B.

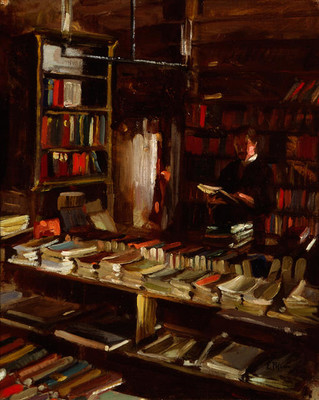

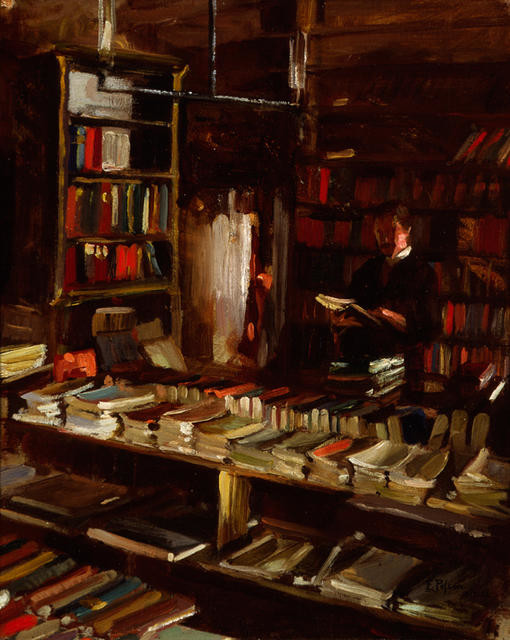

The Old Bookshop by Evelyn Page

Collection

This article first appeared as 'Page didn't start out wanting to be painter' in The Press on 20 January 2015.

Evelyn Page used to pass seven bookshops each day on her way to the School of Fine Arts from her family home in Sydenham. In 1922, the year that she left art school, she painted one of them. She recalled later in life: "I used to browse in an old bookshop—secondhand—smelling of musty books. I can remember starting the painting at art school—after that nothing at all!"

The shop Page painted may have been McCormack's secondhand bookshop on the corner of Hazeldean Road. Christchurch was full of bookshops in the 1920s. There was Whitcombe & Tombs in Cashel Street, which later became Whitcoulls; Halewood's in Hereford Street; Burtt's in Worcester Street, selling books for students; Smith's, established in 1894 and a Christchurch landmark ever since; and Simpson and Williams ('the bookshop that never disappoints!') at 238 High Street, among many others. Many bookshops sold both new and secondhand titles, and some also featured printing departments and public writing desks. Then, as now, bookshops were important meeting places and centres of culture for Christchurch people.

Contemporary international art publications were hard to find in Christchurch in the first half of the 20th century. Page remembered poring instead as a student over the annual publication of the Royal Academy and the London Studio magazine: "This was all one had in those days of news of painting overseas and it was pretty dreary stuff." Gradually, several of her friends went to study in Paris and brought back news of "strange new goings on"; they described works they had seen by Gauguin, Renoir, Van Gogh and Cézanne. The Old Bookshop is a transitional work, caught between the academic and the modern, in which the careful capturing of detail is combined with areas of radical simplification.

The Old Bookshop was painted before Page had decided to make her career as an artist. She had left art school a little jaundiced with the academic approach—'I'd had painting!' she later commented—and devoted herself to studying music for several years. While The Old Bookshop demonstrates the formal concern for the effects of light and shade on objects which was part of her art school training, in its vigorous brushwork and elements of pure colour it anticipates the gestural works for which she later became known.

In the 1920s New Zealand art was dominated by regional art societies which controlled the accepted standards of taste. Although initially ambivalent about making a life as an artist, Page was elected as a working member of the Canterbury Society of Arts early in the year that she finished painting The Old Bookshop. The work was displayed in Christchurch, Dunedin and Auckland at the annual art society exhibitions, and set Page on the circuit as a professional artist. However, the conservative nature of the art society was not to Page's liking; she was a founding member of The Group in 1927, a breakaway association of younger artists who exhibited together and fostered new talent. Page remembered it as "a social club for young painters who wanted to find somewhere to meet away from their Victorian parents."

Page's Old Bookshop is a significant local work from the early 1920s; but the bookshop itself appears almost timeless. Without the overhead gas fittings, it could have been painted at almost any time during the 20th century, in Smith's, or John Summers's bookshop, or Ringo's on Manchester Street. Page's work is instantly evocative of the dusty interiors of secondhand bookshops, those dark corners filled with antiquarian obscurities and hidden treasures. George Orwell, who worked in them in London in the 1930s, had a more dyspeptic view: "As a rule a bookshop is horribly cold in winter, because if it is too warm the windows get misted over, and a bookseller lives on his windows. And books give off more and nastier dust than any other class of objects yet invented, and the top of a book is the place where every bluebottle prefers to die."