B.

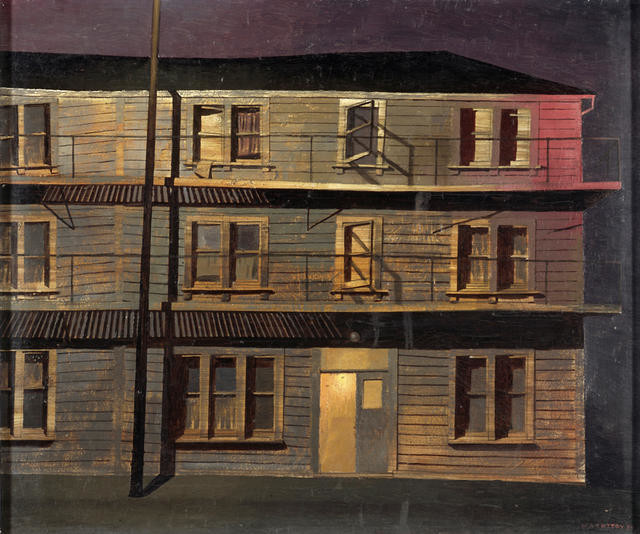

Yertle the Turtle by Glen Hayward

Collection

This article first appeared in The Press as 'An Ode to Yertle the Turtle' on 13 May 2015.

On encountering Glen Hayward’s towering Yertle sculpture, you could be forgiven for thinking that the artist, short on time and inspiration, had simply raided Christchurch Art Gallery’s cupboards for a bunch of old paint tins and stacked them up loosely in a teetering, telescoping tower. Hmph, you might say – perhaps as you eased past gingerly – couldn’t anyone do that? It’s true that Hayward drew directly from the Gallery’s leftovers for inspiration, after coming across a stash of half-empty pots in a back-of-house store, but his work is not such a ‘readymade’ as it first appears. Those curious enough to examine the materials list will find that the 28 cans that made it into the exhibition space are in fact lovingly fashioned replicas, carved meticulously from kauri, pine, puriri, rimu and totara he salvaged from old fence posts and other discarded building materials around his Hokianga studio. Which makes another question suddenly seem more pertinent: why would he bother?

Auckland-born Hayward has built a career on art by stealth. Previous works have mimicked recycling bins, apple boxes, fire extinguishers, even surveillance cameras – not to mention his life-sized rendering of Mr Anderson’s office cubicle from The Matrix (displayed in Christchurch in 2013 as part of the Gallery’s Outer Spaces series). The elaborate care with which Hayward recreates his subjects in wood is not solely about deception; it’s also about monumentalising things that usually get overlooked. The beauty of polystyrene packaging, for example, is not something that typically stops us in the street, yet Hayward’s insistence on a longer look opens our eyes to its seductive potential as a visual object.

In the case of Yertle, it’s the recognition that these cast-off paint pots, destined for the industrial waste depot, actually offer an alternative, unauthorised record of the Gallery’s history, distinct from exhibition lists, curatorial commentaries and visitor numbers. Instead they silently catalogue how the Gallery evolves from show to show by altering the colours used on its walls: black for Bill Culbert’s luminous bottle-and-light sculpture Pacific Flotsam; a racy shade of burgundy for an exhibition titled The Naked and the Nude. Tins intended to contribute anonymously to the carefully choreographed ambience are singled out and propelled onto centre stage, their every detail replicated in native timber, down to the drips of paint around their rims and handwritten post-it-note labels. Like the growth rings of a venerable tree, Yertle illustrates the back-of-house method of measuring time; wall by wall, show by show. And then, of course, there’s the title – a reference to Dr Seuss’s famous turtle king who commanded his subjects to stack themselves beneath him so that he could see further and expand his kingdom. When creating this work for the Gallery’s short-lived De-Building exhibition, Hayward wasn’t to know that the 2011 earthquake would close the doors on it as abruptly as Yertle the Turtle was eventually propelled into the mud by the smallest turtle’s burp, but that knowledge will add another layer of meaning to the work when it rises again in the Gallery’s reopening show later this year. It’s nearly time to reset the paint-pot clock.