B.

It’s the little things

Behind the scenes

I've never forgotten the story an Australian friend once told me about James Mollison, the former director of the National Gallery of Australia and National Gallery of Victoria.

Reportedly, the formidable director could often be seen walking the galleries, where his attention to detail extended to running a finger along shelves and plinths to check for accumulating dust.

I suppose someone today might object that Gallery directors should be busying themselves with bigger issues. But the point of the anecdote is that dust on a shelf is a big issue. It's the little things as much as the big ones that decisively influence our opinions about a public gallery or museum.

And sometimes it seems that, the bigger the gallery or museum, the more likely it is to overlook the small stuff.

The Louvre, for instance, is one of those museums that recalibrates your sense of what bigness means. On my first ever visit there this August, I kept scrambling for analogies for the museum's stupefying scale, only to give in finally to the truth that there are none, because the Louvre is bigness itself. Uber, mega, beyond grande, it's the measure other museums must submit to.

So it was mildly shocking – and oddly reassuring – to see how patchy, sometimes literally, the rooms of the Louvre can be. Clearly, no Mollison-like perfectionist had strolled recently through the rooms devoted to eighteenth-century French painting, where the wall around a perfect Chardin was crying out for some putty and touch-up paint.

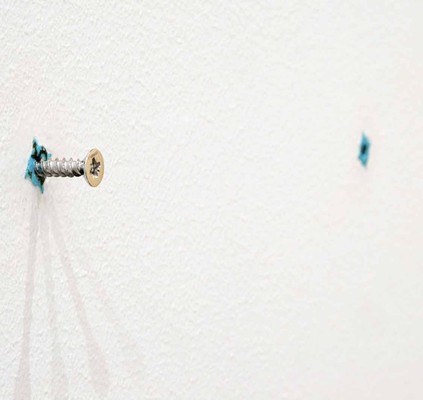

We have a few screw-holes and hanging devices of our own that we plan to leave exposed when Christchurch Art Gallery gets its walls back and we rehang the collection, but these ones, we promise, are special.

Susan Collis As good as it gets 2008-10. 18-carat white gold (hallmarked), white sapphire, turquoise. Purchased for the Christchurch Art Gallery collection in 2011

Custom-made from white gold and turquoise by British sculptor Susan Collis, they're exquisite bits of handwork disguised as dully functional, mass-produced objects. Just the thing to snag the attention of passing viewers – and perhaps the occasional gallery director, too.