B.

Ruinlust

Behind the scenes

Close readers of this blog might have noticed that many of us – curators, teachers, public programmes folk, visitor hosts – are not in our usual offices but instead rubbing shoulders in the Gallery's library. And naturally, we're glad to see visitors. But a week or so ago the human residents of the library were thoroughly upstaged by – what do you know – a book. Or rather 'the book', because that's what visitors called it when they came in for a viewing. Its reputation preceded it.

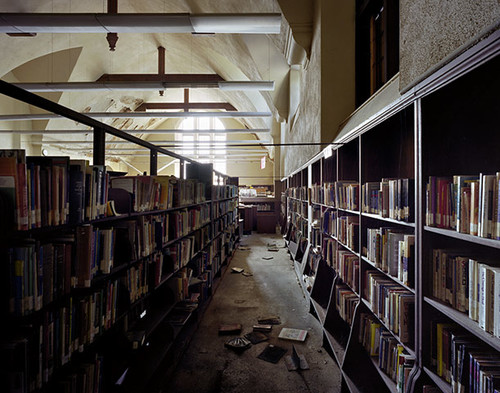

East Side Public Library. Photo: Yves Marchand and Romain Meffre. Image: http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/gallery/2011/jan/02/photography-detroit#/?picture=370173040&index=3

The book is The Ruins of Detroit, by French photographers Yves Marchand and Romain Meffre, and it is a gasp-inducer. Not the kind of publication you want to try balancing on your knees while eating lunch, it has the weight and proportions of a small tombstone, and what's inside doesn't exactly quell the funereal feel. Detroit, the one-time hub of American automotive-industrial might, sank through the 1980s into a state of recession and urban blight that still looks (despite some twitchings of gentrification) irreversible. Marchand and Meffre have crawled all over the city's vacant centre and come back with the proverbial goods: hundreds of photographs so bleak and so beautiful that it's hard to know how to respond.

The Ruins of Detroit, published by Steidl. Introductions by Robert Polidori and Thomas Sugrue. 230 pages, 186 colour plates, 38 cm x 29 cm

Grand tourists used to head to continental Europe in the 1700s and 1800s to bask in the magnificence of its ruins. There is even a word – ruenlust – for this appetite for loss and decay. Contemplating some toppled column or time-raddled amphitheatre, a grand tourist could at once recall the glory of past empires and meditate on their decline. Marchand and Meffre deliver that feeling, but in an uncomfortably concentrated dose, because in their book we seem to see the ruins not of the past but of the present. A world not so different from our own, but viewed as if from the vantage-point of the future. Here in Christchurch we're used to the seeing ruins created in a matter of seconds by Mother Nature, but Marchand and Meffre provide proof that Father Recession can do the job just as well – albeit more slowly.

The proof includes battalions of dead-eyed apartment blocks, colossal 1920s ballrooms whose ceilings seem to be weeping asbestos, mansions that have slumped like wedding cakes left in the rain, and a million piercing tiny details: look at the pinchpots grouped like frightened civilians on the table of an abandoned craft workshop; or at the school clock whose face has melted, as if channelling Salvador Dali. Even the 'Missing' sign on a police station wall appears to have been prepared in anticipation of this slow catastrophe – it might be referring to the inner city's entire population.

The ruined Spanish-Gothic interior of the United Artists Theater in Detroit. The cinema was built in 1928 by C. Howard Crane, and finally closed in 1974. Photo: Yves Marchand and Romain Meffre. Image: http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/gallery/2011/jan/02/photography-detroit

Though some of the pictures could well be reckoned too beautiful for their own good, Marchand and Meffre use words judiciously to keep the rapture in check. Just when you're tempted to start swooning over the crystalline sharpness of the prints or their smouldering, high-Renaissance colours, the caption line at the bottom of the page snags you with some socio-political fact and pulls the whole experience back into the realm of the real. Reminds you, in short, that people lived and worked here. Not that anyone in Christchurch at the moment is likely to need that kind of reminder.

The most shocking photographs in the book are not of mouldering movie palaces or ransacked cop-shops but – fittingly enough, given where many of us are working within the Gallery – of libraries. One of the least dramatic pictures in the book is of Mark Twain Public Library. All the books are still on the shelves. It looks like a pleasant enough place to be. But no one has browsed here for decades. Who locks and leaves a library, you wonder? A bankrupt city, is who. It's a chilling sight, like a lost memory of humanity's better impulses. And the photograph Marchand and Meffre make of it has the reserve and ringing clarity of an indictment.

Still, I see an upside. These days it's impossible to open one's ears without hearing someone go on (and on and on, usually) about the rise of e-books and the death of physical ones. Despite its tombstone proportions, and despite that melancholy photo of the library, The Ruins of Detroit makes a truly formidable case for the life and necessity of the book.