance capitalism and extractivism. One in which we are mined as an extractable resource for our plenitude of data. In any regard, the attempt to recognise shadows by the prisoners in Plato’s allegory was called The Game, and In Kahoots was made in a gaming engine called Unity 3D, so this isn’t a hunt for certainty, but a reflection of the indeterminacy of this work – and indeed of the wider globally networked contexts in which we live.

Shadows and algorithms are relationally engaged with indeterminacy in ways that help us consider life in this time of accelerated alienation, polarisation and protest. The indeterminacy of shadows is immediately perceptible, that of algorithms less so. In most cases the indeterminacy of algorithms describes a state of becoming, processual and relational, rather than its initial construction. That is, algorithms – as precise coded instructions – are primarily oriented towards predetermined goals. The algorithms of search engines like Google, and social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram amongst others, are designed to keep the user engaged. The more time a user spends on these sites, the more invitations they make, the more ads they view, the more money Big Tech makes. Each user on sites like these is subject to data mining by AI algorithms that build profiles to predict behaviour and subsequently feed content to keep us scrolling, clicking, and watching for longer. Such persuasive technologies are designed to make money for Big Tech companies through what is called the attention extraction model.3 In many instances the precision and predictability of these extractive algorithms succeed in garnering user attention, however the direction of that attention can result in apposite real world outcomes: affirmative mobilisation that grows from #hashtag activism4 to IRL (in real life) protests such as Me Too, Protect Ihumātao and Black Lives Matter; or fake news, amplification of white supremacy and political destabilisation that results in IRL violence. This binary configuration could itself be considered a form of polarisation, especially by those in the second clause, but it is not taking place on a platform designed to monetise psychology. Nor, as it will be evident, is Darragh and Kerr’s collaborative work. The algorithms in this work combine precision with indeterminacy: they cultivate uncertainty at the level of code. Here AI algorithms are programmed to direct character movement, edit the actual scenes in the projection, develop songs and generate auto-spoken text. In many respects this is a runaway world of artificial intelligence that eerily parallels the monetised algorithms of Big Tech with their IRL ramifications. In Kahoots reflects our indeterminate reality back to us. Aside from the intended goal of extracting users’ attention, the effects of monetised algorithms beyond this pecuniary orientation cannot be predicted. As ex-Instagram developer Bailey Richardson observes, “algorithms have a mind of their own.”5 This mind, which may have originated in human brain cells, no longer resides there, and is capable of computations (and at speeds) that exceed human capacities. While they continue to proliferate revenue for shareholders, the IRL damage is externalised, or opposition to systemic racism and misogyny are mobilised. Indeterminacy. In the world of quantum mechanics, the projected reality of the shadows on the cave walls are considered more complex than the fire-lit objects.6 Indeterminacy.

Judy Darragh and Sean Kerr In Kahoots (detail) 2019. Multimedia installation, sound, projected image, Realtime 3D, LED, mirror wall. Courtesy of the artists and Two Rooms, Auckland. With thanks to The University of Auckland Te Whare Wānanga o Tāmaki Makaurau

It may be that the visitor-as-shadow who enters In Kahoots is a being variously constituted as simulacra, sensory-oriented, cipher and data mined, and complex, open to jouissance, resistant to polarisation and willing to support those structured into marginalisation. If this is beginning to sound too utopian, In Kahoots asks visitors to at least consider who we are in cahoots with. Even as we are in cahoots with Darragh and Kerr, we are also in cahoots with artificial intelligence and algorithm-generated technology that is always already here IRL. Yet the URL (online) and IRL outcomes of AI with which we are imbricated are also beyond our ken. In Kahoots combines humour, uncertainty and protest that speaks to wider algorithmically driven technologies and uncertain outcomes. These technologies in turn nest and breach interconnected biogeochemical systems that ultimately sustain life on earth. The unpredictability of AI algorithms driven by monetisation can be compared to the commodification of organic life forms such as minerals and forests. Both depend on extractivism in which all beings are “violently turned into ‘thing’ operating as a standing reserve for the accumulation of profit and power in the hands of a few.”7 Who are we in cahoots with? With whom do we kneel and protest? Can we combine sensory and reflective knowledge and resist atomisation?