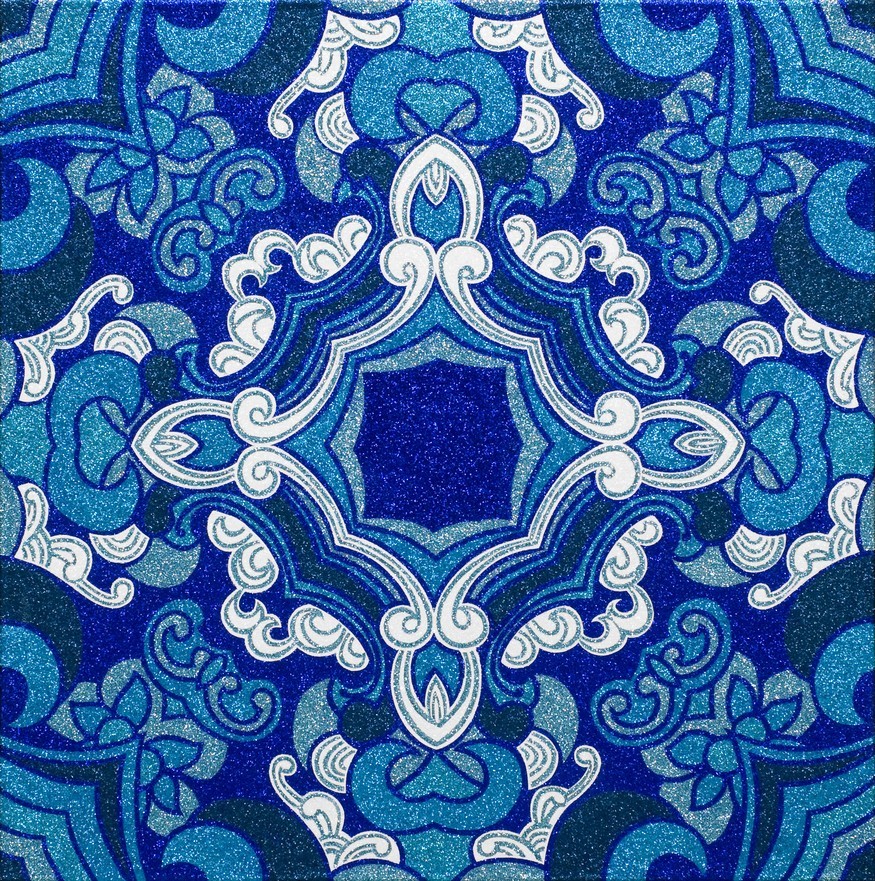

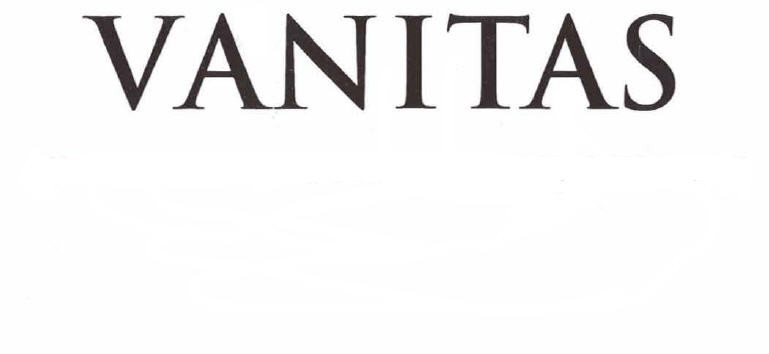

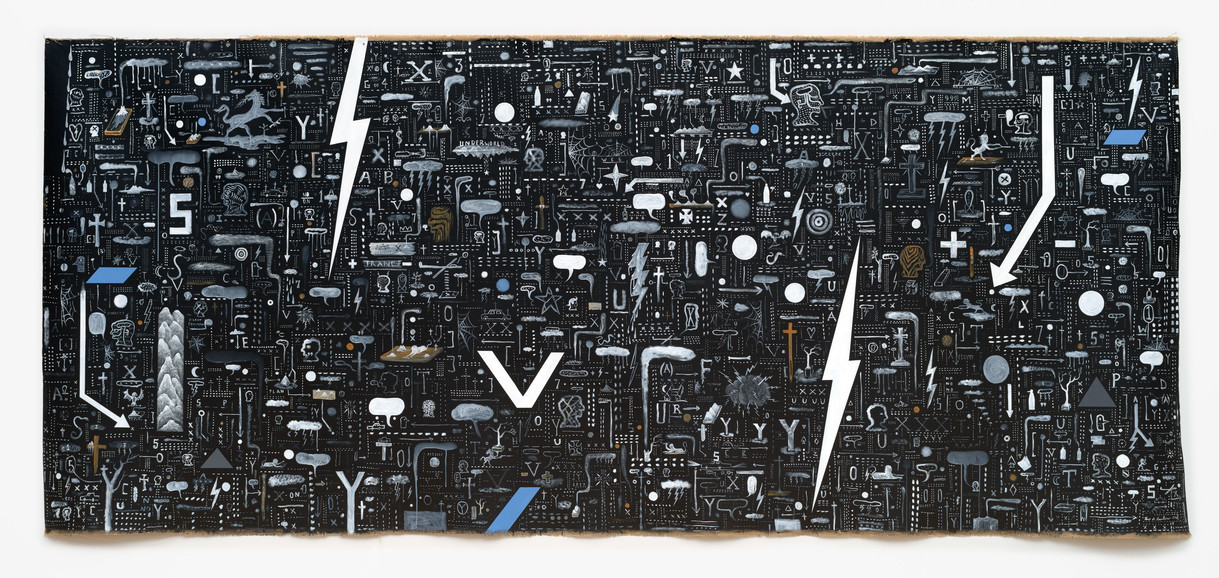

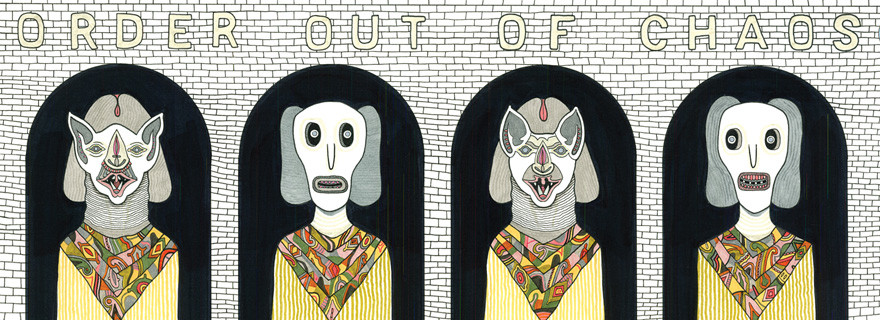

Tony de Lautour Untitled 2012. Acrylic on board in found frame. Reproduced courtesy of the artist and Brooke Gifford Gallery

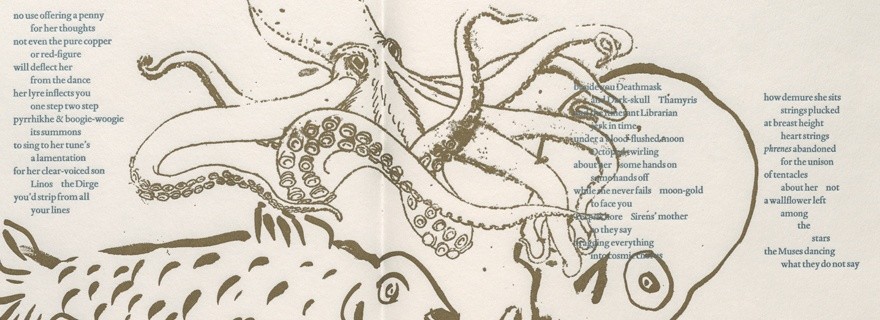

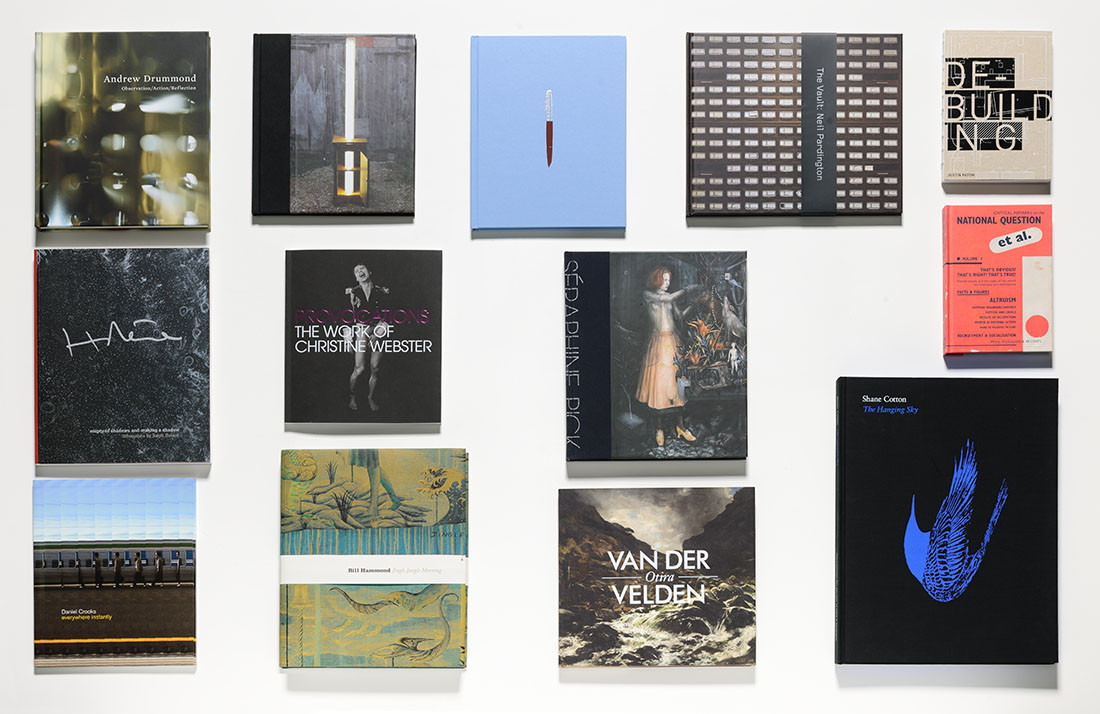

A miscellany of observable illustrations

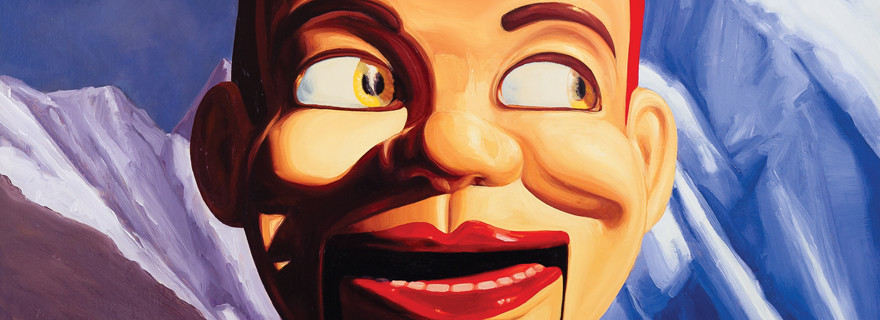

Romantic notions of gothic leanings, the legacy of Tony Fomison, devotion to rock sub-genres and an eye to the past are familiar and sound reasons to group Tony de Lautour, Jason Greig and Bill Hammond together in one exhibition, but De Lautour / Greig / Hammond is to feature new and recent work. Could all this change? What nuances will be developed or abandoned? Will rich veins be further mined? We can only speculate and accept that even the artists concerned can't answer these questions. For the artist, every work is a new endeavour, a new beginning. What may appear to the public, the critic or the art historian as a smooth, seamless flow of images is for them an unpredictable process where the only boundaries are those that they choose to invent.

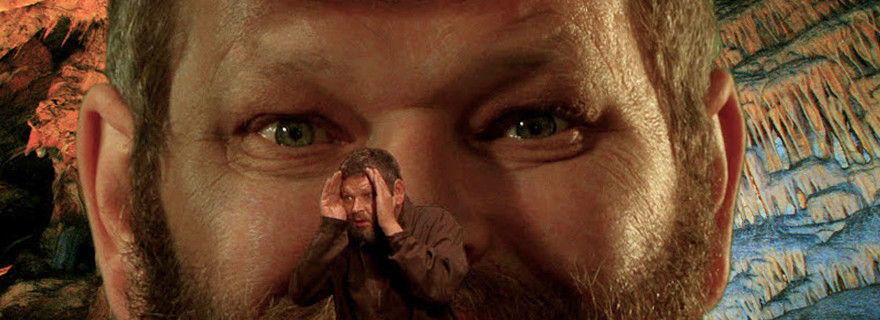

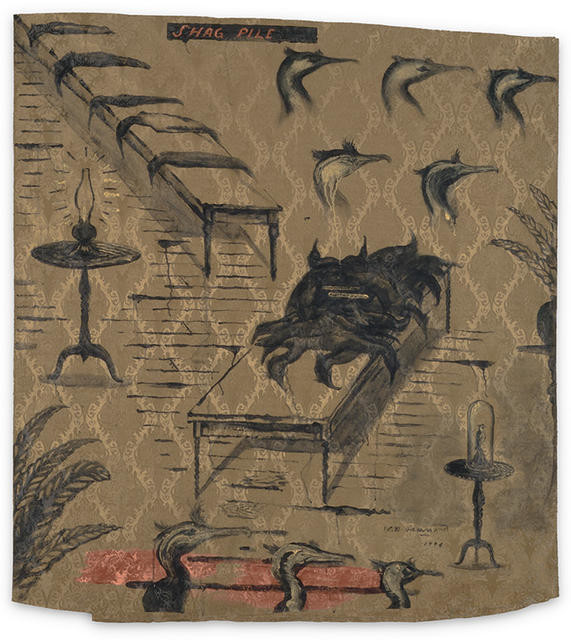

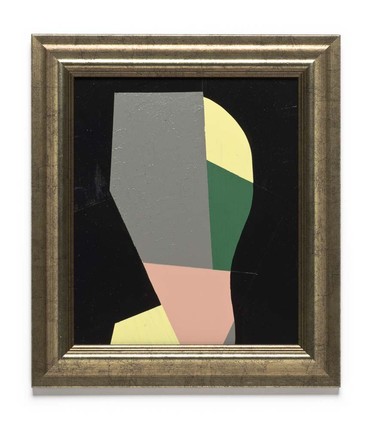

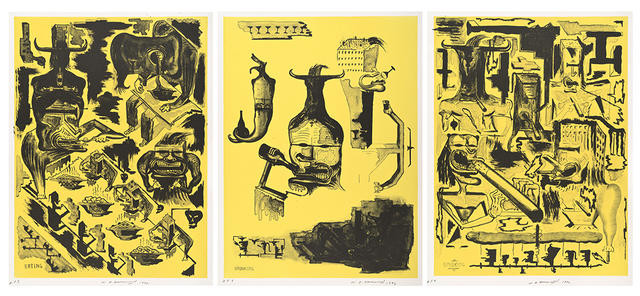

In recent years a strong shift has been readily observable in the work of Tony de Lautour. Left to history, or at least temporarily sidelined, are the cobwebs, the smoking heads, the punk kiwis and other Ed Roth Rat Fink analogies. Figurative elements have all but disappeared from his paintings, to be replaced by modernist blocks of solid colour in pastel pinks and blues. At first these simple shapes mimicked letter forms, the words they created hidden in the abstraction. More recently, similar shapes have served as elements to construct reductive forms reminiscent of the early twentieth-century abstract paintings of the Suprematists and Vorticists. Seeking to extend cubism, the Vorticists took up the modernist dictum of poet Ezra Pound to 'Make it new!' While De Lautour also strives to make it new he chooses to do so by making it old.

De Lautour has always shown a penchant for the aged. Whether it's the surface incidence of impasto and faux wood-grain or using old paintings, found pieces of wood, vintage saws or the pages of real estate publications to paint on, he often attempts, in some manner, to disrupt and interfere with the reception of the applied image. The flat painted geometric shapes that currently hold and accentuate the surface in his work are no exception, and the ground of the paintings as well as the modernist enterprise continue to be corrupted by his grunge aesthetic. Painted shapes are superimposed on spray-can backgrounds or, imitating both the aging of old master paintings and the art of the forger, a faux craquelure. Accented by cool blacks, the colour palette consists of kitchen-cupboard pastels sourced from leftover tins of stodgy paint gleaned from garage sales. Amid these interventions and self-conscious dribbles of paint the machined utopian imaginings of the early modernist mentality segue into a more immediate contemporary urgency.

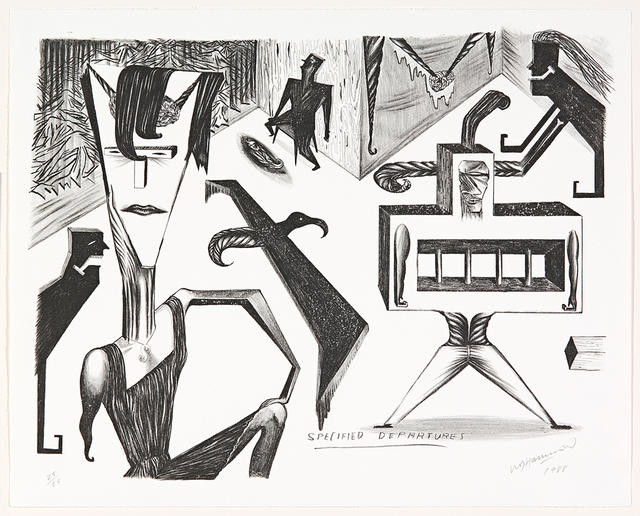

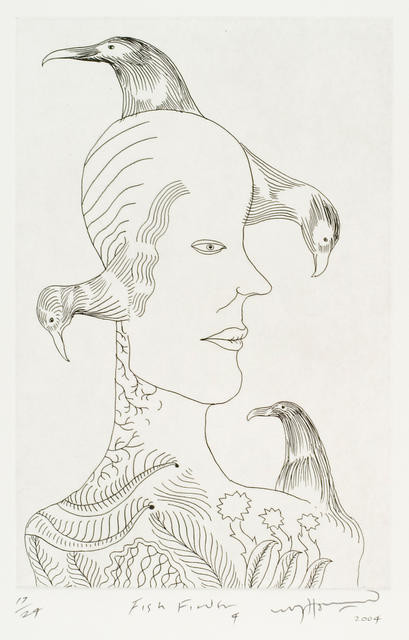

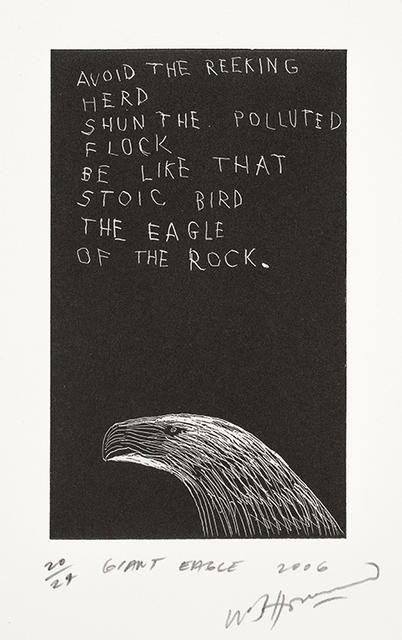

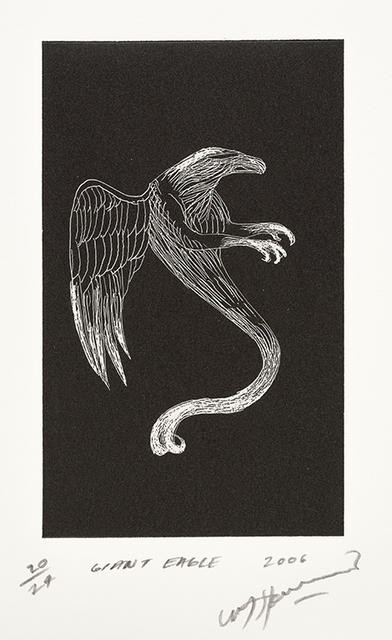

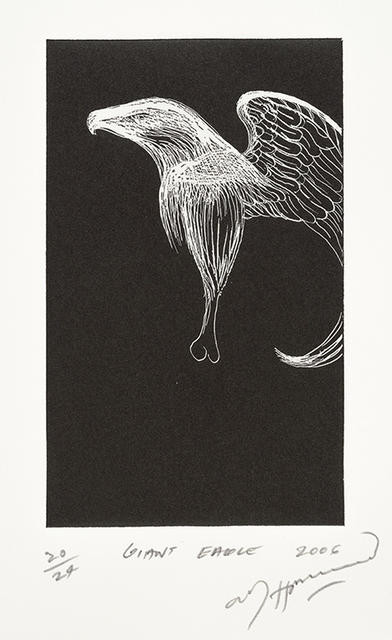

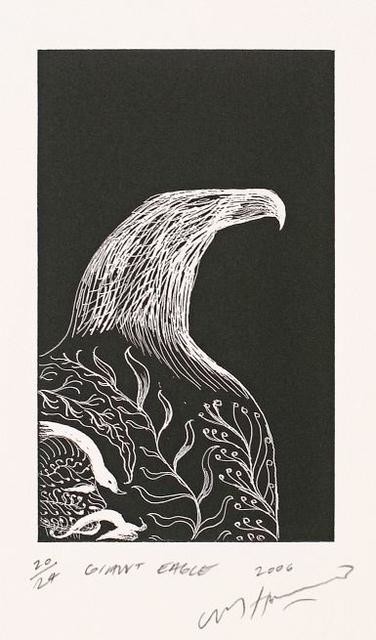

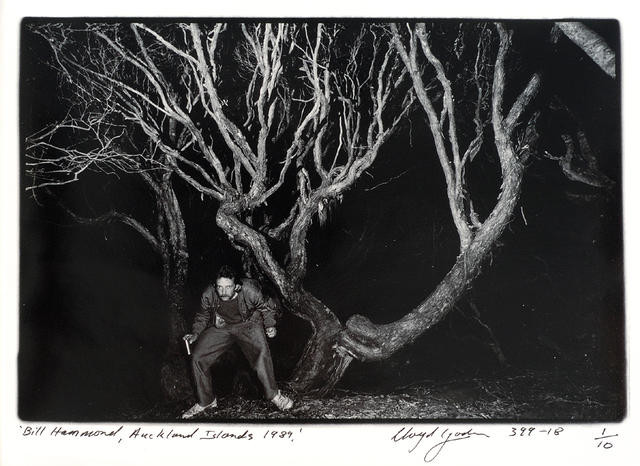

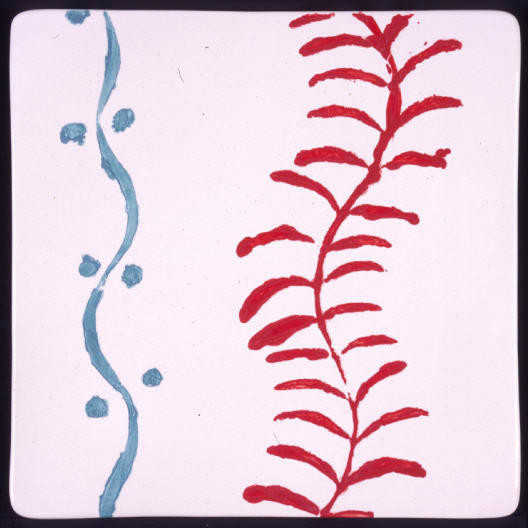

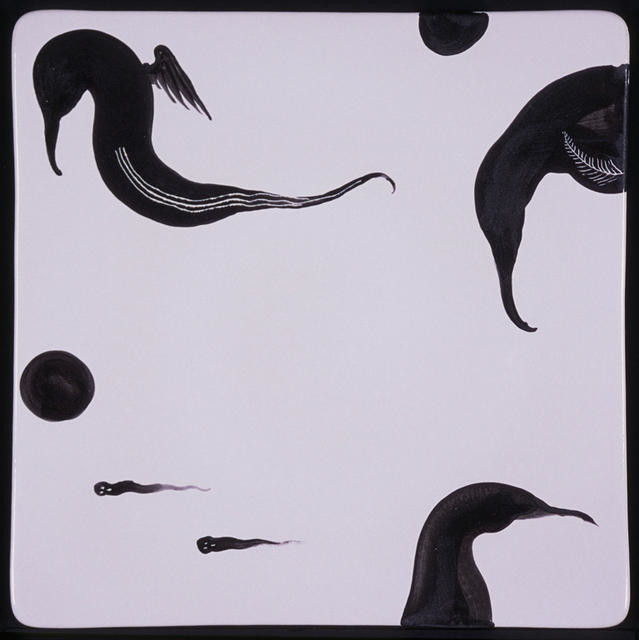

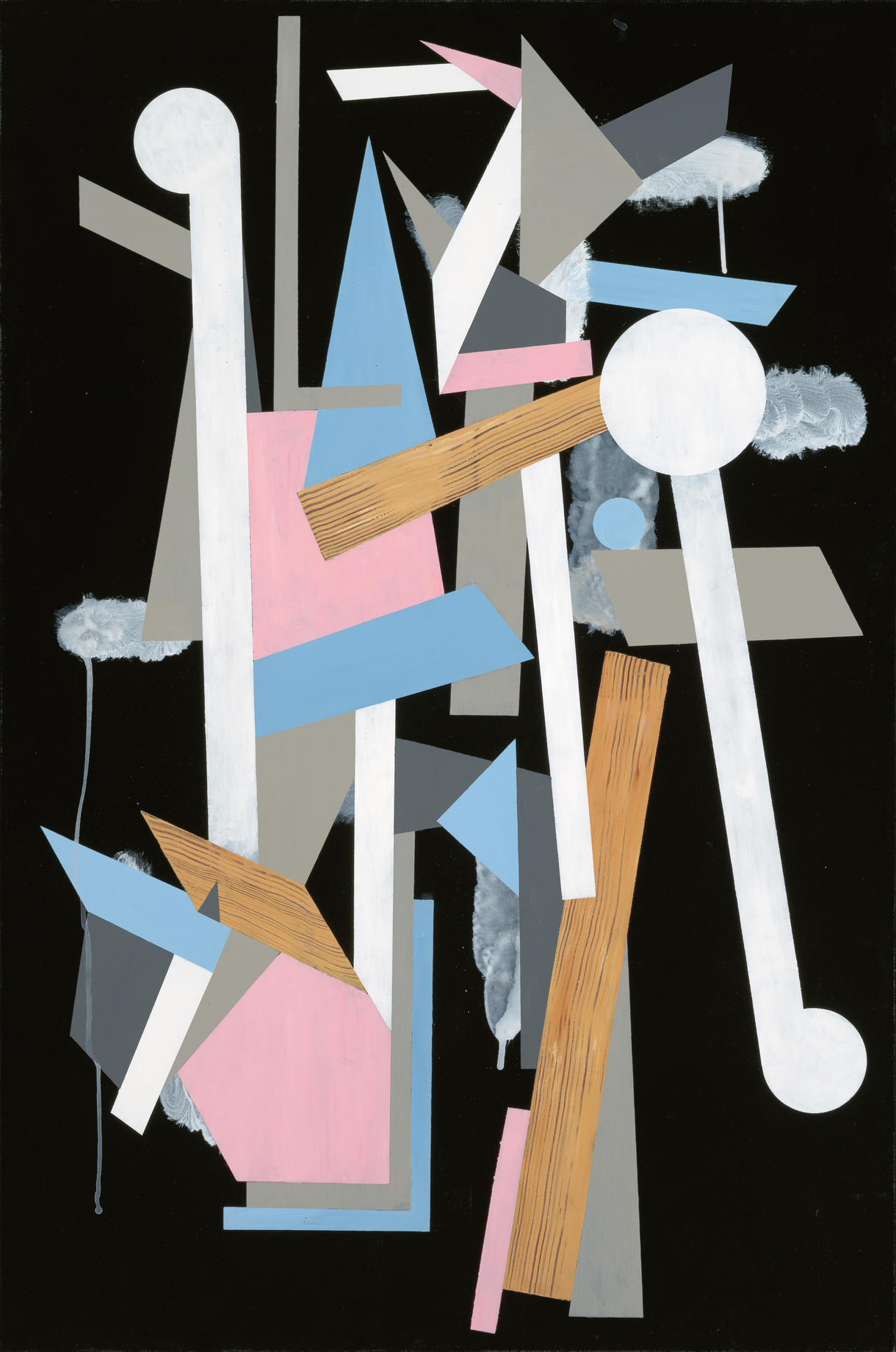

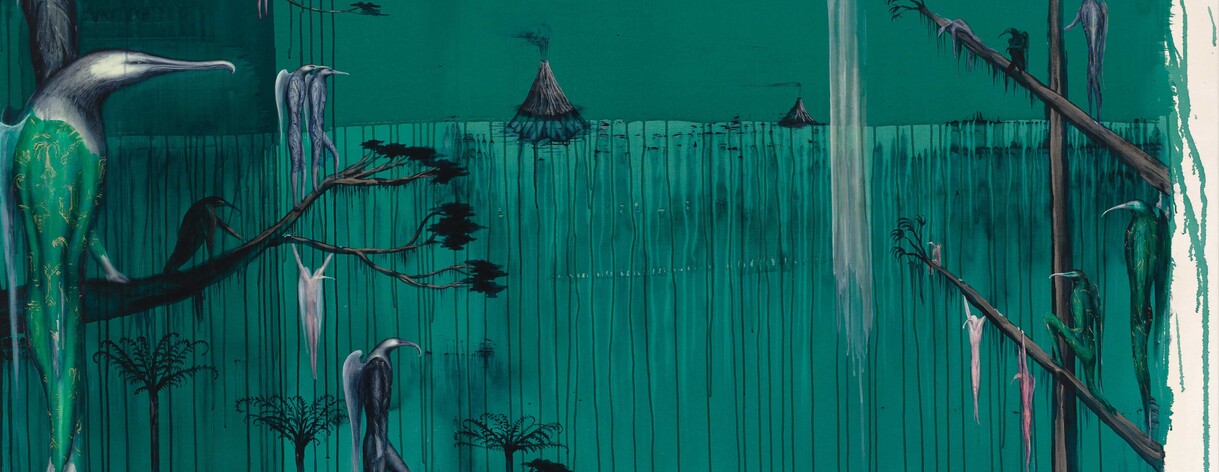

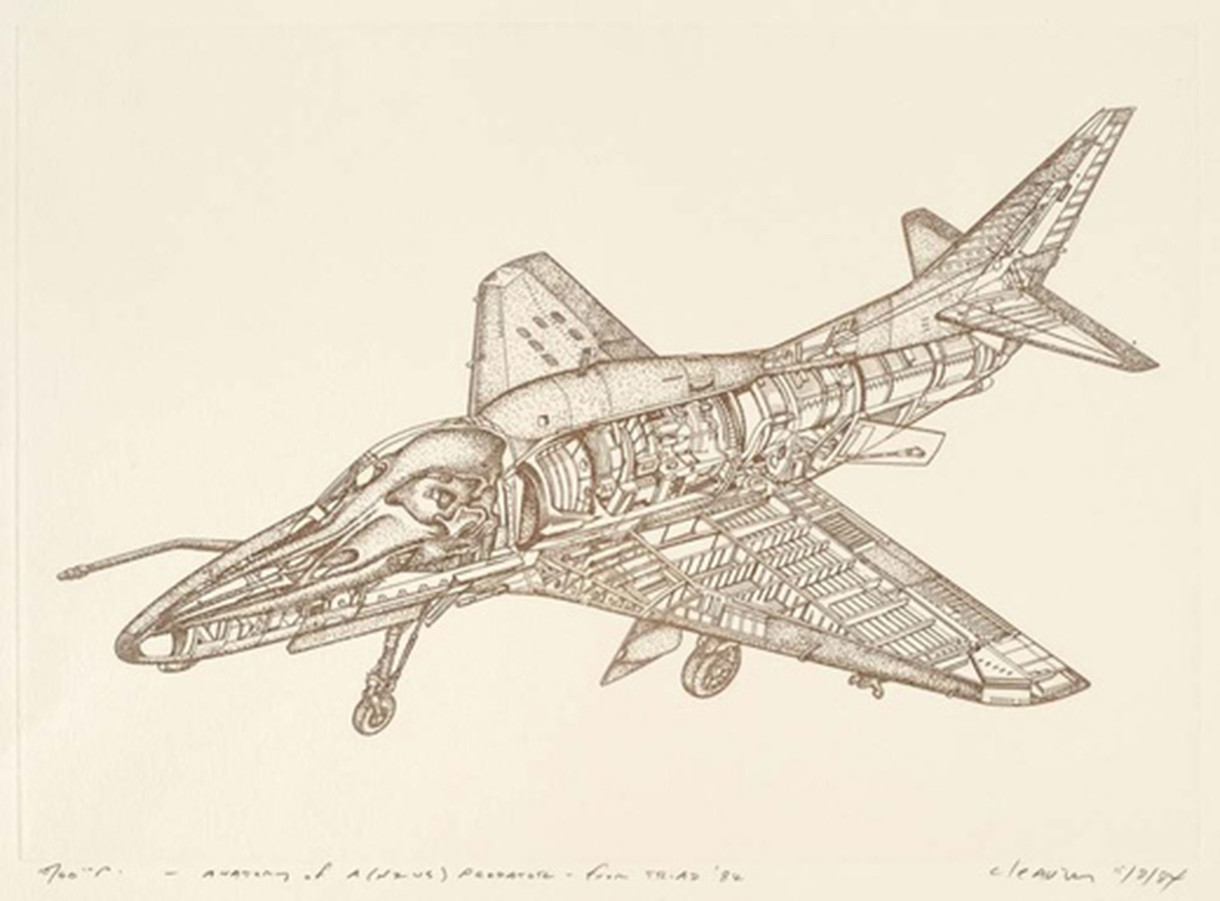

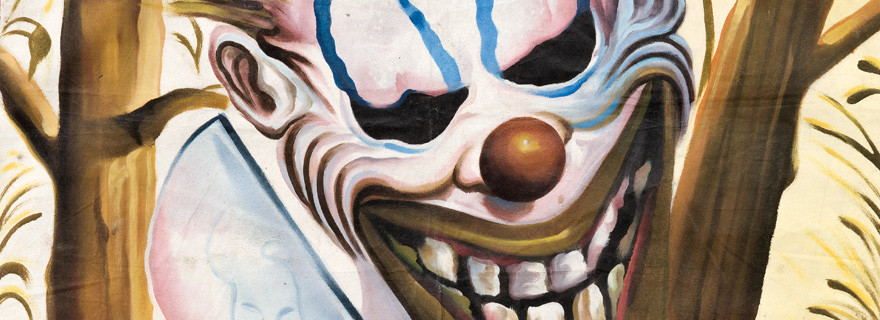

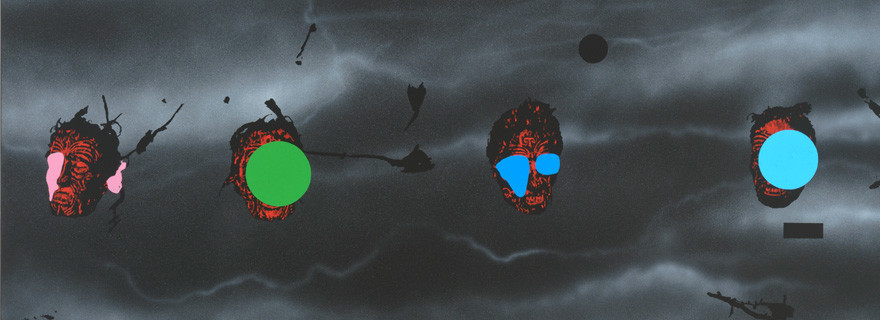

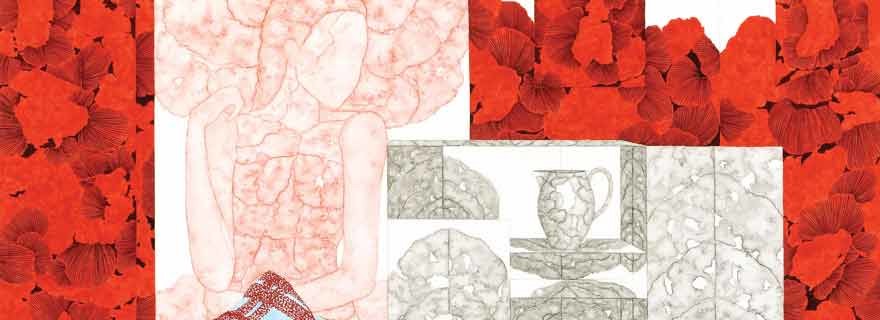

Bill Hammond Proto 4 2012. Lithograph. Reproduced courtesy of the artist and Papergraphica

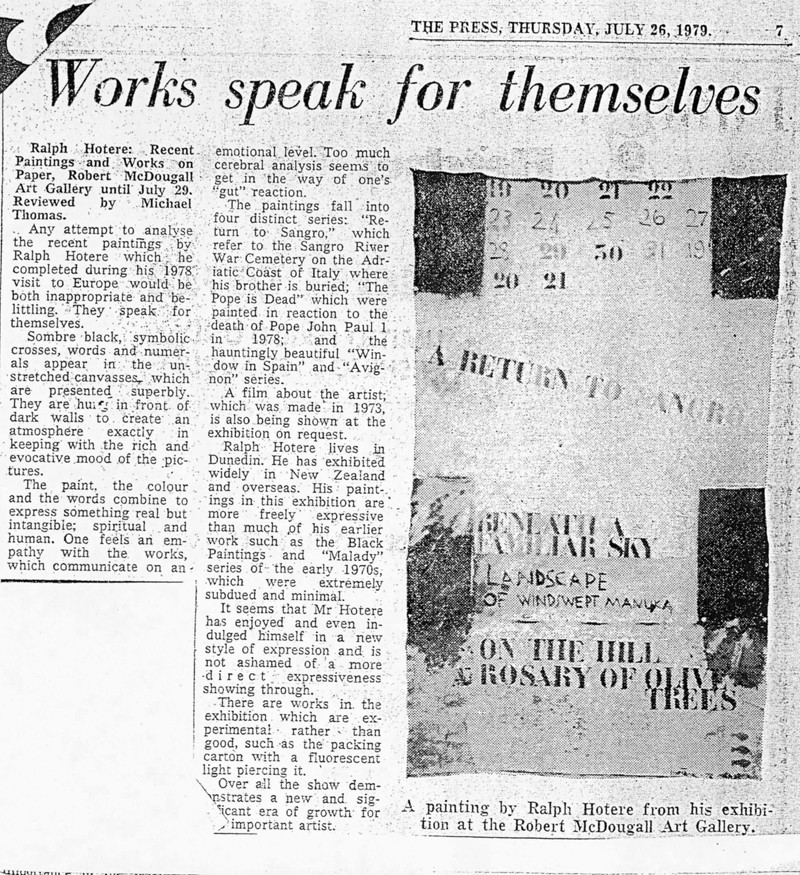

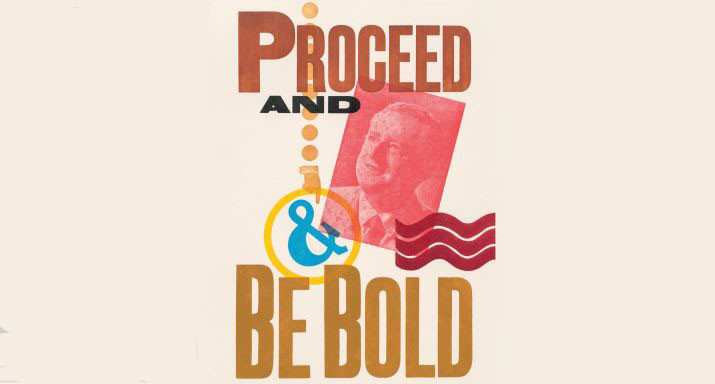

If the past in Bill Hammond's paintings is anything to go by, the characters who inhabit it rarely stray far from their natural habitat. They are never hurried. They may occasionally visit a local pool hall, play a musical instrument or pose for a portrait, but as often as not they seem content to wait for something to turn up – even at times to the extent of taking on the appearance of wallpaper with intricate all-over decorative patterning. They rarely attempt full flight and are happy to hover or float about in an apparently weightless atmosphere. It's the quiet illusion of an extended moment where the only sound is a ticking clock; change is slow and subtle.

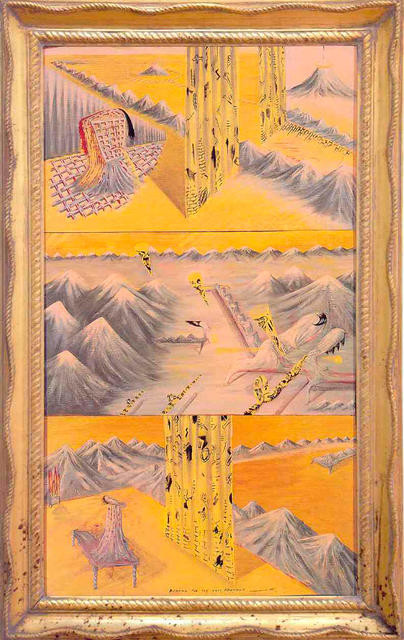

Long gone, it would seem, are the angst-ridden blockheads and zigzag-limbed antagonists of the early years. The sleek-bodied bird people that overtook them were long content to contemplate from treetops and shorelines a paradise lost, whereas more recently Hammond's paintings have begun to suggest a paradise regained. The inhabitants of his willow-pattern-land have discreetly grown more defined wings and become reminiscent of the angels in a Gustav Doré biblical engraving. The monochromatic green mist has been known to lift, revealing scenes tinged with a golden glow or the full colour of daylight, complete with cloud-dappled blue skies. The only lingering sombre note in Hammond's recent soundless song of summer has been the emergence of cinerary urns, and even these funereal echoes have been suitably decorated as if to distract from their contents. Along with dissolving plumes of smoke and images of a wishbone, the urns imply mortality and the hope that the breaking bone is favourable and the wish to savour each passing moment is granted. For who knows what tomorrow may bring.

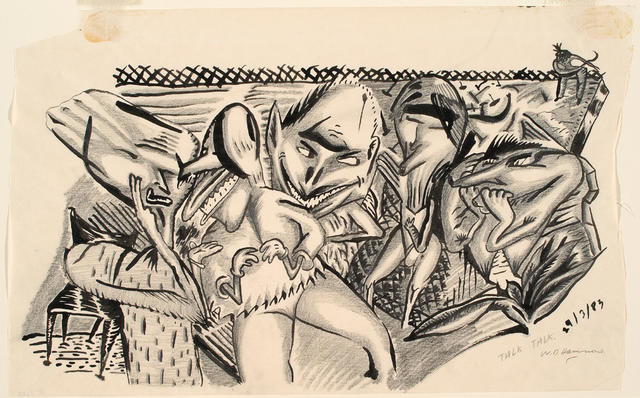

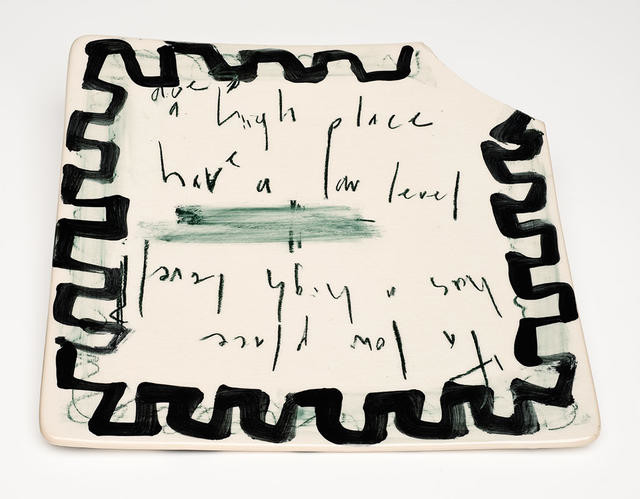

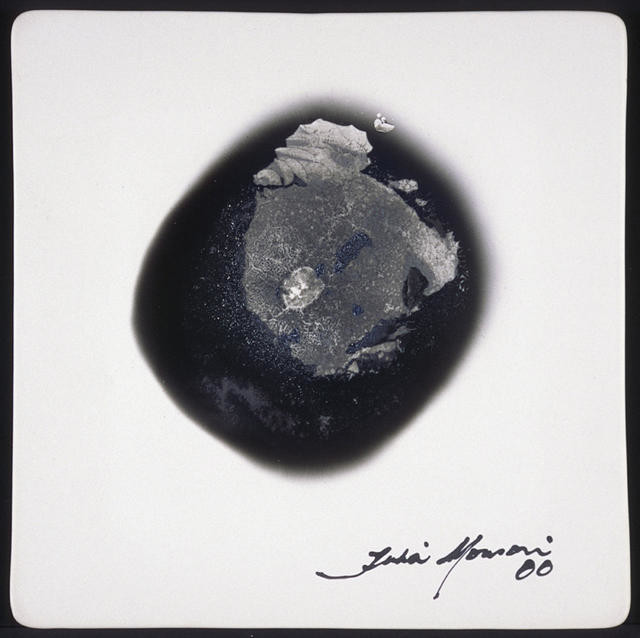

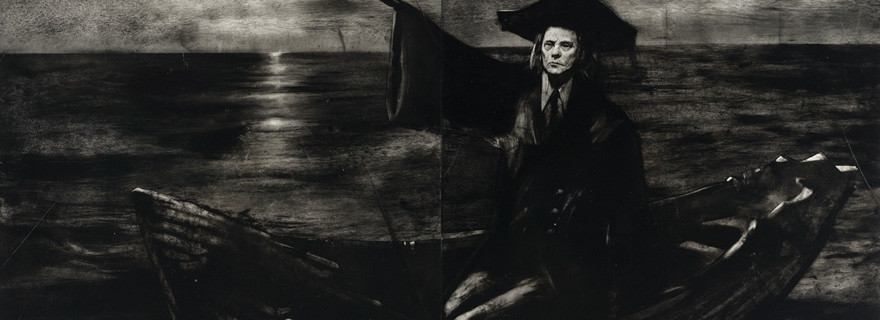

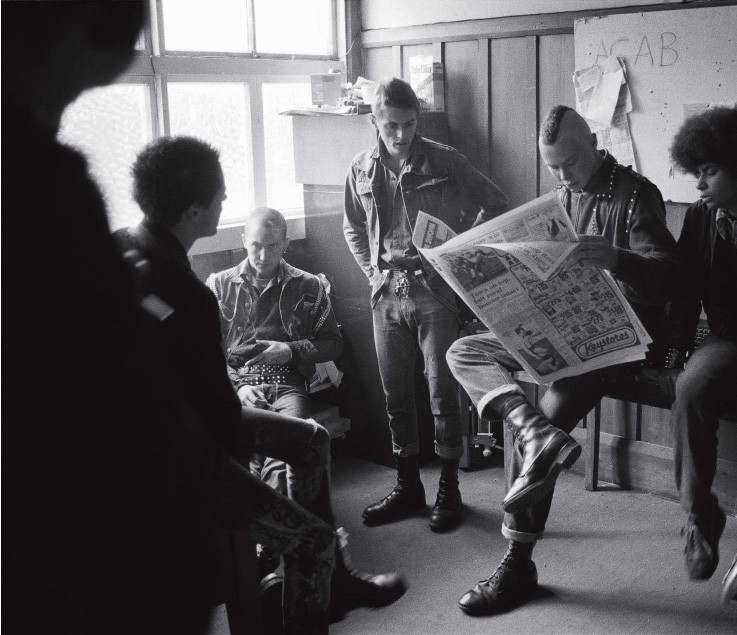

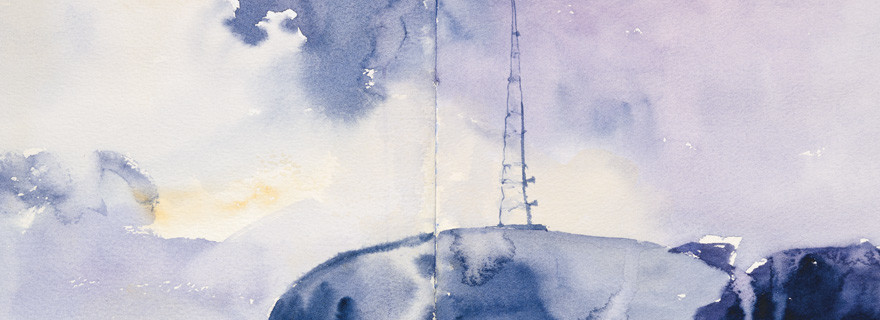

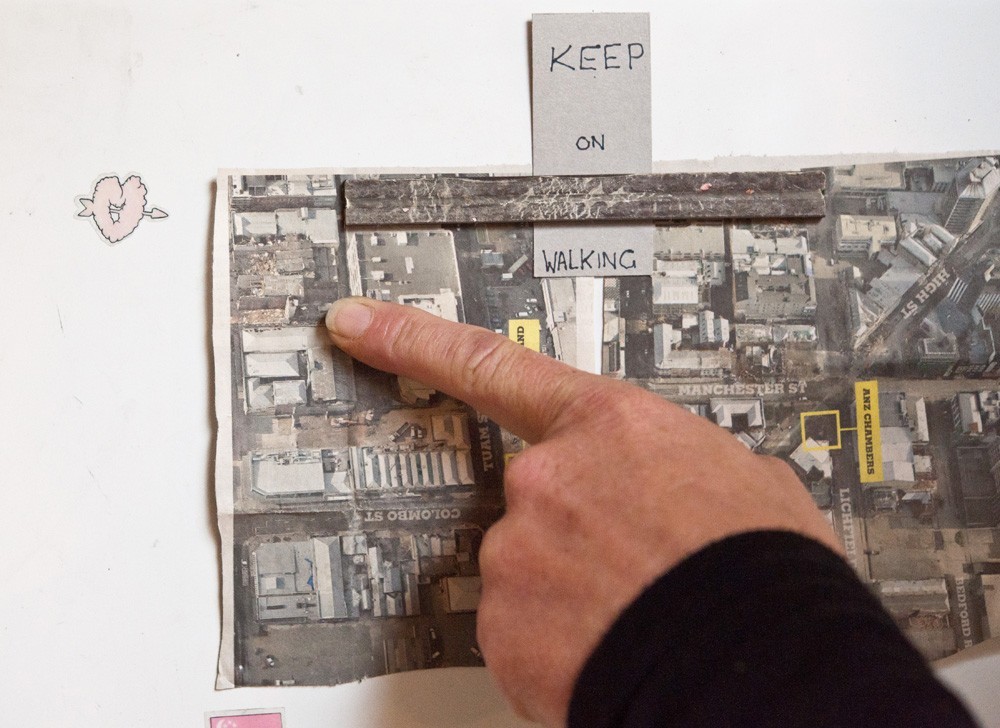

Jason Greig Farewell Italica... say goodnight Gracie 2012. Monoprint. Reproduced

courtesy of the artist and Hamish McKay Gallery

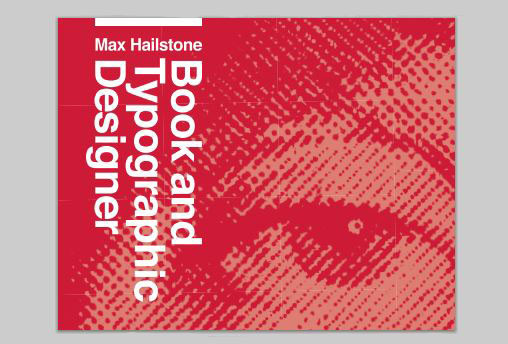

Jason Greig's working method lends itself readily to the capture or cornering of shifting moods and odd thoughts. Coupled with the monoprint process, the stencil-like forms he uses to create his images act as templates that can be reworked and recycled into subtle variations on drifting themes. Like an Antipodean Edvard Munch, he visits his subjects over and over again. Greig's gallery of images can be rearranged at a whim and cast in a different light, like Giorgio Morandi's bottles, bowls and vases, or James Ensor's carnival masks and skeletons. With a simple straightening of a tie, the tilt of a hat, a touch of make-up here or there and a pat on the back, Greig ushers his players back into his carnival of souls to await their fate. Drawn from a repertoire similar to that of the silent screen actor Lon Chaney – the Man of a Thousand Faces, famous for his portrayals of such grotesques as the Hunchback of Notre Dame and the Phantom of the Opera – the faces that stare back at us from Greig's macabre melodramas are equally afflicted.

Yet of late some of Greig's images have begun to leave their claustrophobic chiaroscuro. He seems to have managed to drag himself away from Miss Havisham's wedding table, brush away the cobwebs, dust himself down and head for the door. Forms and figures have become more fully formed, perhaps even defiant, taking on a more direct poster-like appearance, with strongly defined edges, crushed blacks and saturated colour: rich reds, radiant violets and velvet greens. The shadowy figures that lurked in Greig's Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde visions appear to have been sedated and deposited in a sealed crypt. It would be unwise, however, to assign his characters to the literary past from which they may have emerged for, with Greig, we must always be prepared for the unexpected hand on the shoulder or the gruesome result of a premature burial.

---------------------------------------------------

On some level an artist's work is always a surrogate or subliminal self-portrait and when the artist's thoughts change or mood shifts usually the work follows. The colour fades or heightens, the tones darken or lighten, the focus blurs or becomes more acute – for it is seldom the subject an artist depicts that forms the image and imparts its resonance but how it is made.

Robin Neate is an artist and writer and is currently a lecturer in painting at the University of Canterbury's School of Fine Arts. De Lautour / Greig / Hammond was on display at the NG space on Madras Street from 2 February until 10 March 2013.

![Brian Crook: Anti-Clockwise Bride of the elevator [10:39] 2009](/media/cache/04/26/0426f04983adfe4d58c15bf0b50c47c3.jpg)

![Adam Willetts: Star Canyon 10.5.2010 [5:00 mins]](/media/cache/ce/fb/cefbe4b1f2f04e9000de04325214300c.jpg)