B.

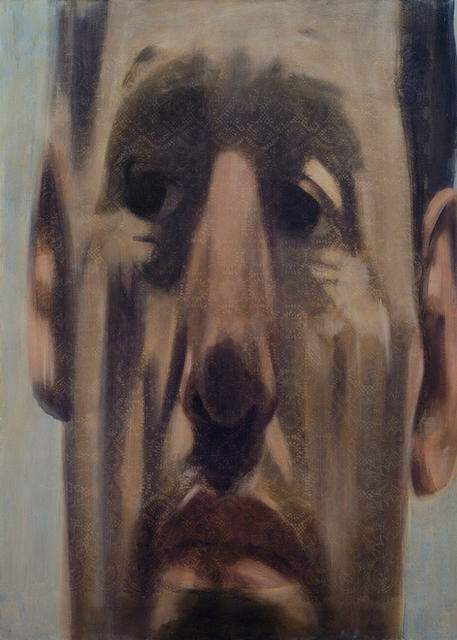

Untitled by Richard McWhannell

Collection

This article first appeared as 'Looking in' in The Press on 17 May 2013

Richard McWhannell Untitled 1998-9 Oil on linen. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery, purchased 2003. Reproduced with permission.

I've always found the act of self-portraiture intriguing. Does back-stage access to an artist's psyche present us with a more insightful image than a likeness depicted solely from the exterior? How much of what we see is real; how much is invention, projection, even self-deception? This large untitled painting by Richard McWhannell seems at first to offer us stripped-back, unflinchingly honest psychological scrutiny. It's an uncomfortably extreme close-up, tightly focused on the eyes and mouth, those traditionally dependable indicators of mood and character. On closer inspection, however, the oversized face proves strangely elusive; the closer we get, the less it seems to reveal. Where we might have hoped to decipher expression or meaning, McWhannell deflects us, deliberately keeping the action on the surface– soft calligraphic strokes that define the contours of the face, pools of shadow that threaten to dissolve them. The prominent eyes, those supposed windows to the soul, slide away, avoiding our gaze and turning inward to some unreachable place.

Born in Akaroa, McWhannell studied at the University of Canterbury in the early 1970s, where he was taught by Rudolf Gopas and influenced by friendships with Toss Woollaston and Tony Fomison. Now living in Auckland, he is a prolific and persistent chronicler of his own image. Over the past three decades, his many self-portraits have depicted a remarkable array of avatars, from pensive to puckish, arrogant to grotesque. He has painted himself as his father, as his son and as a host of figures from art history. In the mid 1990s, McWhannell began a series of large-scale works, in which a recognisable image is distorted and disrupted through a range of interventions – including, as seen in this work, subtle shifts in perspective, dramatic crops and the corruption of his otherwise acute observations with subtle patterns made by painting through a stencil made from a plastic tablecloth. These actions further undermine the authenticity of this apparently simple, but entirely ambivalent, portrait, highlighting the numerous artistic choices involved in its construction.