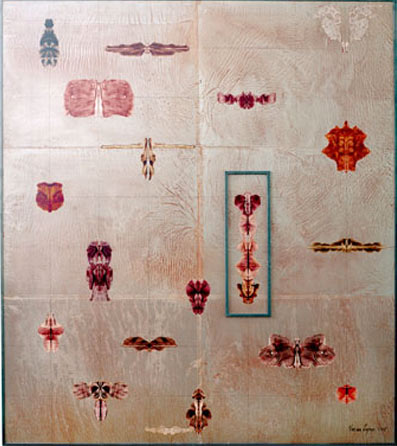

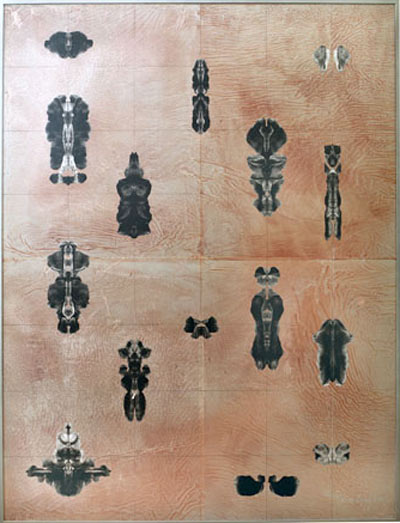

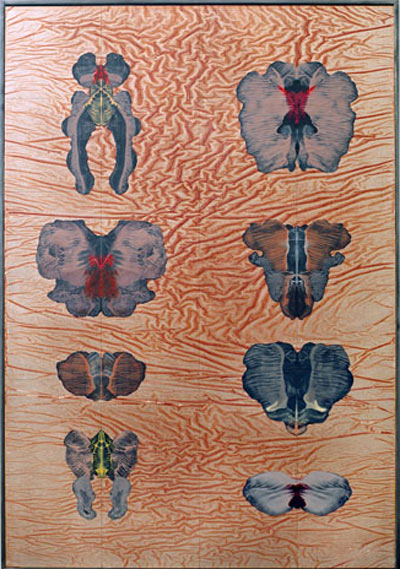

“What I learned at art school? I could list form studies, drawing, colour and say that I learned to see, but the most important thing was, that my conviction that I was an artist was never put in doubt.” Your Mental Set: Mind Fields, Exhibited at the Mark Hutchins Gallery, Wellington, 25th September–13th October 2007 From a body of work begun in 1988 these paintings work with themes of projection, identity, cultural memory and mutability through the free forms of Rorschach ink blots. These works are not about something, they are arrived at from my ground of experience which has long eschewed the notion of a stable, enduring inner self-and identity - the unified individual - in favour of a corporeal, visceral, neural, erotic mind self in the world, where identity emerges, ebbs, flows and mutates from behaviour in the lived space we inhabit. No awful inner self but an epidermal self, where as Sappho said, " a subtle fire has stolen beneath my flesh".

|

I was a student at the School of Fine Arts in 1949, 1950 and 1951, and majored in painting. In 1949 my teachers were, Rata Lovell-Smith for still life, Jack Knight for drawing from the antique and anatomy, and Colin Lovell-Smith for composition. Through 1949 to 1951, Russell Clark taught life painting and life drawing, Bill Sutton, life drawing and landscape painting , and John Oakley, the history of art and the history of painting. Ivy Fife taught portraiture in 1950. My peer group included Campbell Smith, Sue Skerman, Bruce Rennie, Geoff Fuller and Pat Jones. In 1949 I found Christchurch and the art school dull, absorbed in middle-class notions of class and breeding, and nineteenth century in outlook. Christchurch was foreign in its Englishness. A Wellingtonian, reared in a culturally rich, “modern” family, whose roots were established in Invercargill and Dunedin in the 1870s, I was at odds when I first arrived in Christchurch, as too was the only Maori student to appear in my classes during those years, and a North islander who kept to himself as he laboured fervently under the life room’s greying skylights, piling hot colour onto rough green grounds. Not for him the smooth gesso covered canvases we were taught to prepare. Neither student stayed long and the latter had some success in London. As it transpired, in 1949, the art school was at the end of an era. Before the war it was perceived by some as a finishing school for the dilettante sons and daughters of the wealthy middle class and that view persisted into the time I was a student. I remember being deeply surprised by a comment to that effect from a local engineering student. If there was any truth to that perception of art students, it changed after the war, when the government established ‘free’ tertiary education, “rehab” loans for ex-service personnel and bursaries for the (ten?) top-ranking students who passed the Diploma of Fine Arts Preliminary exam. Consequently the student body became more socially diverse. Another change, although frowned upon, made it possible to obtain a Diploma of Fine Arts in only three years. For many, the diploma was a qualification for teaching in secondary schools, as to be an artist usually required becoming a teacher. From 1951 graduands could enrol in the newly established Division C at Auckland Teachers Training College for a Diploma in Teaching. At this time, art education and child art in New Zealand was promoted by Dr [Clarence] Beeby and other enlightened educators. It was a brilliant period for art education and my introduction to child art was riveting. I've taken time here to give you a sketchy outline of the socio-political changes in New Zealand, which changed attitudes in the student body, which in turn changed the social scene in the school. In my peer group there was generally a faster pace and more serious approach to study than had existed, which still left room for escapades, dancing and parties. Traditionally we took painting trips to the mountains at relax – places like Cass, Arthur's Pass and Homebush, where we listened to 78 records, talked, walked, wrote poetry, painted, collected coal from the rail track for the fire and didn't really get drunk! The cultural toys were few so we made our own fun. So when I arrived in 1949 the old faculty was devolving and a new one being put in place. Rata Lovell-Smith and Francis Shurrock were taking their last classes, Russell Clark, with a background as a war artist and illustrator, known for his drawings of Maori, was the main teacher and Bill Sutton's return from England was anticipated. There was a sense that fusty nineteenth-century art ideals were on the way out. Regarding influences and international developments in contemporary art - the major study at art school was not Contemporary Art but The History of Art and The History of Painting and that meant mainly European. There were many influences such as Masaccio and Piero della Francesca, as well as African and Asian arts. In relation to the contemporary scene, although I did meet and see the work of Toss Woollaston, Doris Lusk, Rita Angus, Colin McCahon and others in The Group shows in Christchurch over those years, their work did not impact on me until later. When you realize that in Britain, the Institute of Contemporary Arts was only founded in London in 1947 and that Henry Moore was the principle exhibitor in the 1948 Venice Biennale and awarded the international prize for sculpture, you see how privileged we were to have a hot line to Henry Moore through Russell Clark’s (brother?), who was an assistant to Henry Moore. Russell shared with some of us his brother’s letters and images of Moore’s shelter drawings, the aerial lanscapes of Paul Nash, and the sketches of furnaces and mines made by Graham Sutherland. These works were made during the war as official records. They were not “war art” but personal works and were said to be a new form of allegorical painting, having made symbols out of events. I was not sympathetic to Surrealism which was being discussed at the time but was influenced by the human psychological content in these “allegorical”works. International art exchanges were in their infancy so there were few Contemporary art journals. We looked to the sparse art section of the city library for images as there was no art school library to speak of. Picasso was an obvious influence on students but was more or less a rude word at art school. I remember the huge impact on first seeing a print of Guernica, after I left art school perhaps. It was as though Guernica was what I had been waiting to see. Later at MOMA, in New York City, seeing it in reality for the first time ,was one of the great overwhelming experiences which I put alongside Grunewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece. Reflecting on the art school I hypothesized that a schism existed within the art school which reflected the Christchurch zeitgeist epitomized by the pioneering Southener in an English over cloak and that perhaps the struggle to disrobe, is what has produced the edgy intellect behind much of the work which later emerged from Christchurch. What I learned at art school? I could list form studies, drawing, colour and say that I learned to see, but the most important thing was, that my conviction that I was an artist was never put in doubt. I imagined I would be an artist and travel. I did both, married, became a lecturer and my most recent exhibition was at Mark Hutchins Gallery, Wellington, 25 September – 13 October 2007. If I hadn't gone to art school? Who knows?. I would also have met different people. Its effect on my subsequent career? It prepared me with a structure to pursue my practice – from daily work in the studio to exhibiting. By doing that I could begin my discoveries. |

||||||||||||