The Garden of Cosmic Speculation

The Snail Mound is next to the Snake Mound, neither named except for those who built it in machines and had to know. The landforms sculpt the might with their paths — sharp-edged and with sweet curves so the morning and evening light accentuates the earth’s shape.

Over several years I have worked on a Scottish landscape called, immodestly, the Garden of Cosmic Speculation, speculating with scientists and others on the fundamental laws and forces behind nature and what they might mean to us. Using growing nature to conjecture on what is basic to the universe is an old practice common to gardeners, but it raises some unlikely questions.

Most people understand a big distinction between living nature and the laws of nature – that is, organic growth and electromagnetism – and they do not reflect that in a garden as elsewhere the latter may underpin the former. Furthermore, the gardens of the last hundred years are for pleasure and relaxation, games and flowers, and not a place for public art. A big question follows from this: what, in our fragmenting culture, could communal expression achieve today, especially in an era driven by a runaway art market and fast change (not to mention toxic debt)? What beliefs command assent or, to shift to the public realm; which clients are brave enough to pay for a public park dedicated to a significant idea? My own experience in Italian and German parks is that to get any agreement on content is an uphill struggle, though very much worth trying.

It is much easier to experiment on oneself, and here I have been fortunate. My late wife Maggie and I started work on this garden around her family home in 1988 and slowly, area by area, it has grown into a landscape with about twenty areas dedicated to the fundamental units of the universe: a Black Hole Terrace for dining on in the summer months; a DNA Garden of the six senses; the Quark Walk; the Universe Cascade and so on. Each insight into deep nature, many of which are recent, becomes translated into nature and sculpture. Landform is my generic name for this genre that cuts across art, landscape, architecture and the customary categories, and there must be something like twenty-five of them throughout the garden. Some landforms refer to theories of folding and fractals, others (when they fail) to catastrophe theory. As every gardener knows, the dialogue with nature is always two-way and it pays to exploit the unintended consequences of nature's acts.

DNA Garden

Why dedicate a garden to the laws of nature? Partly because everybody relates consciously or not to the larger picture; we identify with nature and its various moods and states. And partly because in an era of global turmoil, when Tracey Emin and Damien Hirst are the public face of art, these cosmic laws can give us a public iconography that is as eternal as anything there is, and more engaging than an unmade bed. But the emergent iconography of the universe, as seen through the culture of science, has one big public problem: the interpreters tend to follow Emin/Hirst & Co. Hence for the birth of the universe we get the metaphor of a 'Big Bang' — used by ninety-nine per cent of scientists to describe the mother of all things. It wasn't big (the inflation of a quark-sized event), and it wasn't a bang (no one heard it). Rather it was the 'hot stretch' of space that balanced the basic forces (a much more engaging idea). Fred Hoyle coined the adolescent Big Bang metaphor derisively, but it caught on for the same reason that George Bush was able to coin 'Shock and Awe' for his bombing of Iraq. We live in a Pentagon-driven world where scientists in charge of the public understanding of nature regularly tell us that 'selfish genes' are in charge of robot vehicles, and that 'Wimps and Machos' are the ultimate stuff of the universe.

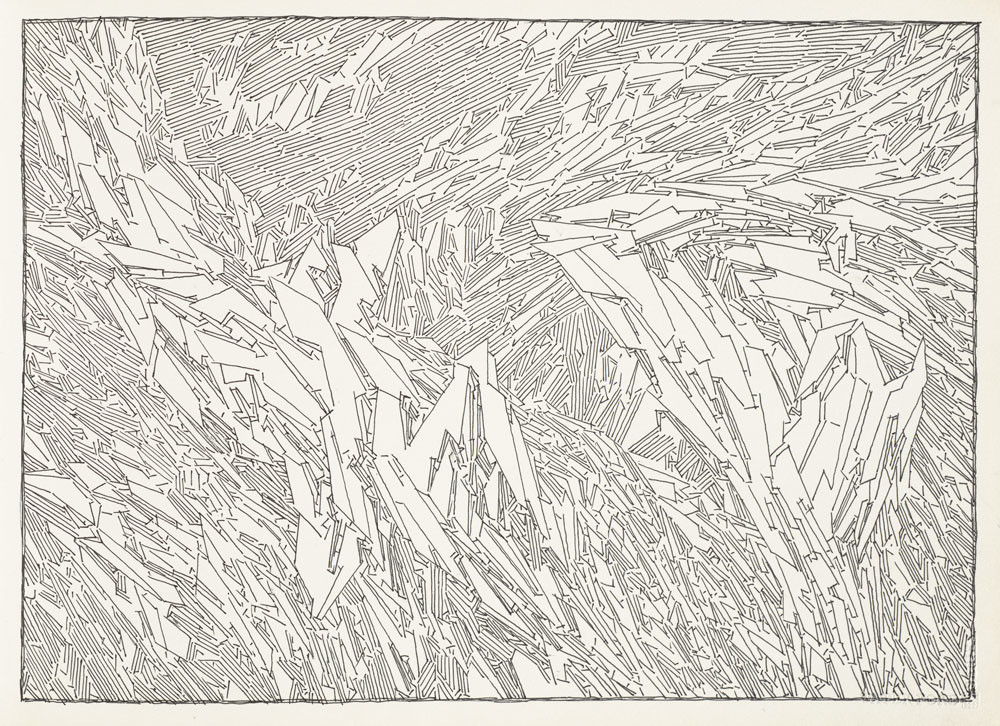

The Universe Cascade

So, in the Garden of Cosmic Speculation I try out questioning metaphors, and this means that all design is really double design: that is, solving formal and functional problems, and coming up with new, appropriate metaphors (both visual and verbal). For instance, the Black Hole Terrace shows the space-time warps of super-gravity, the event horizons and rips in space-time. However, as design was progressing in 1995, and many were discovered and thought to lie at the centre of galaxies, the metaphor was changed to 'Invisibilia', the female generator that helps hold much of the stars, planets and gas in their rotational shape. It is not just destructive, but a creative force. When the Chinese asked me to design a rotating black hole for the Beijing Olympics, they accepted the design with delight but asked for a name change. We came up with several including Wu-Ji, and Wu-Chi, varying from 'nameless chaos' to the 'mother of everything'. Re-naming and re-conceiving go together, and so I have come up with a series of different visual metaphors for the basic things. Fundamental to the whole garden is the 'jumping universe', which is portrayed in the cascade that tells the story of the cosmos over its 13.7 billion years; and a 'landscape of waves', for the undulating and linear language that unifies everything. Everything, physicists show, has its wave-form.

Public art must of course be understandable and moving, but I believe it also should engage with the basic insights on the cosmos. This endeavour is collective, part of what has been called The Universe Project, where no one has the last word. A hopeful sign is that The Royal Society of Chemistry has just re-christened the Large Hadron Collider ‘Halo’ after running a contest to find a more appropriate moniker for the atom-smasher — name changes are a minor but significant place to start in the creation of a more public culture, even while acknowledging that no one controls language. ‘Shock and Awe’ and ‘selfish gene’ were intended to catch on and they did, and as Walt Disney once said, ‘no one ever went broke underestimating the taste of the American public’. But it is also true that there is a large public fed up with this regressive taste, waiting to feed on a culture that is more nourishing, and true, to life.

Charles Jencks is an American architectural theorist, landscape architect and designer. He has written widely on the history and criticism of modernism and postmodernism, particularly in relation to architecture, and is a leading figure in British landscape architecture.