Petrus's Otira

By Edward Sakowski

Every conservation treatment and every technical study of a particular painting begins with a thorough visual examination of the artwork in ordinary light.

Prior to any conservation treatment, a work of art is examined to determine its structure and condition. It is not unusual for old paintings to have characteristic damage that provides clues to an understanding of their history.

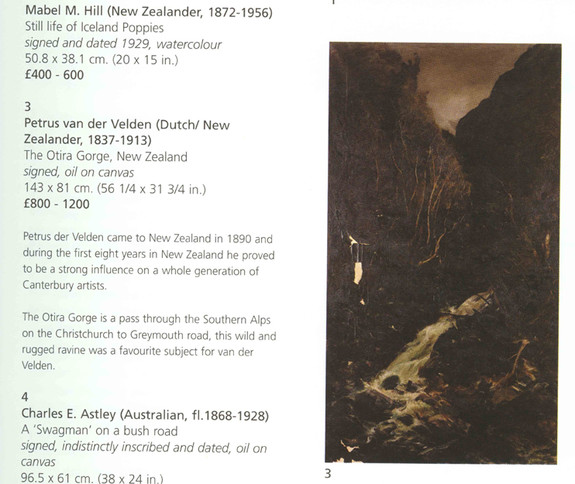

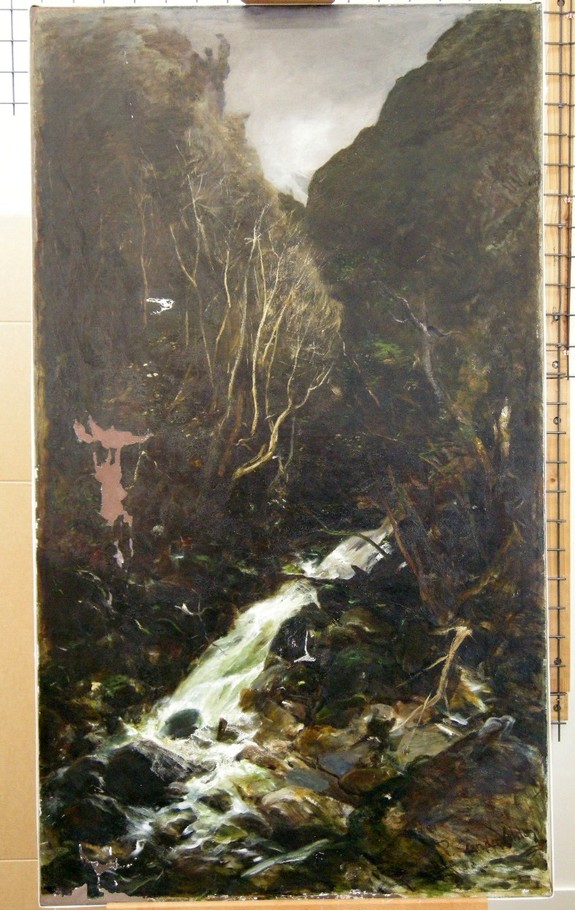

Jackson’s Otira had numerous losses. Some of them were visible on the catalogue photograph and at that time the cause of this damage was unknown to us.

Before arriving in New Zealand, the back of this painting had been exposed for a long period to water penetration. This caused a very large area of damp canvas on the left hand side and at the bottom of the image. The dampness of the canvas and then its rapid drying caused areas of ground and paint separation from the support. It also caused very substantial structural losses while in transit from Britain when the painting was subjected to many hours of constant vibration.

Also when the damp canvas dried and shrunk the paint and ground film made numbers of vertical creases and ridges standing up

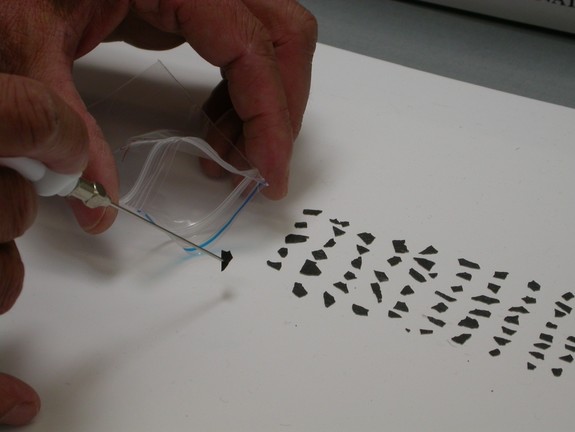

Most of the loose fragments were collected, numbered and placed in plastic bags. Unfortunately at that stage it was not possible to put them all together. This process would require computer help to place each piece in the right place. This big puzzle – there are over 400 pieces of broken paint film and some of them are very very small - is still waiting for a computer wizard!

Some deterioration had occurred a long time before the painting was placed in the auction room. This damage was a consequence of the artist's inadequate technique. Most of the drying cracks had been caused by the use of bitumen and only allowing a very short time between paint coats.

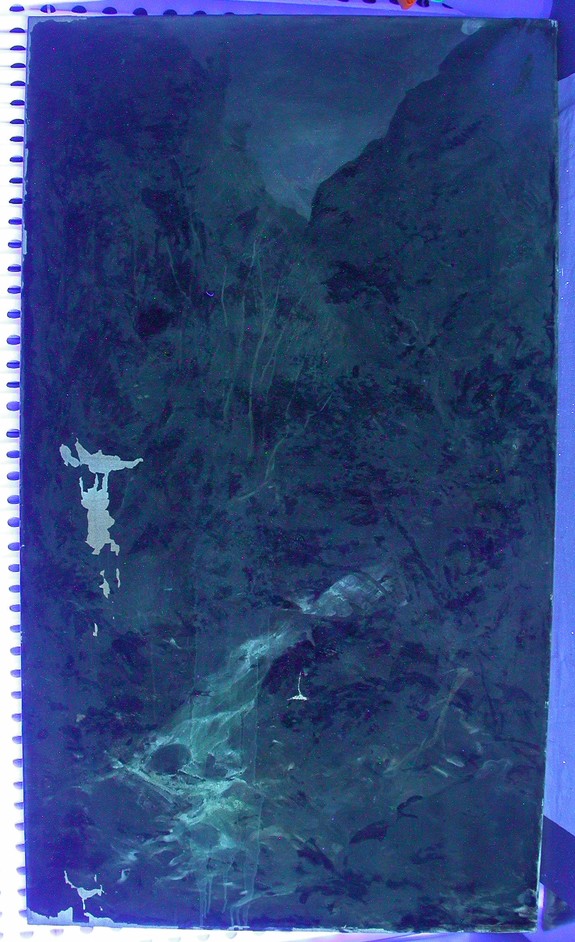

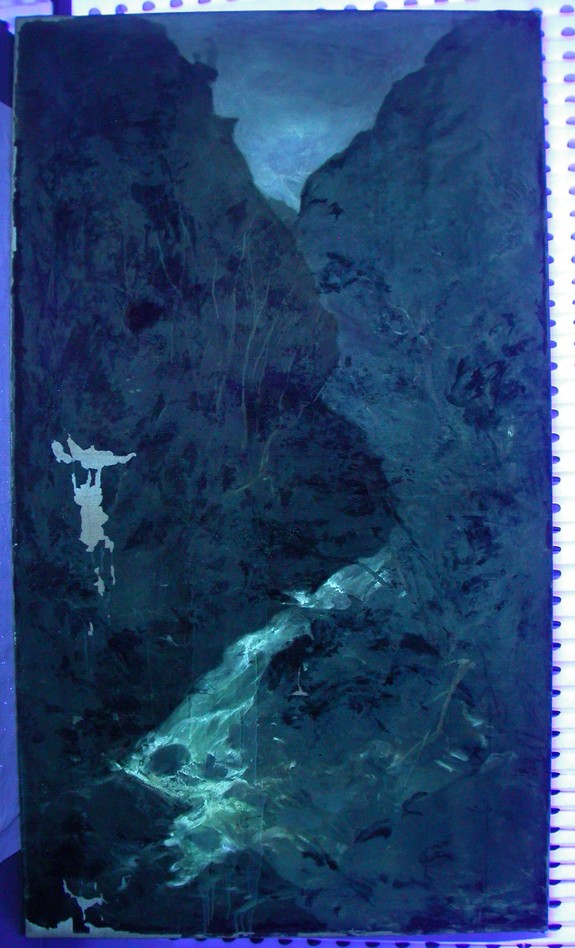

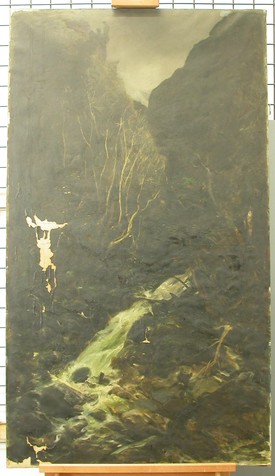

The examination of paintings with ultraviolet is also part of the pre-treatment documentation process. Examination of Jackson’s Otira under ultraviolet revealed little of interest other than a general fluorescence of an aged natural resin varnish.

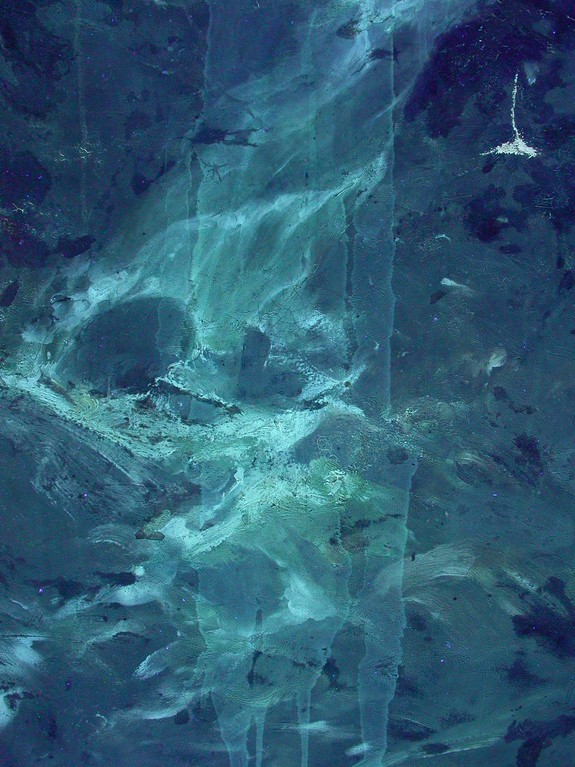

Only the centre of the painting showed some kind of accident during the varnishing process, or an accidental later spill that was not removed or brushed off from the surface. When it was allowed to dry on the top layer, it shows us a spectacular waterfall which is invisible in daylight.

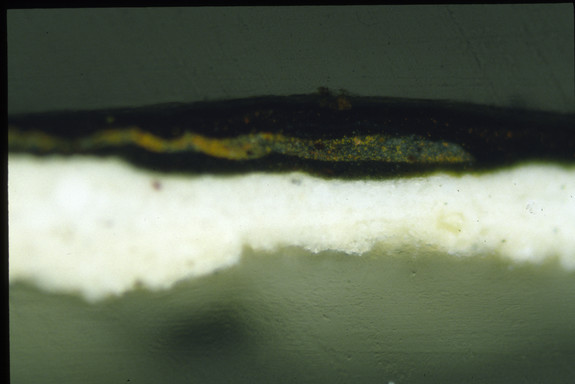

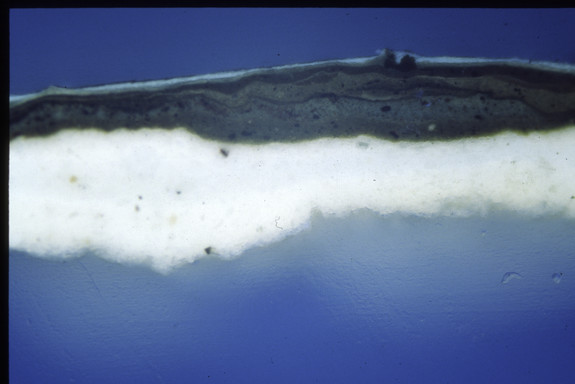

Layers of varnish, paint and ground can be examined, and the fuzzy or sharp interface between layers indicates whether they were applied wet-in-wet or after a period of drying. The size of samples varies from a pin-point to a pin-head. In this case the samples ware bigger as they were taken from paint chips broken away. All these samples were prepared by conservation department at the Auckland Art Gallery.

For a cross-section, the sample must be taken through more than one layer of paint and remain coherent. The sample is placed on a solid block of transparent synthetic resin in a mould and further liquid resin is added to embed the sample. Once set, this is ground down carefully at right angles to the paint surface, until the sample is exposed edge-on. It is then polished, and viewed in reflected light under a microscope.

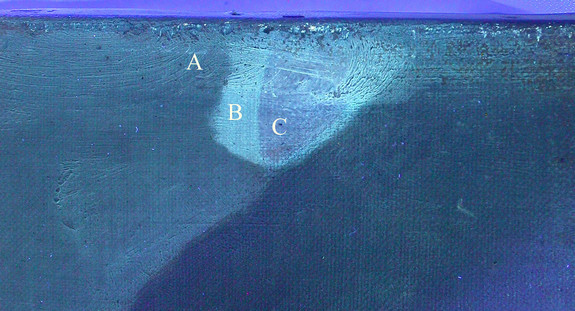

A - The all flaking paint film has been stabilize with conservation glue

B - Canvas has been removed from the stretcher and all taking margins have been flattened

C - Paint film has been protected with conservation glue

D – The old patch from verso and gesso on the original paint film have been removed

E - Solvent tests were undertaken to determine the most suitable mixture to remove surface dirt and dust and the discoloured varnish.

F - Old fills were partially removed and all new areas were filled with synthetic gesso.

A - Dark grey-blue layer on the left – surface dirt and dust

B - Light white-blue layer – old varnish

C - Light violet layer –original paint surface

Old varnish has been removed from the left side of the image and the deep dark blue surface of the original paint film has been exposed.

Surface dirt and dust have been removed from the right side of the image and a light blue film of old varnish has been exposed.

Prior to inpainting, the work was varnished. Varnishing at this stage enables the conservator to accurately match the colour of the new inpainting with the saturated and final colour of the painting. It also provides an isolating layer between the original paint and the paint applied by the conservator.

Originally, Jackson’s Otira would have been coated with a varnish made from a natural resin, such as copal, damar or mastic. Conservators recognise the limitations of natural resin varnishes and often coat paintings undergoing conservation treatments with synthetic resin varnishes. Synthetic resin varnishes have greater light stability but do not saturate paintings in the same way as natural resin varnishes. Paintings that have dark areas, such as the bush or stones in Jacksons Otira painting can appear a little grey if coated with a synthetic resin varnish. In order to avoid this problem, the painting was given a very thin coating of dilute Paraloid B72 in Xylene

Conservators are very particular that their inpainting does not extend over the artist's paint. Inpainting also has to reflect the character and age of the work undergoing treatment. A worn and aged painting should retain an appearance of age and not be 'restored' to appear as if it is in an undamaged state.

The contemporary inpainting medium used by conservators for oil paintings is generally powdered pigments mixed with acrylic resin. This is done to discriminate between the original paint and that applied by a conservator. The compensation of losses can be a most satisfying aspect of a conservation treatment. As the losses are inpainted, the damages become less visually obtrusive and the painting once again appears whole. Of course inpainting can be a most frustrating chore when one cannot seem to get the right colour to match the original. Inpainting the numerous losses on Jackson’s Otira proceeded smoothly.

After inpainting, the work was given a final thin coating of damar varnish. This presents the painting with a unified surface and further saturates the colours.

The completed painting was returned to its new frame and returned to exhibition.