B.

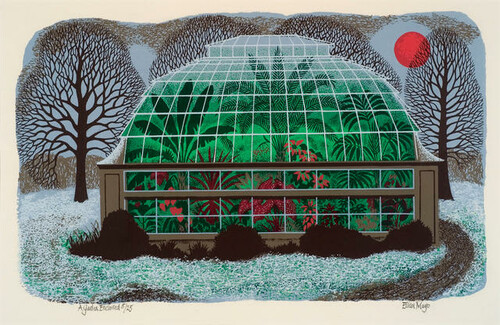

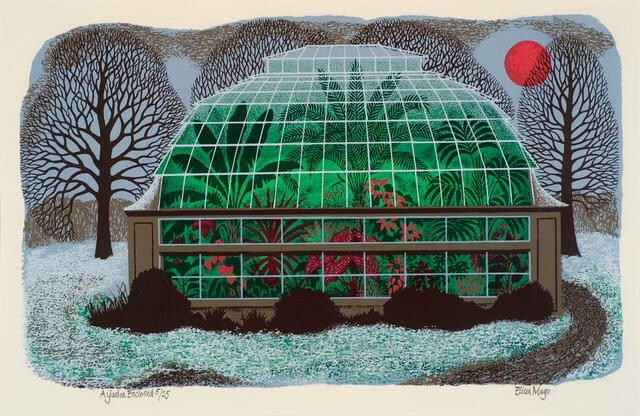

A garden enclosed

Behind the scenes

Last weekend I visited Cuningham House, the grand exhibition glasshouse in the Christchurch Botanic Gardens, which has been newly reopened.

After the earthquakes, though little-damaged, Cuningham House was closed for safety reasons: it was thought for some time that its strength was only at a tiny fraction of the building code. Engineering investigations later established that the concrete columns were full of steel, and after remedial work the building was opened again to the public. On the day I visited, there were dozens of people inside.

Cuningham House was built in 1923. It was designed by leading local architectural firm Collins and Harman, who were the architects for many of Christchurch's most significant heritage buldings, including the now-demolished Christchurch Press building in Cathedral Square, the Sign of the Takahe, and the Curator's House in the Botanic Gardens. Cuningham House was built in the style of the English orangerie or exhibition glasshouse: its design was modelled on the Reid Winter Gardens at Springburn Park in Glasgow.

I've always loved Cuningham House: the heat and humidity that envelopes you as soon as you enter the door, the wide wet staircases with their shallow steps, the scent of perfume and wet earth, the impossibly gaudy tropical flowers, the bananas growing in the middle of a Christchurch winter, the elegant form of the glass and steel roof, the sheer fecundity of the place. It's a lush secret world in which the plants appear to be visibly growing around you. Every time I walk around Cuningham House I'm reminded of Max Frisch's line from the novel Homo Faber (1957)—his hero is in the Guatamalan jungle: 'Wherever he spat, it germinated!'

Over the three or so years that the building was shut up, an automatic watering system kept the large plants alive: many of the potted plants were removed to potting sheds elsewhere. And gradually the plants left behind grew wild. The neo-classical balconies were festooned with creepers which forced their way up to the roof and out of the skylights. On the second storey of the garden, seedlings came up which had hybridised themselves from the tropical pot plants. The life of the place continued in its own way without gardeners to tend it and hold it in check.

Neil Macbeth, Botanic Gardens photographer, via Christchurch City Council, 2013.

Neil Macbeth, Botanic Gardens photographer, via Christchurch City Council, 2013.

During this period of closure, when I thought that Cuningham House might fall victim to the bulldozers which have come in the wake of the earthquakes, I reflected on its place in the identity of the city: it's one of those wonderfully eccentric buildings that represents something particular about local culture. It's something to do, I think, with the tension between the formality of its architecture and the unruliness of its plant collections. A balance between order and disorder held in perpetual tension. Along with Andrew Paterson's splendid Visitors' Centre, which opened earlier this year and stands opposite it in conversation, Cuningham House is the most significant garden building in a city of gardens.

Cuningham House is the subject of a work from Christchurch Art Gallery's collection by the eminent print-maker Eileen Mayo. Mayo was a British artist who settled in Christchurch in 1965 and lived here until her death in 1994, teaching for many years at the University of Canterbury's School of Fine Arts. Mayo's A garden enclosed (1980) is a screenprint which depicts the lush exuberance of the tropical garden contained within the glasshouse, set within a snowy winter landscape of barren trees. The title of Mayo's work is drawn from the biblical Song of Solomon: 'A garden enclosed is my sister, my spouse; a spring shut up, a fountain sealed.' Beauty, constraint, a wilderness held at bay: Cuningham House and its exotic plant collections are elegantly recorded in Mayo's image and her allusive title.