Hidden in Plain Sight

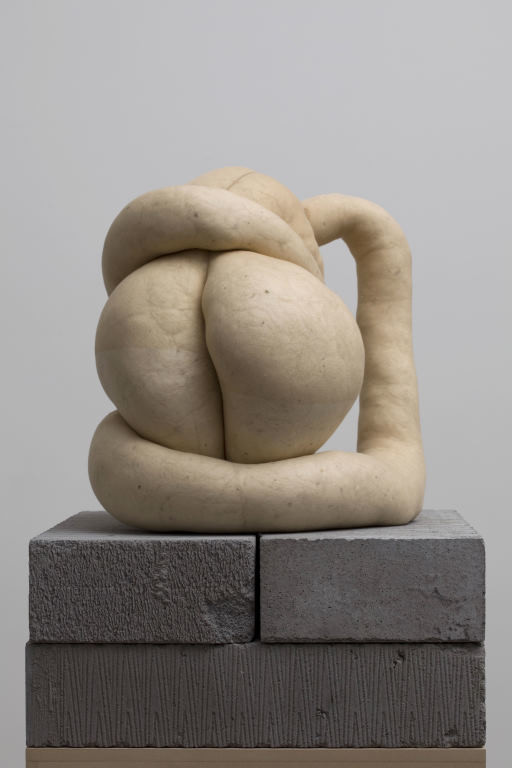

Joe Sheehan Mother 2008. Greywacke stone. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2008. Reproduced courtesy of the artist and Tim Melville Gallery

In 1997, I went to see an exhibition called White Out, curated by William McAloon for Auckland Art Gallery’s contemporary space. The show’s subtitle unambiguously promised ‘Recent Works by Seven Artists’, but as I completed my circuit I realised I’d come up one maker short.

I went through again, looking more closely. Still no luck. By the time I found Now and Then, Simon Morris’s shimmering sequence of crosses painted in clear varnish across a white wall, I was applying a heightened level of concentration that felt quite different to my usual gallery-going demeanour. Having to hunt out the work had somehow primed me for the experience of seeing it, and rather than generating the frustration or annoyance I might have anticipated, my brain was crackling with thoughts about whiteness and lightness, surface and reflection; how the quality of light can alter perspective; how things can be both present and absent, subtle and intense. Morris’s sleight-of-hand had operated as a delaying tactic that conditioned me for a more meaningful viewing encounter, and I was intrigued to find that this intensified consciousness carried over, for a while at least, into my experience of the other works I came across as I left the White Out space.

Glen Hayward Shrink Wrap 2004. Wood and acrylic paint. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, the Jim Barr and Mary Barr Gift 2011

Illusion and misdirection have long been part of art; ancient Roman murals in Pompeii fooled the eye with false windows and lifelike insects, and the Greek painter Zeuxis reportedly painted grapes so realistic the birds flew down to peck them. Since the arrival of Marcel Duchamp’s revolutionary readymades in the early twentieth century, everyday objects – modified, juxtaposed, or merely transformed by their relocation into galleries – have been added to the contemporary artist’s arsenal. As a result, many visitors arrive with increasingly suspicious eyes, a wariness perhaps vindicated by recent events at the Dallas Art Museum. In April 2015, two high-school students created an impromptu, tongue-in-cheek art installation, arranging a watch and pair of sunglasses on the floor of an abstract art exhibition. They photographed the reactions of visitors and later posted them on the social networking/news site Reddit.1 As one prankster, Jack Durham, told the Dallas Morning News, ‘A lot of people were like, “There’s no way this is real.” But some people were thinking “Wow, I wonder what this means?”’2 Predictably, reactions to the stunt were mixed. Many commentators saw it as a timely puncturing of the pretentions of modern art – a contemporary version of the ‘Emperor’s New Clothes’ – and it was gleefully reported from that angle across the web. Others, however, interpreted it as a natural extension of Duchampian process: Reddit user WGHHUA wrote ‘You think you made fun of art, but you created art. Joke’s on you.’3 The museum’s director, Maxwell Anderson, took a benevolent view, calling it ‘a modest, cheeky guerrilla action in keeping with a venerable tradition’.4

The tensions and uncertainties surrounding an audience’s expectations about what art can be, and how they should respond to it, provide fertile ground for contemporary artists who choose to send their works deep undercover. In Christchurch Art Gallery’s collection, works by Joe Sheehan, Glen Hayward and Susan Collis reveal how subterfuges, doubletakes and slow reveals can act as catalysts for more lingering and attentive art experiences.

... the artist didn’t go out into the world to gather everyday objects; he went back to his studio and made them by hand.

Glen Hayward Yertle 2011. Wood (kauri, pine, pūriri, rimu, tōtara), acrylic paint, wire. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2011

Mention ‘carved stone’ and people’s thoughts might turn to marble, shaped into cool classical curves, or perhaps a pounamu heitiki, glinting with the green light of deep water. Few would think of greywacke, the common argillaceous rock found throughout the eastern South Island, which originally accumulated as sediment at the edges of the Gondwana super-continent. And how many would connect that stone with a plastic milk bottle, crushed and compacted almost beyond recognition? New Zealand sculptor Joe Sheehan brings these unlikely companions together, under an even less expected title: Mother. If the distorted form of the bottle is unmistakably contemporary, the stone carries us back many millions of years. However, both were formed as the result of irresistible external forces. Holding this in your mind as your eye traces the undulating and deceptively fluid lines of the stone makes for a captivating encounter. Radiating out with conflicting histories and associations, it’s the kind of juxtaposition that is typical of Sheehan’s practice, which gains much of its impact from the convincing way he replicates the perfection of industrially-produced surfaces. In his hands, solid stone has masqueraded as a wide range of contemporary objects, from light bulbs, sunglasses and ballpoint pens to a pounamu cassette tape.

Material deception is also at the heart of Glen Hayward’s sculptures, four of which currently lurk, like unexploded ordnances, in the Unseen exhibition. The first of these, Shrink Wrap, is a beaten-up recycling bin in the faded blue livery of the Auckland City Council. Tilted over on one side, it’s just begging to be set to rights and tidied away; from the expressions on some visitors’ faces, it’ obvious that’s just what they’d like to do. Motivated by as much irritation as curiosity, they stalk around it – but they’re in for a surprise. The bin that seemed empty is actually full, stuffed not with last week’s newspapers or the weekend’s empties, but wood. Or more accurately, like all of Hayward’s works in Unseen – and like Yertle, his teetering paint-pot tower upstairs – it’s been carved from wood and then painted with Machiavellian attention to detail. Like Sheehan (and unlike Duchamp) the artist didn’t go out into the world to gather everyday objects; he went back to his studio and made them by hand. It’s interesting to witness the recalibration in visitors’ attitudes as they process this difference: suddenly what seemed like a trashy plastic intrusion represents hours of meticulous labour and considerable skill. And by lavishing such time and attention on something that’s all about what’s thrown away, Hayward invests his works and process not only with humour, but with an unexpected gravitas. Unlike Shrink Wrap, the three other Hayward works aren’t noticeably out of place – they’re all objects that might conceivably be found in a gallery space and it’s only when you get closer (or read the wall label) that you realise something’s not quite right. That venerable fire extinguisher, faded and weathered through years of vigilant readiness, was carved from native tŌtara. A grimy light switch nearby has undergone a switch of its own. It’s also made from wood, but its surface was whitened with correction fluid rather than paint and fittingly – given its inability to perform the one task we might expect of it – it carries the moniker of Typo. The watchful visitors who discover these secret identities may pause to query an apparent duplication of surveillance equipment on an adjacent wall. Halfway down, that extra security camera seems curiously outdated, and a check of the wall label offers another clue; in a sly nod to the tight conceptual loop that contains the artist and the viewer, now caught in his hoax camera’s sights, Hayward calls this one Closed Circuit.

Susan Collis As good as it gets 2008–10. 18-carat white gold (hallmarked), white sapphire, turquoise. Collection of Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū, purchased 2011

Many clandestine works draw the viewer’s notice to the context of the gallery space – those deliberately calibrated walls, rooms and openings we often overlook, but which unquestionably influence our viewing experience. For British artist Susan Collis, the pristine sanctity of ‘white cube’ spaces is an invitation for mischief-making: she clutters them up with things we’d expect to be hidden away: dust-cloths, overalls, stepladders, sawhorses. Careful inspection reveals these untidy cast-offs as meticulously realised deceptions, exquisitely rendered in a range of precious materials. That rickety stepladder is speckled not with drips of paint, but with inlaid diamonds, opals and pearls, while the stains on a series of crumpled up dust-cloths are painstakingly rendered in delicate embroidery. When Collis’s As good as it gets was installed for the earthquake-curtailed exhibition De-Building, visitors were confronted with three raw screw holes on an otherwise blank wall. Two were occupied by rawlplugs; the third also held a solitary screw. Many must have wondered if a work had been stolen or left mistakenly in storage, but in the kind of payoff usually reserved for those who do good deeds in fairytales, attentive viewing was rewarded with glittering treasure. The unsightly plastic rawlplugs were in fact delicate turquoise inlays, and the ‘forgotten’ screw had been cast in 18-carat white gold and set with a sparkling white sapphire. The work may have been subtle, but the message was clear: the longer (and harder) you look (and think), the more you’ll see. Modern life places ever-increasing demands on our attention: behind every browser tab, there’s another waiting to be opened; articles splinter into a gorgon’s head of tantalising hyperlinks. Prioritising speed and scope over immersion, we are in danger of processing images as though we were inferior computers, rather than engaging with our human capacity for thought, emotion, memory and analysis. For that, we need moments of stillness; accumulations of time. Elusive works, like those made by Sheehan, Hayward and Collis play a high-stakes game; risking being overlooked altogether, they gamble that those who do spend the time to find them will leave far richer for their efforts.

Felicity Milburn

Curator